- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Burning pyres, nuns on the run, stirring courage, comic relief.The story of the Protestant Reformation is a gripping tale, packed with drama. It was set in motion on 31 October 1517 when Martin Luther posted his ninety-five theses on the castle church door in Wittenberg. What motivated the Reformers? And what were they really like?In this lively, accessible and informative introduction, Michael Reeves brings to life the colourful characters of the Reformation, unpacks their ideas, and shows the profound and personal relevance of Reformation thinking for today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Unquenchable Flame by Michael Reeves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Going medieval on religion:

the background to the Reformation

As the fifteenth century died and the sixteenth was born, the old world seemed to die at the hands of a new one: the mighty Byzantine Empire, last remnant of Imperial Rome, had collapsed; then Columbus discovered a new world in the Americas, Copernicus turned the universe on its head with his heliocentrism, and Luther literally re-formed Christianity. All the old foundations that once had seemed so solid and certain now crumbled in this storm of change, making way for a new era in which things would be very different.

Looking back today, it feels nigh on impossible even to get a sense of what it must have been like in that era. ‘Medieval’ – the very word conjures up dark, gothic images of chanting cloister-crazed monks and superstitious, revolting peasants. All very strange. Especially to modern eyes: where we are out-and-out democratic egalitarians, they saw everything hierarchically; where our lives revolve around nurturing, nourishing and pampering the self, they sought in everything to abolish and abase the self (or, at least, they admired those who did). The list of differences could go on. Yet this was the setting for the Reformation, the context for why people got so passionate about theology. The Reformation was a revolution, and revolutions not only fight for something, they also fight against something, in this case, the old world of medieval Roman Catholicism. What, then, was it like to be a Christian in the couple of centuries before the Reformation?

Popes, priests and purgatory

Unsurprisingly, all the roads of medieval Roman Catholicism led to Rome. The apostle Peter, to whom Jesus had said ‘You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church’, was thought to have been martyred and buried there, allowing the church to be built, quite literally, upon him. And so, as once the Roman Empire had looked to Rome as its mother and Caesar as its father, now the Christian empire of the Church looked still to Rome as its mother, and to Peter’s successor as father, ‘papa’ or ‘pope’. There was a slightly awkward exception to this: the Eastern Orthodox Church, severed from the Church of Rome since the eleventh century. But every family has a black sheep. Other than that, all Christians recognized Rome and the pope as their irreplaceable parents. Without Father Pope there could be no Church; without Mother Church there could be no salvation.

A papal procession

The pope was held to be Christ’s ‘vicar’ (representative) on earth, and as such, he was the channel through whom all of God’s grace flowed. He had the power to ordain bishops, who in turn could ordain priests; and together, they, the clergy, were the ones with the authority to turn on the taps of grace. Those taps were the seven sacraments: baptism, confirmation, the Mass, penance, marriage, ordination and last rites. Sometimes they were spoken of as the seven arteries of the Body of Christ, through which the lifeblood of God’s grace was pumped. That this all looks rather mechanistic was precisely the point, for the unwashed masses, being uneducated and illiterate, were considered incapable of having an explicit faith. So, while an ‘explicit faith’ was considered desirable, an ‘implicit faith’, in which a person came along to church and received the sacraments, was considered perfectly acceptable. If they stood under the taps they received the grace.

It was through baptism that people (generally as infants) were first admitted to the Church to taste God’s grace. Yet it was the Mass that was really central to the whole system. That would be made obvious the moment you walked into your local church: all the architecture led towards the altar, on which the Mass would be celebrated. And it was called an altar with good reason, for in the Mass Christ’s body would be sacrificed afresh to God. It was through this ‘unbloody’ sacrifice offered day after day, repeating Christ’s ‘bloody’ sacrifice on the cross, that God’s anger at sin would be appeased. Each day Christ would be re-offered to God as an atoning sacrifice. Thus the sins of each day were dealt with.

Yet wasn’t it obvious that something was missing from this sacrifice, that Christ’s body wasn’t actually on the altar, that the priest was only handling mere bread and wine? This was the genius of the doctrine of transubstantiation. According to Aristotle, each thing has its own ‘substance’ (inner reality) as well as ‘accidents’ (appearance). The ‘substance’ of a chair, for instance, could be wood, while its ‘accidents’ are brownness and dirtiness. Paint the chair and its ‘accidents’ would change. Transubstantiation imagined the opposite: the ‘substance’ of the bread and wine would, in the Mass, be transformed into the literal body and blood of Christ, whilst the original ‘accidents’ of bread and wine remained. It may all have seemed a bit far-fetched, but there were enough stories doing the rounds to persuade doubters, stories of people having visions of real blood in the chalice, real flesh on the plate and so on.

The moment of transformation came when the priest spoke Christ’s words in Latin Hoc est corpus meum (‘this is my body’). Then the church bells would peal and the priest would raise the bread. The people would normally only get to eat the bread once a year (and they never got to drink from the cup – after all, what if some ham-fisted peasant spilt the blood of Christ on the floor?), but grace came with just a look at the raised bread. It was understandable that the more devoted should run feverishly from church to church to see more masses and thus receive more grace.

The service of the Mass was said in Latin. The people, of course, understood not a word. The trouble was, neither did many of the clergy, who found learning the service by rote quicker than learning a whole new language. Thus when parishioners heard ‘Hocus pocus’ instead of Hoc est corpus meum, who knows whose mistake it was? Even priests were known to fluff their lines. And with little understanding of what was being said, it was hard for the average parishioner to distinguish Roman Catholic orthodoxy from magic and superstition. For them the consecrated bread became a talisman of divine power that could be carried around to avert accidents, given to sick animals as a medicine or planted to encourage a good harvest. Much of the time the Church was lenient towards semi-pagan folk Christianity, but it is a testimony to how highly the Mass was revered that it decided to act against such abuses: in 1215, the fourth Lateran Council ordered that the transformed bread and wine ‘are to be kept locked away in a safe place in all churches, so that no audacious hand can reach them to do anything horrible or impious’.

Underpinning the whole system and mentality of medieval Roman Catholicism was an understanding of salvation that went back to Augustine (AD 354–430); Augustine’s theology of love, to be precise (how ironic that this theology of love would come to inspire great fear). Augustine taught that we exist in order to love God. However, we cannot naturally do so, but must pray for God to help us. This he does by ‘justifying’ us, which, Augustine said, is the act in which God pours his love into our hearts (Romans 5:5). This is the effect of the grace that God was said to channel through the sacraments: by making us more and more loving, more and more just, God ‘justifies’ us. God’s grace, on this model, was the fuel needed to become a better, more just, righteous and loving person. And this was the sort of person who finally merited salvation, according to Augustine. This was what Augustine had meant when he spoke of salvation by grace.

Talk of God pouring out his grace so that we become loving and so merit salvation might have sounded lovely on Augustine’s lips; over the centuries, however, such thoughts took on a darker hue. Nobody intended it. Quite the opposite: how God’s grace worked was still spoken of in attractive, optimistic ways. ‘God will not deny grace to those who do their best’ was the cheery slogan on the lips of medieval theologians. But then, how could you be sure you really had done your best? How could you tell if you had become the sort of just person who merited salvation?

In 1215, the fourth Lateran Council came up with what it hoped would be a useful aid for all those seeking to be ‘justified’: it required all Christians (on pain of eternal damnation) to confess their sins regularly to a priest. There the conscience could be probed for sins and evil thoughts so that wickedness could be rooted out and the Christian become more just. The effect of the exercise, however, was far from reassuring to those who took it seriously. Using a long official list, the priest would ask questions such as: ‘Are your prayers, alms and religious activities done more to hide your sins and impress others than to please God?’ ‘Have you loved relatives, friends or other creatures more than God?’ ‘Have you muttered against God because of bad weather, illness, poverty, the death of a child or a friend?’ By the end it had been made very clear that one was not righteous and loving at all, but a mass of dark desires.

The effect was profoundly disturbing, as we can see in the fifteenth-century autobiography of Margery Kempe, a woman of Norfolk. She describes how she left one confession so terrified of the damnation that such a sinner as she surely deserved that she began to see devils surrounding her, pawing at her, making her bite and scratch herself. It is tempting for the modern mind quickly to ascribe this to some form of mental instability. Margery herself, however, is quite clear that her emotional meltdown was due simply to taking the theology of the day seriously. She knew from the confession that she was not righteous enough to have merited salvation.

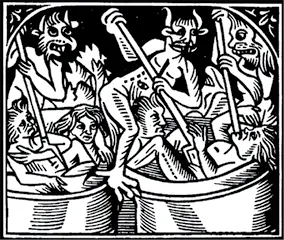

One of the torments of purgatory

Of course, the Church’s official teaching was quite clear that nobody would die righteous enough to have merited salvation fully. But that was no cause for great alarm, for there was always purgatory. Unless Christians died unrepentant of a mortal sin such as murder (in which case they would go to hell), they would have the chance after death to have all their sins slowly purged from them in purgatory before entering heaven, fully cleansed. Around the end of the fifteenth century, Catherine of Genoa wrote a Treatise on Purgatory in which she described it in glowing terms. There, she explained, the souls relish and embrace their chastisements because of their desire to be purged and purified for God. More worldly souls than Catherine’s, however, tended to be less upbeat about the prospect of thousands or millions of years of punishment. Instead of enjoying the prospect, most people sought to fast-track the route through purgatory, both for themselves, and for those they loved. As well as prayers, masses could be said for souls in purgatory, in which the grace of that Mass could be applied directly to the departed and tormented soul. An entire purgatory industry evolved for exactly this reason: the wealthy founded chantries (chapels with priests dedicated to saying prayers and masses for the soul of their sponsor or his fortunate beneficiaries); the less wealthy clubbed together in fraternities to pay for the same.

Robert Grosseteste (1168–1253)

Not everyone was prepared to toe the official line unquestioningly, of course. To take just one example, Robert Grosseteste, who became bishop of Lincoln in 1235, believed that the clergy should first and foremost be about preaching the Bible, not giving Mass. He himself rather unusually preached in English, rather than Latin, so that he might be understood by the people. He clashed a number of times with the pope (when, for example, a non-English-speaking priest was appointed to his diocese), going so far as to call the pope an antichrist who would be damned for his sin. Few could get away with such language, but Grosseteste was so famous, not only for his personal holiness, but as a scholar, scientist and linguist, that the pope felt unable to silence him.

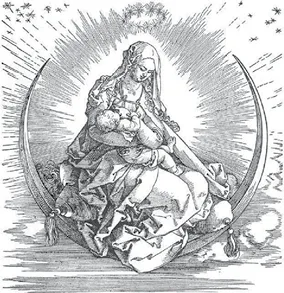

Another aspect of medieval Roman Catholicism that was impossible to ignore was the cult of the saints. Europe was filled with shrines to various saints, and they were important, not just spiritually, but economically. With enough decent relics of its patron saint, a shrine could ensure a steady stream of pilgrims, making everyone a winner, from the pilgrims to the publicans. As much as anything, what seemed to fuel the cult was the way in which Christ became an increasingly daunting figure in the public mind through the Middle Ages. More and more, the risen and ascended Christ was seen as the Doomsday Judge, all-terrible in his holiness. Who could approach him? Surely he’d listen to his mother. And so, as Christ receded into heaven, Mary became the mediator through whom people could approach him. Yet, having been accorded such glory, Mary in turn became the inapproachable star-flaming Queen of Heaven. Using the same logic, people began to appeal to her mother, Anne, to intercede with her. And so the cult of St Anne grew, attracting the fervent devotion of many, including an obscure German family called the Luthers. It wasn’t just St Anne; heaven was crammed with saints, all very suitable mediators between the sinful and the Judge. And the earth seemed full of their relics, objects that could bestow some of their grace and merit. Of course, the authenticity of some of these relics was questionable: it was a standing joke that there were so many ‘pieces of the true cross’ spread across Christendom that the original cross itself must have been far too huge for a man to lift. But then, Christ was omnipotent.

Mary as Queen of Heaven, woodcut by Albrecht Dürer, 1511

The official line was that Mary and the saints were to be venerated, not worshipped; but on the ground that was much too subtle a distinction for people who were not being taught. All too often the army of saints was treated as a pantheon of gods, and their relics treated as magical talismans of power. Yet how could the illiterate be taught the complexities of this system of theology, and so avoid the sin of idolatry? The stock answer was that, even in the poorest churches, they were surrounded by pictures and images of saints and the Virgin Mary, in stained glass, in statues, in frescoes: these were ‘the Bible of the poor’, the ‘books of the illiterate’. Lacking words, the people learnt from pictures. It has to be said, however, that the argument is a bit hollow: a statue of the Virgin Mary was hardly capable of teaching the distinction between veneration and worship. The very fact that services were in Latin, a language the people did not know, betrays the reality that teaching was not really a priority. Some theologians tried to get around this by arguing that Latin, as a holy language, was so powerful it could even affect those who did not understand it. It sounds rather unlikely. Rather, the fact was that people did not need to understand in order to receive God’s grace. An unformed ‘implicit faith’ would do. Indeed, given the absence of teaching, it would have to.

Dynamic or diseased?

If ever you should be so unfortunate as to find yourself in a roomful of Reformation historians, the thing to do to generate some excitement is to ask loudly: ‘Was Christianity on the eve of the Reformation vigorous or corrupt?’ It is the question guaranteed to start a bun-fight. A few years ago it would hardly have caused a murmur; everyone then seemed happily agreed that before the Reformation the people of Europe were groaning for change, hating the oppressive yoke of the corrupt Roman Church. Now that view will not wash.

Historical research, especially from the 1980s and on, has shown beyond any doubt that in the generation before the Reformation, religion became more popular than ever. Certainly people had their grumbles, but the vast majority clearly threw themselves into it with gusto. More masses for the dead were paid for, more churches were built, more statues of saints were erected and more pilgrimages were made than ever before. Books of devotion and spirituality – as mixed in content as they are today – were extraordinarily popular among those who could read.

And, the religious zeal of the people meant that they were eager for reform. Throughout the fourteenth century, monastic orders were reforming themselves, and even the papacy underwent some piecemeal attempts at reform. Everyone agreed that there were a few dead branches and a few rotten apples on the tree of the Church. Everyone could laugh when the poet Dante placed Popes Nicholas III and Boniface VIII in the eighth circle of hell in his Divine Comedy. Of course there were corrupt old popes and priests who drank too much before Mass. But the very fact that people could laugh shows how solid and secure the Church appeared. It looked like it could take it. And the fact that they wanted to prune the dead wood only shows how they loved the tree. Such desires for reform never came close to imagining that there might be fatal rot in the trunk of the tree. After all, wanting better popes is something very different from wanting no popes; wanting better priests and masses very different to wanting no separate priesthood and no masses. And this Dante also showed: not only did he punish bad popes in his Inferno, he also meted out divine vengeance on those who opposed popes, for popes, good or bad, were, after all, the vicars of Christ. Such were most Christians on the eve of the Reformation: devoted, and devoted to the improvement, but not the overthrow, of their religion. This was not a society looking for radical change, only a clearing-up of acknowledged abuses.

So, vigorous or corrupt? It is a false antithesis. Christianity on the eve of the Reformation was undoubtedly popular and lively, but that ...

Table of contents

- The Unquenchable Flame

- Contents

- Prologue: Here I stand

- 1 Going medieval on religion: the background to the Reformation

- 2 God’s volcano: Luther

- 3 Soldiers, sausages and revolution: Ulrich Zwingli and the Radical Reformers

- 4 After darkness, light: John Calvin

- 5 Burning passion: the Reformation in Britain

- 6 Reforming the Reformation: the Puritans

- 7 Is the Reformation over?

- Reformation timeline

- Further reading