eBook - ePub

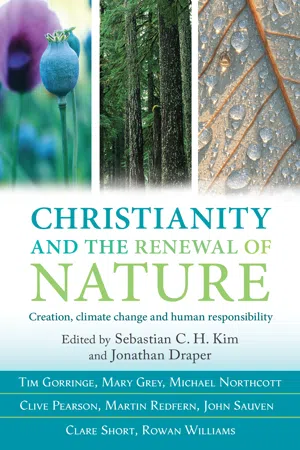

Christianity and the Renewal of Nature

Creation, climate change and sustainable living

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The reality of climate change, and the challenges it presents to sustainable living, is perhaps the key issue facing humanity at present. The developing ecological crisis raises profound questions for theology, religious traditions, politics and economics. This book examines the roots and causes of the global emergency from a variety of perspectives and look at the implications of the crisis for future sustainable living on the planet. The contributors include top theologians -- Rowan Williams, Tim Gorringe, Mary Grey, Michael Northcott and Clive Pearson -- as well as the environmental activist John Sauven, the BBC science producer Martin Redfern and the former Secretary of State for Environmental Development, Clare Short.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Christianity and the Renewal of Nature by Sebastian Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Renewing the face of the earth: Human responsibility and the environment

ROWAN WILLIAMS

Some modern philosophers have spoken about the human face as the most potent sign of what it is that we can’t master or exhaust in the life of a human other – a sign of the claim upon us of the other, of the depths we can’t sound but must respect. And while it is of course so ancient a metaphor to talk about the ‘face’ of the earth that we barely notice any longer that it is a metaphor, it does no harm to let some of these associations find their way into our thinking; because such associations resonate so strongly with a fundamental biblical insight into the nature of our relationship with the world we inhabit.

‘The earth is the LORD’s’, says the twenty-fourth psalm. In its context, this is primarily an assertion of God’s glory and overall sovereignty. And it affirms a relation between God and the world that is independent of what we as human beings think about the world or do to the world. The world is in the hands of another. The earth we inhabit is more than we can get hold of in any one moment or even in the sum total of all the moments we spend with it. Its destiny is not bound only to human destiny, its story is not exhausted by the history of our particular culture or technology, or even by the history of the entire human race. We can’t as humans oblige the environment to follow our agenda in all things, however much we can bend certain natural forces to our will; we can’t control the weather system or the succession of the seasons. The world turns, and the tides move at the drawing of the moon. Human force is incapable of changing any of this. What is before me is a network of relations and interconnections in which the relation to me, or even to us collectively as human beings, is very far from the whole story. I may ignore this, but only at the cost of disaster. And it would be dangerously illusory to imagine that this material environment will adjust itself at all costs so as to maintain our relationship to it. If it is more than us and our relation with it, it can survive us; we are dispensable. But the earth remains the Lord’s.

And this language is used still more pointedly in a passage like Leviticus 25.23: we are foreign and temporary tenants on a soil that belongs to the Lord. We can never possess the land in which we live, so as to do what we like with it. In a brilliant recent monograph, the American Old Testament scholar Ellen Davis points out that the twenty-fifth chapter of Leviticus is in fact a sustained argument about enslavement and alienation in a number of interconnected contexts. The people and the land alike belong to God – so that ‘ownership’ of a person within God’s chosen community is anomalous in a similar way to ownership of the land. When the Israelite loses family property, he must live alongside members of his family as if he were a resident alien (25.35); but the reader is reminded that in relation to God, the entire community, settled by God of his own gratuitous gift in the land of Canaan, has the same status of resident aliens. And when there is no alternative for the impoverished person but to be sold into slavery, an Israelite buying such a slave must treat him as a hired servant; if the purchaser is not an Israelite, there is an urgent obligation on the family to see that the person is redeemed. Davis points out that the obligation to redeem the enslaved Israelite is connected by way of several verbal echoes with the obligation defined earlier of redeeming, buying back, family land alienated as a result of poverty (vv. 24 –28). The language of redemption applies both to the land and to the people; both are in God’s hands, and thus the people called to imitate the holiness of God will be seeking to save both persons and property from being alienated for ever from their primary and defining relation to the God of the Exodus.1

A primary and defining relation: this is the core of a biblical ethic of responsibility for the environment. To understand that we and our environment are alike in the hands of God, so that neither can be possessed absolutely, is to see that the mysteriousness of the interior life of another person and the uncontrollable difference and resistance of the material world are connected. Both demand that we do not regard relationships centred upon us, upon our individual or group agendas, as the determining factor in how we approach persons or things. If, as this whole section of Leviticus assumes, God’s people are called to reflect what God is like, to make God’s holiness visible, then just or good action is action which reflects God’s purpose of liberating persons and environment from possession and the exploitation that comes from it – liberating them in order that their ‘primary and defining relation’ may be realized. Just action, towards people and environment, is letting created reality, both human and non-human, stand before God unhindered by attempts to control and dominate.

Responsibility for creation

It is a rather different reading of the biblical tradition from that often (lazily) assumed to be the orthodoxy of Judaeo-Christian belief. We hear regularly that this tradition authorizes the exploitation of the earth through the language in Genesis about ‘having dominion’ over the non-human creation. As has been argued elsewhere, this is a very clumsy reading of what Genesis actually says; but set alongside the Levitical code and (as Ellen Davis argues) many other aspects of the theology of Jewish Scripture, the malign interpretation that has latterly been taken for granted by critics of Judaism and Christianity appears profoundly mistaken. But what remains to be teased out is more about the nature of the human calling to further the ‘redemption’ of persons and world. If liberating action is allowing things and persons to stand before God free from claims to possession, is the responsibility of human agents only to stand back and let natural processes unfold?

In Genesis, humanity is given the task of ‘cultivating’ the garden of Eden: we are not left simply to observe or stand back, but are endowed with the responsibility to preserve and direct the powers of nature. In this process, we become more fully and joyfully who and what we are – as St Augustine memorably says, commenting on this passage: there is a joy, he says, in the ‘experiencing of the powers of nature’. Our own fulfilment is bound up with the work of conserving and focusing those powers, and the exercise of this work is meant to be one of the things that holds us in Paradise and makes it possible to resist temptation. The implication is that an attitude to work which regards the powers of nature as simply a threat to be overcome is best seen as an effect of the Fall, a sign of alienation. And, as the monastic scholar Aelred Squire points out, this insight of Augustine, quoted by Thomas Aquinas, is echoed by Aquinas himself in another passage where he describes humanity as having a share in the working of divine Providence because it has the task of using its reasoning powers to provide for self and others (aliis, which can mean both persons and things).2 In other words, the human task is to draw out potential treasures in the powers of nature and so to realize the convergent process of humanity and nature discovering in collaboration what they can become. The ‘redemption’ of people and material life in general is not a matter of resigning from the business of labour and of transformation – as if we could – but the search for a form of action that will preserve and nourish an interconnected development of humanity and its environment. In some contexts, this will be the deliberate protection of the environment from harm: in a world where exploitative and aggressive behaviour is commonplace, one of the ‘providential’ tasks of human beings must be to limit damage and to secure space for the natural order to exist unharmed. In others, the question is rather how to use the natural order for the sake of human nourishment and security without pillaging its resources and so damaging its inner mechanisms for self-healing or self-correction. In both, the fundamental requirement is to discern enough of what the processes of nature truly are to be able to engage intelligently with them.

All of this suggests some definitions of what unintelligent and ungodly relation with the environment looks like. It is partial: that is, it refuses to see or understand that what can be grasped about natural processes is likely to be only one dimension of interrelations far more complex than we can gauge. It focuses on aspects of the environment that can be comparatively easily manipulated for human advantage and ignores inconvenient questions about what less obvious connections are being violated. It is indifferent, for example, to the way in which biodiversity is part of the self-balancing system of the world we inhabit. It is impatient: it seeks returns on labour that are prompt and low cost, without consideration of long-term effects. It avoids or denies the basic truth that the environment as a material system is finite and cannot indefinitely regenerate itself in ways that will simply fulfil human needs or wants. And when such unintelligent and ungodly relation prevails, the risks should be obvious. We discover too late that we have turned a blind eye to the extinction of a species that is essential to the balance of life in a particular context. Or we discover too late that the importation of a foreign life-form, animal or vegetable, has upset local ecosystems, damaging soil or neighbouring life-forms. We discover that we have come near the end of supplies – of fossil fuels for example – on which we have built immense structures of routine expectation. Increasingly, we have to face the possibility not only of the now familiar problems of climate change, bad enough as these are, but of a whole range of ‘doomsday’ prospects. Martin Rees’s 2003 book Our Final Century outlined some of these, noting also that the technology which in the hands of benign agents is assumed to be working for the good of humanity is the same technology which, universally available on the internet, can enable ‘bio-terror’, the threat to release pathogens against a population.3 This feels like an ultimate reversal of the relation between humanity and environment envisaged in the religious vision – the material world’s processes deliberately harnessed to bring about domination by violence; though, when you think about it, it is only a projection of the existing history of military technology.

A. S. Byatt’s novel The Biographer’s Tale tells the story – or rather a set of interconnected stories – of a writer engaging with the literary remains of a diverse collection of people, including Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist.4 Late in the book (pp. 243 – 4), Fulla, a Swedish entomologist, holds forth to the narrator and his friends about the varieties of devastation the world faces because of our ignorance of insect life, specifically the life of bees:

She told fearful tales of possible lurches in the population of pollinators (including those of the crops we depend on for our own lives). Tales of the destruction of the habitats by humans, and of benign and necessary insects, birds, bats and other creatures, by crop-spraying and road-building … Of the need to find other (often better) pollinators, in a world where they are being extinguished swiftly and silently. Of the fact that there are only thirty-nine qualified bee taxonomists in the world, whose average age is sixty … Of population problems, and feeding the world, and sesbania, a leguminous crop which could both hold back desertification, because it binds soil, and feed the starving, but for the fact that no one has studied its pollinators or their abundance or deficiency, or their habits, in sufficient detail.

It is a potent catalogue of unintelligence.

Earlier in the book (p. 205), Fulla has said that ‘We are an animal that needs to use its intelligence to mitigate the effects of its intelligence on the other creatures’ – a notable definition in the contemporary context of what the Levitical call to redemption might mean. We cannot but use our intelligence in our world, and we are bound to use it, as Fulla’s examples suggest, to supply need, to avoid famine and suffering. If the Christian vision outlined by Aquinas is truthful, intelligence is an aspect of sharing in God’s Providence and so it is committed to providing for others. But God’s Providence does not promote the good only of one sector of creation; and so we have to use our intelligence to seek the good of the whole system of which we are a part. The limits of our creative manipulation of what is put before us in our environment are not instantly self-evident, of course; but what is coming into focus is the level of risk involved if we never ask such a question, if we collude with a social and economic order that apparently takes the possibility of unlimited advance in material prosperity for granted, and systematically ignores the big picture of global interconnectedness (in economics or in ecology).

Ecological questions are increasingly being defined as issues of justice; climate change has been characterized as a matter of justice both to those who now have no part in decision-making at the global level yet bear the heaviest burdens as a consequence of the irresponsibility of wealthier nations, and to those who will succeed us on this planet – justice to our children and grandchildren (this is spelled out clearly in Paula Clifford’s new book, Angels with Trumpets: The Church in a Time of Global Warming).5 So the major issue we need to keep in view is how much injustice is let loose by any given set of economic or manufacturing practices. We can’t easily set out a straightforward code that will tell us precisely when and where we step across the line into the unintelligence and ungodliness I have sketched. But we can at least see that the question is asked, and asked on the basis of a clear recognition that there is no way of manipulating our environment that is without cost or consequence – and thus also of a recognition that we are inextricably bound up with the destiny of our world. There is no guarantee that the world we live in will ‘tolerate’ us indefinitely if we prove ourselves unable to live within its constraints.

Is this – as some would claim – a failure to trust God, who has promised faithfulness to what he has made? I think that to suggest that God might intervene to protect us from the corporate folly of our practices is as unchristian and unbiblical as to suggest that he protects us from the results of our individual folly or sin. This is not a creation in which there are no real risks: our faith has always held that the inexhaustible love of God cannot compel justice or virtue; we are capable of doing immeasurable damage to ourselves as individuals, and it seems clear that we have the same terrible freedom as a human race. God’s faithfulness stands, assuring us that even in the most appalling disaster love will not let us go; but it will not be a safety net that guarantees a happy ending in this world. Any religious language that implies this is making a nonsense of the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament and the urgency of the preaching of Jesus.

But to say this is also to be reminded of the fact that intelligence is given to us; we are capable of changing our situation – and, as A. S. Byatt’s character puts it, using our intelligence to limit the ruinous effects of our intelligence. If we can change things so appallingly for the worse, it is possible to change them for the better also. But, in Christian terms, this needs a radical change of heart, a conversion; it needs another kind of ‘redemption’, which frees us from the trap of an egotism that obscures judgement. Intelligence in regard to the big picture of our world is no neutral thing, no simple natural capacity of reasoning; it needs grace to escape from the distortions of pride and acquisitiveness. One of the things we as Christians ought to be saying in the context of the ecological debate is that human reasoning in its proper and fullest sense requires an awareness of our participation in the material processes of the world and thus a sense of its own involvement in what it cannot finally master. Being rational is not a wholly detached capacity, examining the phenomena of the world from a distance, but a set of skills for finding our way around in the physical world.

An intelligent response to environmental crisis

The ecological crisis challenges us to be reasonable. Put like that, it sounds banal; but given the level of irrationality around the question, it is well worth saying, especially if we are clear about the roots of reasoning in these ‘skills’ of negotiating the world of material objects. I don’t intend to discuss in detail the rhetoric of those who deny the reality of climate change, except to say that rhetoric (as King Canute demonstrated) does not turn back rising waters. If you live in Bangladesh or Tuvalu, scepticism about global warming is precisely the opposite of reasonable: ‘negotiating’ this environment means recognizing the fact of rising sea levels; and understanding what is happening necessarily involves recognizing how rising temperatures affect sea levels. It is possible to argue about the exact degree to which human intervention is responsible for these phenomena (though it would be a quite remarkable coincidence if massively increased levels of carbon emissions merely happened to accompany a routine cyclical change in global temperatures, given the obvious explanatory force of the presence of these emissions), but it is not possible rationally to deny what the inhabitants of low-lying territories in the world routinely face as the most imminent threat to their lives and livelihoods.

And what the perspective of faith – in particular of Christian faith – brings to this discussion is the insight that we are not and don’t have to be God. For us to be reasonable and free and responsible is for us to live in awareness of our limits and dependence. It is no lessening of our dignity as humans, let alone our rationality and liberty as hum...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Renewing the face of the earth: Human responsibility

- 2 Visions of the end? Revelation and climate change

- 3 Consider the lilies of the field: Reading Luke’s Gospel and saving the planet

- 4 Hope, hype and honesty reporting global change: A still point on a turning planet

- 5 Disturbing the present

- 6 The concealments of carbon markets and the publicity of love in a time of climate change

- 7 Exploring a public theology for here on earth

- 8 Apocalypse now: Global equity and sustainable living – the preconditions for human survival

- Postscript: The climate change debate continues

- Notes

- Index