1

Our story

Discovering and interpreting our identity

Our story is a very significant and precious thing. It is part of the way each of us shares with others who we are. It is part of our identity; it’s not just a tale told for amusement, it is part of us. Most of us are careful how we tell our stories, and much depends on who we are telling the story to. There are people we trust and love, and we are prepared to tell them things which we would not tell to someone we thought was untrustworthy, or who obviously disliked us. One of the first things to recognize about our stories is that they depend on the listener, the reader, as much as on the storyteller. Or, more accurately, they depend on the mutual relationship between the storyteller and the listener. When we tell someone something particularly personal about ourselves we are also telling that person that we have come to trust him or her.

The larger story will give people we trust an idea of our values and priorities, the kind of choices we make, the sort of things we do and the sort we are hardly likely to do, the kind of things that make us laugh and the kind that upset us or make us angry. It is an indicator of our practical wisdom, that peculiar bundle of habits and convictions which make us who we are.

There are always little stories within the larger story, and these are often illuminating. They can be typical stories, illustrating the sort of things we do:

Or they may be unexpected stories, revealing a different side of a person:

The really painful parts of an individual’s story are not told, though they are often guessed at:

A shared story, such as a family’s story, is also significant and precious, and in many ways it is like an individual’s story. It will be shaped and edited by the listener as well as the teller. The larger story will indicate values and assumptions. It might be said of one family, ‘They have always lived in Rotherham, wouldn’t dream of living anywhere else,’ while another family has members scattered round the world.

Within the family circle there may well be embarrassing stories about members which we treasure because they make us laugh, but these are not told to strangers. Or there are stories we do tell, but not if one particular person is present, because we know it upsets them.

Then there are the typical stories:

There are the unexpected:

And the ones that are known about, but not told:

The church’s story

When it comes to the story of your local church, similar things apply. It will be shaped by both listeners and tellers. There may be embarrassing stories about members, or stories we do not tell if one particular person is present. There will be a generally accepted larger story:

And associated typical stories:

And there will be unexpected aspects too. One village church has capital assets of almost a million pounds; at another there is an annual tradition of throwing buns from the church tower!

Just like individuals’ and families’ stories, the church’s larger story will express our values and priorities, the choices we make, the sort of things we do and the sort we are hardly likely to do, the kind of things that please us and the kind that upset us. It is an indicator of the church’s practical wisdom.

Rival versions of the same story

But one important difference between shared stories, such as those of the church, and most individuals’ stories, is the rival interpretation of events. Individuals telling their stories naturally present happenings with an interpretation they can accept. Happenings within a community or family, on the other hand, are often open to a number of different interpretations. For example, at one church the sale of the minister’s house twenty years ago is still recounted in quite contrasting ways. One version tells of how the denominational authorities, anxious to get their hands on some easy money, sold the house and moved the minister into a poky little place unable to contain the church office, the meetings of the church council and the Sunday School in the way the old one did. Another version tells of how much more comfortable the minister was living in a more modestly sized house where the children could feel at home without being constantly invaded by church members, a house which was also much more economic to run.

Rival stories like this also serve as rallying cries for different groups. Those who want to preserve as much of the old ways as possible – and who suspect the denominational authorities of ill will toward them – will retell the first version; those who feel that large prestigious houses are not at all what the modern church needs will prefer the second.

You may well find that there are alternative versions of important stories in your own church history.

Telling our own story

The time line

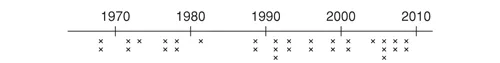

How can we begin to collect the stories which characterize our church life? A simple but very useful starting point is a time line. It’s best to start with the period of time that people can actually remember. Ideally, the way to do this is at a meeting arranged for the purpose, at which you ask people simply to mark on a line divided into years the date at which they joined the church. The result will look something like Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Time line showing when people joined your church

Some time lines are long, in the sense that memories go back for 60 or more years. Other churches have much shorter time lines; perhaps no one present has been a member for more than 20 years. The long time line probably indicates a settled community, while the short time line might simply belong to a new church, or it may be a sign of the transitory population in the area – for various reasons people generally move on from here.

There may also be gaps and clusters in the time line. Do they have a straightforward explanation? Perhaps a new housing estate was built nearby 20 years ago. Did the church undertake an evangelistic mission? Was a certain minister rather unpopular?

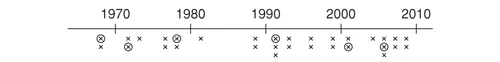

You can learn something more about yourselves by asking those who are members of the church council (or whatever the church decision-making body is called) to mark themselves again on the time line with a ring or in a different colour (see Figure 1.2). The resulting pattern may reveal that the majority of council members are drawn from those who have been with you the longest, or it may have a much more even spread. What, if anything, does this say about you and how you do things? You could expand the information on the time line by asking everyone who attends church over a sequence of Sundays to complete a card giving the date of their arrival and stating whether they are a member of the council, so that you get as full a picture as possible.

Figure 1.2 Distribution of church leaders along the time line

Collecting the memories

The next stage is to start collecting memories about the church. If you do this at a meeting, I suggest you divide into small groups of people who joined at approximately the same time. The members of each group are then invited to write down any events, incidents, and so on they especially remember. Encourage everyone to say how events or decisions were received (for example, was a particular event welcomed or resented?). Include a question about what they think the church is especially good at.

Alternatively, the information can be collected over a sequence of Sundays, inviting people to write down their memories. Or you could set up a small team of interviewers to collect the information, the stories and the opinions, and then write them up, at the very least, as a series of notes. If you have the time and energy, you could make a much more comprehensive time line, arranging some of the memories and stories by the appropriate year, either on a series of display boards or around the walls of the church...