![]()

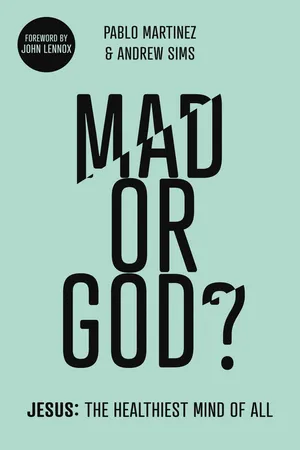

1. THE TEST OF PSYCHIATRY: WAS JESUS MENTALLY DISTURBED?

This man we are talking about either was (and is) just what he said, or else a lunatic, or something worse.

C. S. Lewis

Jesus has had a greater influence than any other person on individuals, and on history. Indeed, 2,000 years after his death the number of his followers continues to increase. During his lifetime he met with violent hatred and a shameful death. Now his followers are still persecuted and martyred in many parts of the world, and they encounter verbal attack and discrimination in many others. For those who know Jesus, he is everything; for those who do not, all possible means have been used to discredit him.

‘He’s raving mad. Why listen to him?’ his critics have been protesting for 2,000 years, and still insist today. Some say that Jesus is mad because they do not understand him, some because they reject him, and some have just never tried or bothered to listen.

What did he really say about himself? Could it be construed as the outpouring of a madman?

Why does it matter whether or not Jesus was mentally ill?

A powerful businessman became increasingly bombastic, noisy and rude to employees, clients and shareholders. He made decisions with long-lasting consequences arbritarily and without consulting his colleagues. Others in the firm realized that he was mentally ill and tried in all possible ways to keep him from public view. They realized that his authority and power would immediately be undermined if there was even a whiff of mental illness.

Why does it matter whether Jesus was mad or not? It matters because Jesus offers meaning, trust and credibility, authority, and a relationship built on love. If the view that Jesus is mad can be substantiated, then all of these disappear. To convince us that Jesus was psychiatrically deranged, there would have to be signs suggesting one or other of three groups of mental illnesses: psychosis (considered in chapter 2), other mental illness or personality disorder (considered in chapter 3).

When Jesus said of himself, ‘I am the good shepherd’ (John 10:11), that phrase, like so much else that he said, carried many associated meanings for his Jewish hearers because of their knowledge of the Old Testament: the coming king who will free us from Roman oppression, the promised Messiah, national and personal security, and self-respect. Some accepted him, but others said, ‘He is demon-possessed and raving mad. Why listen to him?’ (John 10:20). When Jesus spoke, this immediately attracted his critics, often with some religious authority, to launch into accusations of madness in order to undermine his credentials.

Really the Messiah?

The claim by his detractors that he was mad was inextricably linked to the realization that Jesus was the Messiah. The first hint was made by the Magi (wise men) at the time of his birth when they came to worship ‘the one who has been born king of the Jews’ (Matthew 2:2). This was an extraordinary endorsement from heathen scholars when greeting a baby!

The expression ‘Son of God’, which implies ‘Messiah’, is first used in Matthew’s Gospel by two demon-possessed men who shouted at Jesus (Matthew 8:29). They recognized that Jesus’ healing power came from God and that he was able to heal them from madness and violence.

When Jesus enabled Peter to walk on the water and calmed the storm on the lake, the disciples said to him, with grateful conviction, ‘Truly you are the Son of God’ (Matthew 14:33). Jesus put these questions to his disciples: ‘“Who do people say the Son of Man is? . . . But what about you? . . . Who do you say I am?” Simon Peter answered: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God”’ (Matthew 16:13–16).

At Jesus’ trial the high priest said to him, ‘I charge you under oath by the living God: Tell us if you are the Messiah, the Son of God’ (Matthew 26:63). In his reply Jesus accepted the claim. Finally, a centurion at the foot of the cross, in terror from the earthquake, said, ‘Surely he was the Son of God!’ (Matthew 27:54).

These witnesses came from different backgrounds and had differing opinions about Jesus, but all queried whether Jesus was indeed the Son of God, and therefore the Messiah. In Mark’s Gospel, hints that Jesus was the Messiah were linked with his imminent death.1 Jesus, and his disciples, claiming that he was the Messiah was not a boast, but proved to be a death warrant. For the Jewish leaders, declaring him mad was their only effective means to stop the spreading idea that he was the Messiah.

From early on in his ministry his disciples had come to realize that Jesus was ‘the Messiah’. Jesus himself believed this. He applied the Old Testament Scriptures about the ‘Suffering Servant’ and ‘God coming into his kingdom’ to himself, and, in so doing, he ‘was to court the charge of madness’.2 Jesus fulfilled the Old Testament prophecies about the Messiah: a descendant of Eve, from the seed of Abraham, a prophet like Moses, a king like David, a priest like Melchizedek, the servant of the Lord and the Son of man.3

‘Jesus is crazy’ is of course a cheap form of abuse, a deliberate put-down by those who want to dismiss him. Yet what he said and did was like no-one else throughout history. How do we explain his behaviour on earth, acting as a great leader, and his reputation since his death, the most venerated person of all time? Some of the statements that led to the accusation of madness were: ‘your sins are forgiven’, ‘the kingdom of God is coming’, ‘the King of the Jews’ and ‘today this Scripture is fulfilled in your hearing’. And he supported these colossal claims with the whole manner of his life.

C. S. Lewis’s ‘trilemma’ implies that either (1) what Jesus said is true, or (2) he is a liar, a fraud, or (3) a madman. As we said in the introduction, in this book we deal mainly with the claim that he was mad. Jesus shouted,

Whoever believes in me does not believe in me only, but in the one who sent me. The one who looks at me is seeing the one who sent me. I have come into the world as a light, so that no one who believes in me should stay in darkness . . . I did not speak on my own, but the Father who sent me commanded me to say all that I have spoken. I know that his command leads to eternal life. So whatever I say is just what the Father has told me to say.

(John 12:44–46, 49–50)

Jesus was not just a philosopher producing wise sayings for discussion among the intelligentsia. He claims to be speaking directly from God. As theologian and writer N. T. (Tom) Wright says, ‘The real reason for doubt is the shuddering fear that it is after all true. What if Jesus really were the mouthpiece of the living God? What if seeing him really did mean seeing the father?’4 What a terrifying idea! It is more comfortable to assume he is mad. In his lifetime some of his closest friends betrayed and denied him, and most people couldn’t really make him out. He was compelling but puzzling.5 But was he mad?

What is mental illness?

We now apply the principles of psychiatry to Jesus’ story. What is mental illness, mental disorder? For such questions to have any meaning, there has to be a clear threshold between normal experience and ‘caseness’ – mental disorder. Speech and behaviour that appears to be unintelligible does not necessarily indicate mental illness. If I cannot understand someone, that does not prove that person to be insane – it could even be something lacking in me!

Anna was a grandmother, with her stable and supportive family around her. She was active in her community and church. Her habits were regular, including completing the newspaper crossword every morning at breakfast. Inexplicably, she began to slow down and become very quiet. She became gloomy, grumpy, quite unlike her usual bright self, and gave up many of her activities. She had no appetite and had lost a lot of weight. She became apathetic and indecisive; she would sit still in her chair all day. Her family was very worried about her, and her doctor diagnosed depression and, because of her extreme weight loss, arranged for her to be admitted to hospital. There the diagnosis was confirmed, and appropriate treatment started. She began to improve and after a few months returned to her old self – picking up her previous activities and once more finishing the crossword every morning. She had suffered from a serious, potentially lethal, mental illness. Yet, following diagnosis and treatment, she made a full recovery.

June was the vicar of a small country parish. Towards the end of a long winter, she described everything as ‘going pear-shaped’. The churchwarden had a blazing row with another member of the congregation and promptly resigned. The treasurer had a serious illness and was absent from church for several months. The head teacher of the village school, of which June was a governor, had to take leave in the middle of the term. June’s husband had been working away from home for a few weeks, and her teenage son had given up on school work and was out most evenings. By April, June was completely exhausted, anxious and dejected; she felt that she could not take much more. After Easter she and her family had ten days’ holiday with her sister who lived in Spain, and away from home she felt much better. Despite her gloom and tension in March, June never suffered from a mental illness. Throughout, her body and mind were reacting appropriately to the almost intolerable demands being made upon her at that stressful time, and when the outside pressures were removed, there came a blessed relief from symptoms. If you had talked to June in late March, you would probably have thought that she was mentally ill, but this was not so.

We will focus strongly on diagnosis over the next few chapters. There is no single ‘mental illness’; there are many different psychiatric conditions, with varying features. How did the patient’s condition arise? What other states of mind are similar, and, most importantly of all, what is likely to happen in the future and, therefore, what should be done about it?

Diagnosis is a means of communication between doctors and others, and it is based on the ‘symptoms’ and ‘signs’ that the sufferer shows.6 The patient complains of symptoms, but physical signs are discovered on examination. In psychiatry, the complaints of the patient (feeling anxious) and observation by the clinician (agitation and tremor) are both described as symptoms, and added together to form signs of the diagnosis, anxiety disorder. The importance of diagnosis in psychiatry has increased as effective treatments have been developed.

Each mental illness shows a definite pattern, and illness is neither random nor arbitrary; what is said and done has meaning which may not be immediately apparent to the sufferer or the doctor. For example, depressive illness has a pattern, distinctive features, which are different from those of anorexia nervosa, because the symptoms that the sufferer describes, the onset of the condition, its course over time and its outcome, all differ. In the same way, the condition called schizophrenia differs radically from Alzheimer’s disease, the most frequent type of dementia. There are clear, established patterns for the different conditions, and a variation from these is exceptional rather than usual. To claim that someone is mentally ill, one must describe which symptoms and signs of which specific mental disorder a patient is demonstrating.

Features of mental illness

There are four features common to all mental illnesses:

- symptoms (what distresses the sufferer, as noted above)

- loss of function (inability to carry out normal activities)

- disturbance of relationships (family, friends, work)

- disturbance in self-image (how patients feel about themselves).

Symptoms include both the complaints that the sufferer makes, and signs – indicators of mental disorder apparent on examination but not complained of by the patient. For example, slowness of speech and limited gesture in severe depression are signs, often more noticeable to the doctor than the patient.

A psychiatrist seeks to under...