- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

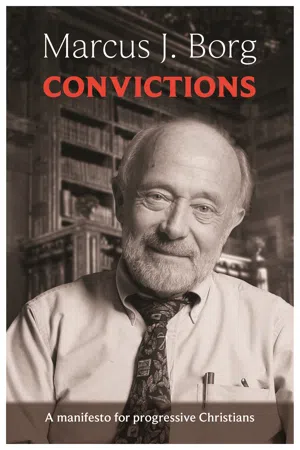

The story of my life and my Christian journey is about memories, conversions, and convictions. Memories of what I absorbed growing up. Conversions: major changes in my understanding of the Bible and God and Jesus and what it means to be Christian. Convictions: the affirmations that have flowed from those changes. Three kinds of conversions and convictions have shaped my life: intellectual, political and religious . . .' Marcus Borg 'Many know Marcus Borg as a brilliant scholar, which he is. But he has a pastoral side as well. I've stood with Marcus after his lectures and watched as person after person comes up to say, "I lost my faith, but your books have helped me get it back," or "I wouldn't be in the church today if I hadn't come across your books," or "Your work has helped me stay a Christian."' Brian McLaren

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Convictions by Marcus Borg,Marcus J. Borg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Context Matters

THE IDEA FOR THIS BOOK emerged in a particular context. It was born as I prepared a sermon for the Sunday of my seventieth birthday in what was then my home church, Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon.

My birthday was (as always) in Lent. One of that season’s central themes is mortality. It begins on Ash Wednesday with a memento mori—a vivid reminder that we are all mortal and marked for death. Ashes are put on our foreheads in the shape of a cross as we hear the words, “Dust thou art, and to dust thou wilt return.” None of us gets out of here alive.

Seventy may be the “new sixty,” but it is not young. Mortality looms large. In one of John Updike’s last novels, the main character reflects as he turns seventy that half of American men who live to age seventy do not live to eighty. Soldiers in combat have a better chance of survival, even in the trenches of World War I or in the killing fields of the German-Russian front during World War II.

I have lived the three score and ten years that the Bible speaks of as a good span of life: “The days of our life are seventy years / or perhaps eighty, if we are strong” (Ps. 90.10). Then, like Ash Wednesday, the passage continues with a memento mori: “They are soon gone, and we fly away. … So teach us to count our days / that we may gain a wise heart” (90.12).

But despite the unmistakable onset of serious aging, turning seventy has not been grim. Turning sixty was much more difficult. It felt old. Nothing in my childhood had prepared me to think of sixty as anything other than that. Sixty felt like the end of potential and the beginning of inevitable and inexorable decline.

At seventy I primarily feel gratitude. Each extra day feels like lagniappe, a Cajun French word that means “something extra”—like the cherry on top of the whipped cream on top of the hot fudge on top of the ice cream. I enjoy my days more than I ever have. At seventy, life is too short to spend even an hour feeling preoccupied or grumpy or out of sorts.

I have also experienced a second and unexpected effect of turning seventy: it has been interestingly empowering. In a sentence: If we aren’t going to talk about our convictions—what we have learned about life that matters most—at seventy, then when? Some care needs to be exercised. Seventy isn’t a guarantee of wisdom or a license to be dogmatic. It’s quite easy to be an opinionated old fool.

The process of preparing that sermon led me to the triad that shapes this book: memories, conversions, and convictions. Memories: especially of childhood but also of the decades since. Conversions: major changes in my orientations toward life, including how I understand what it means to be Christian. Convictions: how I see things now—foundational ways of seeing things that are not easily shaken. Whether we are conscious of it or not, I think the triad of memories, conversions, and convictions shapes all of our lives.

When I mentioned to a friend that I was working on this book, he asked, “So you’re writing a memoir?” His question caused me to think about whether I was. “No,” I said, “not a memoir in the sense of an autobiography.”

As autobiography, my life in many ways has been unremarkable, except in the general sense that all of our lives are remarkable. Most of it has been spent in educational settings, from kindergarten through graduate school and then more than four decades as a teacher in colleges, universities, seminaries, and churches, and continuing in my life “on the road” as a guest lecturer. In the past few years before retiring from university teaching, I sometimes remarked to my students, “I’ve been in school since I was five.”

So, there’s nothing remarkable about my life, nothing heroic. And yet this book is a bit of a memoir. Most chapters include memories, conversions, and convictions. In that sense, this book is personal.

It is also more than personal, more than my story. Many people in my generation (and some in younger generations) have similar stories. Most Americans over a certain age share the experience of growing up Christian. Many of us have experienced a loss of our childhood faith because of conflict between what we learned as children and what we learned later, not just in school and college, but from life. Adult consciousness is quite different from childhood consciousness.

My Cultural Context: American Christianity

For another reason this book is more than personal. It is also about being Christian and American. I have been both all of my life, even while living overseas for about six years. Together, being Christian and American provides the culture and ethos that have shaped me and that I know most intimately. It is also the cultural context of most people who will read this book.

American Christianity today is deeply divided, and its divisions have shaped my life and vocation and convictions. I have changed through a series of conversions from being a conventional and conservative Christian to the kind of Christian I am today.

Of course, divisions within Christianity are nothing new. They go back to the first century and the New Testament. Christianity began as a movement within Judaism, and soon after Jesus’s historical life, it expanded to include Gentiles (non-Jews) as well. Thus a major issue arose: Did Gentiles who became followers of Jesus need to follow the Jewish law, including circumcision and Jewish food laws?

Some of the Jewish followers of Jesus said, “Of course.” Other Jewish followers of Jesus, including especially Paul, passionately opposed them and proclaimed that requiring circumcision and kosher food practice for Gentile converts was a betrayal and abandonment of the gospel.

By the beginning of the second century, there were Christians who maintained the radical vision of Jesus and the seven genuine letters of Paul, and Christians who accommodated that vision to the conventions of dominant culture, including especially patriarchy and slavery.

Also in the second century, there were gnostic Christians who denied the importance of this world. For them, Christianity was primarily spiritual. It was not about the transformation of this world, but primarily about rising above it into a different world, the world of spirit.

Their Christian opponents strongly affirmed that the world is the creation of God and matters to God. The latter won and became orthodox Christianity—though the conflict between these positions is still with us. Does the world matter to God or not? The history of Christianity ever since is pervasively ambiguous.

Divisions continued as Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries. The Roman emperor Constantine (born in 272 and died in 337) and most of his imperial successors wanted a unified Christianity for the sake of a unified empire, so they sponsored councils of bishops to resolve disputes among Christians. The most important were in 325 at Nicea and in 451 at Chalcedon, both in Asia Minor (modern Turkey). The result was “official,” or “orthodox,” Christianity.

But forms of Christianity continued that rejected the conclusions of the councils. They were condemned and often persecuted by orthodox Christians (not meaning today’s “Eastern Orthodox” Christians). Ironically, the quest for Christian unity produced the first officially sanctioned Christian violence against other Christians.

More division: almost a thousand years ago, in 1054, Western and Eastern Christianity divided in what is commonly called “the Great Schism.” It produced the Roman Catholic Church, centered in Rome, and the Eastern Orthodox Church, centered in Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Each excommunicated the other. The division became brutal and murderous: in 1204, Western Christian crusaders conquered and sacked Christian Constantinople in an orgy of violence and pillage that greatly exceeded the Muslim conquest of the city in 1453.

And more: in the 1500s, Western Christianity divided. The Protestant Reformation not only cleaved the Western church into Catholics and Protestants, but over time splintered into a multitude of Protestant groups: Lutherans, Anglicans (Episcopalians), Presbyterians, Mennonites, Baptists, Congregationalists, Quakers, Methodists, Disciples of Christ, and many more. I have heard that by 1900, there were about thirty thousand Protestant denominations. I have not checked this number out, but even if it is hyperbolic, it is true hyperbole.

I grew up in the world of denominational division half a century ago. The great divide was between Catholics and Protestants. In my Lutheran and Protestant context, we were deeply skeptical about whether Catholics were really Christians. When John F. Kennedy ran for president in 1960, a major issue was the fact that he was Catholic. Could a Protestant vote for a Catholic president?

The issue was not only political, but local and personal—and eternal. We Lutherans—at least the Lutherans I knew—were quite sure that Catholics couldn’t be saved. We saw their version of Christianity as deeply distorted: they worshipped Mary and saints and statues; they believed in salvation by good works rather than by grace through faith. “Reformation Sunday,” one of our festive Sundays of the year, was an anti-Catholic festival: it remembered and celebrated our liberation from the Catholic Church. They were wrong; we were right.

This division affected social relationships. I cannot recall that my parents had any Catholic friends. They (and pretty much everybody we knew) discouraged my dating a Catholic or even having close friends who were Catholic. It was unthinkable to marry one—though my oldest sister did. To a lesser degree, it was best not to date Protestants from other denominations. We knew that being Lutheran was best, and so it was good to confine mate selection to Lutherans.

Today’s Divisions

The divisions in American Christianity today are very different. They are not primarily denominational. Differences between the old mainline Protestant denominations no longer matter very much. Many have entered into cooperative agreements, including mutual recognition and placement of clergy. And among mainline Protestants, the old anathema toward Catholics is largely gone. It’s been decades since I have heard parents from a mainline Protestant denomination worry that one of their children might marry somebody from a different Protestant denomination or, for that matter, a Catholic.

Naming today’s divisions involves using labels. I recognize that labels risk becoming stereotypes and caricatures; indeed, the difference between “label” and “libel” is a single letter. Yet they can be useful and even necessary shorthand for naming differences.

Aware of this danger, I suggest five categories for naming the divisions in American Christianity today: conservative, conventional, uncertain, former, and progressive Christians. In somewhat different forms, these kinds of Christians are found among both Protestants and Catholics. And there are good people in all of the categories; none of them has a monopoly on goodness.

The categories are not watertight compartments. It is possible to be a conservative conventional Christian, a conventional uncertain Christian, a conventional former Christian, and so forth. But two categories strike me as antithetical and incompatible. The great divide is between conservative and progressive Christianity, which form opposite ends of the spectrum of American Christianity today.

Conservative Christians

The conservative Christian category includes fundamentalist Christians, most conservative-evangelical Christians, and some mainline Protestant and Catholic Christians. Most of us over a certain age, Protestant or Catholic, grew up with a form of what I am calling “conservative Christianity.” Today’s conservative Christians insist upon it. Its foundations are:

- Belief in the absolute authority of divine revelation. For conservative Protestants, divine authority comes from the Bible, which they understand to be the infallible, literal, and absolute Word of God. For conservative Catholics, divine authority is grounded in the teaching of the church hierarchy, with its apex in papal infallibility.

- Emphasis upon an afterlife. How we live now—what we believe and how we behave—matters because where we will spend eternity is at stake. For conservative Protestants, the possibilities are heaven and hell. Conservative Catholics continue to add a third possibility: purgatory—a postmortem state of purification for those neither wicked enough to go to hell nor worthy enough to go to heaven.

- Sin is the central issue in our life with God, the obstacle to going to heaven. Thus our great need is forgiveness.

- Jesus died to pay for our sins so that we can be forgiven. Because he was the Son of God, he was without sin and thus could make the perfect sacrifice for our sins.

- The way to eternal life (understood to mean “heaven”) is through believing in Jesus and his saving death.

Most conservative Christians also believe that Jesus and Christianity are “the only way.” Conservative Catholics commonly affirm a church doctrine known as extra Ecclesiam nulla salus—namely, outside of the church (the Catholic Church) there is no salvation. Though conservative Protestants reject the notion that the Catholic way is the only way, they do affirm that Jesus is the only way, and many assert that their particular way is the only or at least the best way.

Some conservative Christians would add to this list of beliefs. For example, believing that Jesus really was born of a virgin, that he did walk on water, that his physical body was raised from the dead, that he will come again in physical bodily form, and so forth. But I would be surprised if any would subtract from this list.

There are subdivisions within conservative Protestant Christianity. These include especially “the prosperity gospel” and “the second coming is soon gospel,” even as some conservative Christians resolutely reject both. The former proclaims that being Christian leads to a prosperous life here on earth. A blatant form is inscribed over the door of a mega-church with more than twenty thousand members: “The Word of God is the Way to Wealth.”

The latter emphasizes that Jesus is coming again soon for the final judgment and thus it is important to be ready. Books proclaiming this have been bestsellers for decades; forty years ago, we had Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and more recently the bestselling Left Behind novels by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins. How many Christians believe that the second coming and last judgment are at hand? The one relevant poll I have heard of suggests that 20 percent of American Christians are certain that Jesus will come again in the next fifty years and that another 20 percent think it is likely.

Conventional Christians

The category of conventional Christian refers to both the reason for being Christian and a particular content of what it means to be Christian. Reason or motive: many in my generation, and in generations before and some since, became involved in a church because of a cultural or familial expectation that they would be part of a church. Some of these people continue to participate in church life because of that convention. Some continue because they value Christian community, worship, commitment, and compassion.

Conventional Christians also share the understanding of Christianity affirmed in more passionate form by conservative Christians. Most learned it in childhood: namely, the Christian life is about believing in Jesus now for the sake of heaven later.

To a large extent, conventional Christians are “the Christian middle” in American Christianity today. They are not committed to biblical inerrancy and doctrinal insistence about correct beliefs as conservative Christians are. Yet they are not part of what I will soon describe as progressive Christianity. They may not even have heard of it.

Uncertain Christians

Uncertain Christians include many conventional Christians and some former conservative Christians. They have become unsure of what they make of conservative and conventional Christian teachings. Is the Bible really the direct revelation of God? Should it be interpreted literally? Was Jesus really born of a virgin? Did he really do all of the miracles narrated in the gospels? Did he really have to die to pay for our sins? Is Christianity really the only way of salvation? But despite such questions, these people continue to be part of a church, whether occasionally for reasons of convention or regularly for reasons of community. For some, belonging is more important than believing.

Former Christians

It may seem odd to include in a list of Christian categories those people who have left the church, but they are a large group. I have been told more than once that the largest “denomination” in the United States today is ex-Catholics. I do not know whether this is true, but there are many ex-Catholics. So also among Protestants. Mainline Protestant denominations have lost about 40 percent of their membership over the past half ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Imprint

- Dedication

- Table of contents

- Preface

- 1. Context Matters

- 2. Faith Is a Journey

- 3. God Is Real and Is a Mystery

- 4. Salvation Is More About This Life than an Afterlife

- 5. Jesus Is the Norm of the Bible

- 6. The Bible Can Be True Without Being Literally True

- 7. Jesus’s Death on the Cross Matters—But Not Because He Paid for Our Sins

- 8. The Bible Is Political

- 9. God Is Passionate About Justice and the Poor

- 10. Christians Are Called to Peace and Nonviolence

- 11. To Love God Is to Love Like God

- Notes

- Scripture Search Terms