![]()

The Columbo moment (1:1–15)

Because we’re working quite closely with the Bible text, you’ll want to have a Bible open. Now is a good time to reread 1:1–15.

Jesus is God’s King

Remember the American television show, Columbo? It was daytime TV in the 1980s, and I (Andrew) always looked forward to it on sick days. Tim has never seen it because he’s too young, and wouldn’t have been allowed to anyway, because doctors’ kids can’t miss school for anything less than heart surgery.

Columbo was a classic detective show with a difference. Usually, the identity of the murderer is not revealed until the climax of the story, but in Columbo we find out ‘whodunit’ in the first five minutes. The enjoyment (or frustration) of the rest of the episode comes from watching our hero figure it out.

Similarly, in his Gospel, Mark tells us the punchline up front: ‘the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God’ (1:1). And then, in true Columbo style, we spend the rest of the Gospel waiting for Jesus’ followers to discover the truth.

But what exactly is Mark’s opening sentence telling us about Jesus? People might think of ‘Christ’ as Jesus’ surname, as if Mr and Mrs Christ had a son, but the Vocabulary tool tells us (e.g. by looking up ‘Christ’ in a dictionary) that Christ is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word Messiah, meaning God’s anointed King. Similarly, ‘Son of God’ is one of the ways that the Old Testament spoke of the King who was to come:

I will establish the throne of his kingdom for ever. I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son.

(2 Samuel 7:13–14)

I have set my King

on Zion, my holy hill...

‘You are my Son;

today I have begotten you.’

(Psalm 2:6–7)

So, by using both titles, ‘Christ’ and ‘Son of God’ together, Mark has really told us the same thing twice. We could paraphrase: ‘the beginning of the gospel of Jesus the King, the King’.

Lots of different things happen in the first few paragraphs following this introduction. We’re told about a man called John and his odd dietary habits; there’s a baptism; Jesus hangs out with a strange crowd in the wilderness; good news is preached in Galilee. But the Structure tool helps us to see that it all belongs together, and makes a single point. How? As we shall find him doing again and again, Mark encloses the mini-section in a pair of bookends that match each other. Verse 1 spoke of the gospel about a King. Verses 14–15 announce the gospel about a kingdom. Somehow the whole opening section is intended to convince us of the good news that the King(dom) has arrived.

To begin with, Mark takes us to the Old Testament to remind us that the King would not turn up unannounced: first there would come a ‘messenger’ or ‘voice’ to prepare the way. It’s a bit like when a celebrity comes to town. Before you see the limousine with blacked-out windows, you get (if the celebrity is important enough) a police outrider going on ahead, stopping the traffic. It would be strange for the front page of the tabloids to carry a photo of the outrider; he’s hardly the star of the show. But in this case, Mark spends five verses telling us about him. His logic seems to be this: ‘If I can convince them that John the Baptist is the outrider mentioned by Isaiah, then I’ll get their hearts beating faster as they realize who is expected next on the scene.’

If we read Mark’s description of John in isolation, we are at a loss to make sense of the details. But when we use the Context tool, we find that almost every feature of vv. 4–8 corresponds to something in the prophecy of vv. 2–3:

| Prophecy (vv. 2–3) | How Mark convinces us that John is the perfect fit (vv. 4–8) |

| The forerunner is described as a ‘messenger’ or ‘voice’ – his role is to speak. | Mark goes out of his way to describe John’s ministry not simply as ‘baptizing’, but also ‘proclaiming a baptism’. |

| The forerunner can be found ‘in the wilderness’. | John’s ministry took place ‘in the wilderness’. |

| The forerunner is there to ‘[p]repare the way’ for someone. | John is pointing to the one who comes ‘after me’. |

| ? | ‘John was clothed with camel’s hair and wore a leather belt around his waist.’ |

The bottom row of the table is the trickiest, but that’s just because we know the Bible less well than Superman films. Let us explain ... if you saw someone with underpants on the outside of his trousers and a big red-and-yellow ‘S’ on his front, you’d have no difficulty figuring out who he was dressed as. Similarly, the camel’s-hair tunic and leather belt ensemble would have been instantly recognizable by a first-century Jew who knew their Old Testament. Time for you to do some work for yourself, with the help of the Quotation/Allusion tool.

DIG DEEPER: Quotation/Allusion tool

The first half of Mark’s quote comes from Malachi 3:1, which is part of a longer prophecy about the coming of the Lord and the messenger who precedes him. Look up Malachi 4:5 to find out the name of this messenger.

Look up 2 Kings 1:7–8 to find out what the guy with this name was famous for wearing. Bingo!

In all of these different ways, then, Mark is showing us that John the Baptist fits the profile of Malachi’s ‘messenger’ or Isaiah’s ‘voice’. According to v. 5, ‘all the country of Judea and all Jerusalem were going out to him’, and the popularity of his ministry is noted by the first-century Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities 18.5.2). But John the Baptist doesn’t want the limelight for himself. He is only the outrider. In starkly self-effacing terms, he insists that he is not worthy to untie Jesus’ shoelaces (v. 7). He protests that his ministry is, in comparison with the powerful reality of Jesus’ Holy Spirit baptism, nothing more than making people wet (v. 8). In every way he points away from himself to the one who is to come after him.

Jesus is God’s King. The voice in the wilderness proclaims it.

Next, Mark takes us to the baptism of Jesus. Two details of the account underline Jesus’ identity. The first is the ‘Spirit descending on him like a dove’ (v. 10). Two verses earlier (Context tool), John had told us that the coming one would baptize with the Holy Spirit, and the visible descent of the Spirit on Jesus unmistakably identifies him: he receives the Spirit that he might baptize others in the Spirit.

The second detail is the message that God the Father shouts from heaven: ‘You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased’ (v. 11). We’ve already mentioned that ‘Son of God’ is a kingly title, but here we have it from the lips of the Creator himself. It’s not often that God makes an announcement over the heavenly tannoy. This is another way of telling us that the arrival of Jesus is a really, really big deal.

Jesus is God’s King. The voice from heaven shouts it.

Next, the Spirit thrusts Jesus into the wilderness where he is with the wild animals (vv. 12–13). But it’s not a typical David Attenborough BBC wildlife scene, because alongside the lions and rock badgers, we find Satan tempting Jesus, and angels serving him. Jesus’ arrival is accompanied by spiritual activity of most unusual intensity.

Jesus is God’s King. The spiritual powers recognize it.

Finally, Jesus arrives in Galilee to begin his public ministry. It would be rather arrogant to turn up at a social gathering and announce, as you walk through the door, ‘The party can get started now!’ But that is exactly what Jesus does. ‘The kingdom of God is at hand,’ he says (v. 15). ‘I’m here.’

Jesus is God’s King. His own preaching emphasizes it.

Jesus has come to save

If we were digging deep enough for, say, a one-storey extension, we would stop there. But let’s keep on and see if we can go further with v. 13. In our reading of what other people have said about Mark’s Gospel, we came across a number of interpretations of the phrase: ‘he was with the wild animals’:

- The ‘Jesus-knows-what-you’re-going-through’ theory. The Roman historian, Tacitus, records that Christians persecuted by Nero in the 60s AD were ‘covered with the hides of wild beasts and torn to pieces by dogs’ (Annals 15.44). By mentioning that Jesus also faced the threat of wild animals, Mark is telling his early readers that Jesus can identify with them in their suffering.

- The ‘Jesus-is-greater-than-Nebuchadnezzar’ theory. The suggestion is that Jesus’ experience parallels the fate of the Babylonian king described in Daniel 4:28–37, who spends time in the wilderness with wild animals, wet with dew (just as Jesus would have been wet following his baptism).

The fatal flaw in these interpretations is that Mark himself suggests neither of them. In other words, they fall foul of the Author’s Purpose tool, the most important tool of them all.

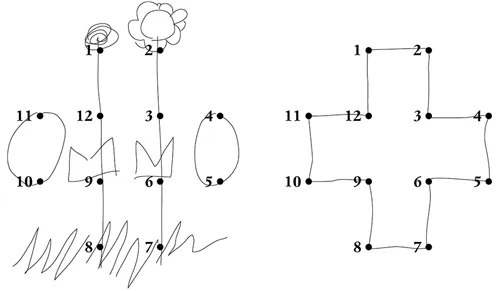

If we are using the Author’s Purpose tool correctly, we are not at liberty to draw our own biblical or theological connections from ideas that Mark mentions: ‘Here is a mention of wild animals, and so that could mean...’, and off we go into Daniel or Tacitus or wherever. Instead, we should look for the connections that Mark explicitly draws. One of our friends explains this using the analogy of a game of dot-to-dot. See below two attempts by kids at our church. The child on the left makes use of some of the dots, but connects them in her own delightfully imaginative way. The child on the right, by following the numbers, gets the author’s intended connection between the dots. The pictures that emerge are quite different.

What then, if any, are Mark’s own clues about how to interpret Jesus’ forty-day safari in the wilderness? We’ve noticed already that the angels in attendance point to his kingly majesty. But is there more that can be said?

As always, we need to look closely at the text, and when we do so, we find that it reads rather strangely: ‘The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. And he was in the wilderness...’ (vv. 12–13). Why say it twice? You would never say, ‘I went to Bristol. And I was in Bristol.’ It seems that the location is especially important to Mark, and the Context tool shows us why. For it was ‘in the wilderness’ that Isaiah had said a voice would cry out (v. 3), and ‘in the wilderness’ that John appeared baptizing (v. 4). By reusing that phrase, Mark is showing us that it is Isaiah and John (not Nero or Nebuchadnezzar) who will help us join the dots correctly.

Isaiah was writing just before the Israelites went into exile in Babylon because of their sin. Against a backdrop of doom and judgment, his ‘voice crying in the wilderness’ announces rescue and forgiveness.

John’s ministry in the wilderness was all about forgiveness too. He preached ‘a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins’ (v. 4), and as people were baptized, they were ‘confessing their sins’ (v. 5). But washing with water couldn’t wash the heart; only the baptism of the Holy Spirit could achieve that.

And so Jesus is driven into the wilderness. Having done the work using the Context tool, the significance of this desert location is abundantly clear: Jesus has come to do the thing that Isaiah prophesied and John’s baptism symbolized. He has come to bring forgiveness.

It’s nice that once you lock on to the author’s purpose, even the little details start to slot into place. As we were reading through the ‘salvation in the wilderness’ section of Isaiah, we found that it centres on a servant whom God delights in and puts his Spirit upon (42:1) – we couldn’t help thinking of the dove and the heavenly commendation at Jesus’ baptism. Then we found that God promised to pour out his Spirit on his people – we couldn’t help thinking of John’s promise that Jesus would baptize with the Spirit. We even found wild animals honouring God (43:20)! As for the forty days, if the wilderness in Isaiah was symbolically the place that sin takes you to, and from which you need deliverance, then the most obvious parallel is the forty years of wandering in the desert earlier in Israel’s history (see Numbers 14:34).

Jesus has come to save.

The Columbo experience

We’ve come a long way in our understanding of Mark 1:1–15. But how should it affect us today? How ought we to respond? In one sense, we have not understood any part of the Bible until we can answer that question.

Fortunately, Jesus tells us exactly what response is required (v. 15). Direct imperatives can be a real help when we’re using the ‘So What?’ tool. If you’re not a grammar boffin, and you don’t know an imperative from an indicative, think back to your driving theory test. You’ll remember that in the Highway Code, information signs are often rectangular: ‘The next Motorway Services has a KFC’, while warning signs come in red triangles: ‘Road narrows on both sides’, and signs giving orders come in a blue or red circle: ‘Keep left’ or ‘No entry’. The imperatives are the circle ones. They are the places where we are told exactly what to do and not do. And here is one such case: ‘...