- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1951 this book is a study of village system in southern Tanzania, which at the time of publication was thought to be unique. Each village consisted not of a group of kinsmen but an age-set: a group of male contemporaries, together with their wives and young children. The book is concerned with the structure of these villages and the values expressed in them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Good Company by Monica Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Antropología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SELECT DOCUMENTS RELATING TO NYAKYUSA AGE-VILLAGES

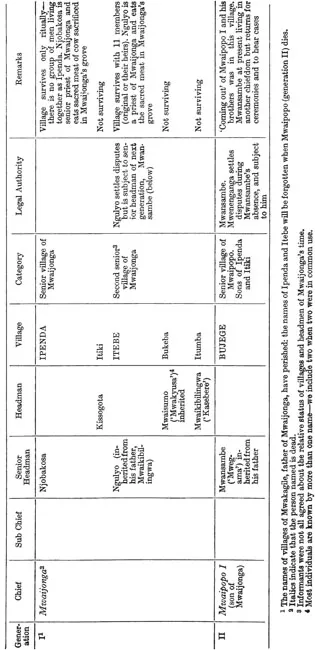

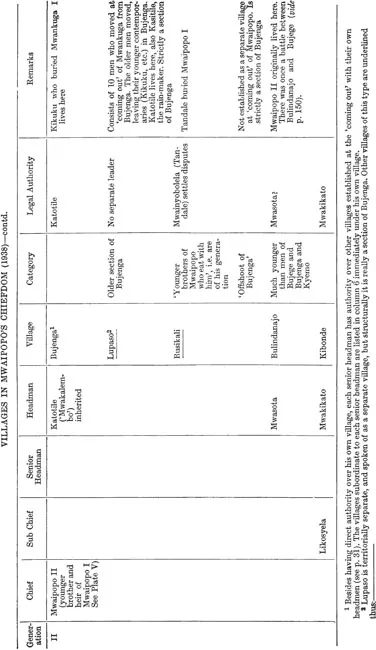

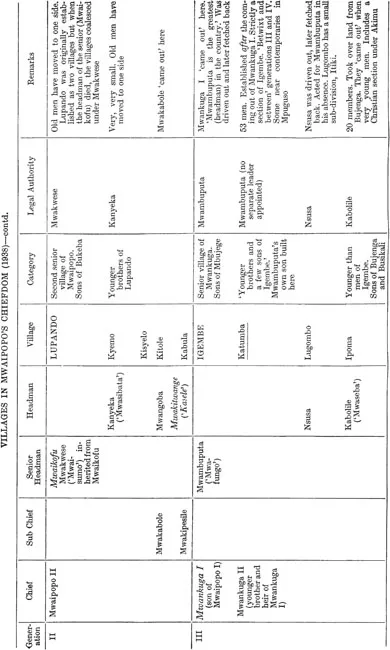

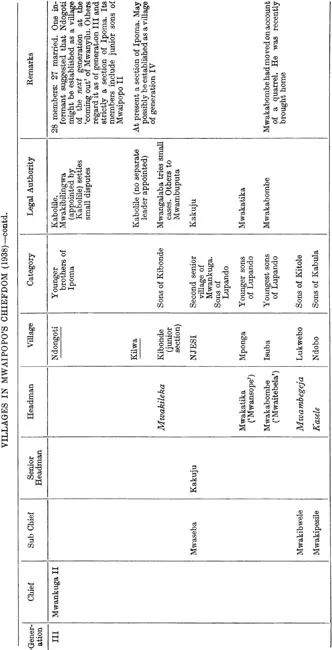

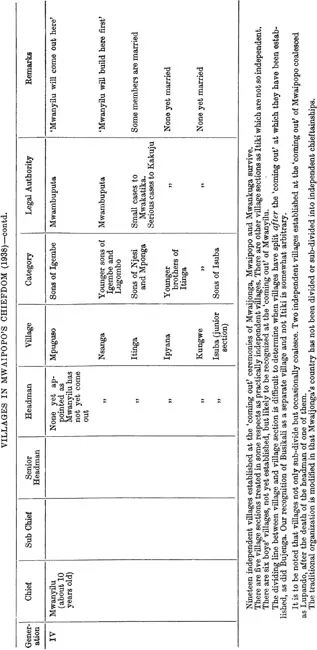

1. VILLAGES IN MWAIPOPO’S CHIEFDOM (1938) Information from numerous informants

2. THE ‘COMING OUT’ (UBUSOKA)

Mwaikambo (clerk and son of a chief).1

‘The village headmen begin to talk among themselves, saying: “Our sons have grown up, should we not establish them?” So they go to tell the chief, saying: “Our sons have grown up, let us show them to the country.” Two chiefs always “come out”. We call them the senior and the junior. It is an old custom which is still followed that two chiefs should “come out”.

‘So the village headmen seek a doctor to make them a medicine horn and treat the tails of chieftainship with medicine. The village headmen take council together and choose two senior headmen to “come out” with the chiefs. These senior headmen drink medicine (embondanya) with the chiefs.

‘When many people, together with the two young chiefs, have come together the doctor gives powdered medicine (embondanya) to the chiefs and the senior headman chosen for each chief. They give a spear of chieftainship, and a horn, and tail to each of the men chosen as senior headmen—one for each chief. Each senior headman then binds the horn to the blade of the spear, and standing with his own chief and many men and women, raises the spear to the sky. The women trill and each party goes to its place of “coming out” on the pasturage. Each chief, with his followers, goes to his own place. The men dance; sometimes they have drums, sometimes not.

‘Then when each party has reached it own place they make fire with fire sticks. The chief just simulates the action of fire-making then his senior headman takes the sticks and makes fire by friction. When they have built the shelters for sleeping in they warm themselves at the fire they have made; they do not take fire from the houses of men. If there are many of them then there will be three or four shelters, if few, then only one shelter. The men and their chief who has “come out” sleep in these shelters and enjoy themselves together (nukwangala). The first day they kill two head of cattle. Also they plant “the tree of coming out” (umpiki gwa busoka) which is called ulupando. They plant it with a man who has come out previously, a man of their fathers’ generation, he begins to plant, then he explains to them what to do, saying “plant”, then the new senior headman plants it.

‘While they sleep in these shelters with their cattle, they eat food which they take from their fathers, bananas, and milk, and other food. From time to time their father, the chief, gives them a bull to kill. During the “coming out” food is very plentiful. If people pass on the road they honour them and give them food, and make love to them that they may build there. They remain in their shelters, they do not go about much. If the chief is stingy they teach him a lesson by taking bananas; they say: “Know that we are important people, we are those who have ‘come out’ and we are your parents.” Later on they play drums—I think only in recent years. And the village headmen seize a woman, the daughter of a commoner, as a wife for the chief.

‘The horn is the luck of the chiefs, that many people may come to build. Binding the horn to the blade of the spear is to show that the chief is one who has “come out” (unsoka); it is as if he were carried aloft (i.e. “chaired”)1. We show his greatness (“seniority”) to people, then we trill.

‘The fire made with fire sticks is to symbolize the new chieftainship. We do not take the old fire of the old men.

‘The medicine is to make the chief heavy (nsito), that it may be apparent that he is a chief.

‘The ulupando tree is a memorial of the “coming out”, that men may come and say: “So and so planted this tree when he came out.” Some say it is to show the power (amaka) of the chief, because if it does not grow it is said that his chieftainship will perhaps not flourish; then they will say: “Let us move and plant elsewhere.” It is said that the spear of chieftainship is to fight battles; it is strength, manhood; it is treated with medicines.

‘The tails are those with which battles are fought. When men go to war the senior headman grasps the tail. If the tail does not lead them well they return from the fight. It, also, they treat with medicines.’

3. A LAND DISPUTE BETWEEN VILLAGES OF THE SAME CHIEFDOM

This case was discussed with a great number of informants. We first quote the account written by Mwaisumo (our clerk) which sums up the earlier discussions. ‘Mwansambe and Mwakalembo are quarrelling over the land of Ipoma. Both are village headmen of the older generation of Mwaipopo (the chief). Mwansambe is the senior, Mwakalembo the junior. Mwansambe is senior village headman of Mwaipopo. Mwakalembo is the next on his side (see table, pp. 181—2).

‘At the “coming out” of Mwaipopo the old men gave Mwansambe the land of Bujege, and said that his junior Mwakalembo should build on the land of Busikali. He (Mwakalembo) built with Mwakwese, the man of Seba.

‘When the “coming out” of Mwankuga, Mwaipopo’s son, was held, Mwansambe sent to his junior Mwakalembo, saying: “At your place here we are going to build the house of our wife Kalinga, that is to say we are going to plant the ulupando tree of our child Mwankuga here.” Mwakalembo agreed, but in secret he thought to himself: “My senior wants to seize my village! See he is building the great house at my place, and I am a junior!” So they brought out Mwankuga with Mwafungo as his senior headman, and Mwaseba Kabolile as a junior, and they planted the ulupando tree. Mwafungo built with his people and Mwaseba Kabolile with his. Later on Mwansambe arranged for his “sons”, i.e. Mwafungo and his fellows, to go to his side, and Mwakalembo thought that his land was saved. He had thought that his senior was taking his country, but lo, the latter had moved!

‘At that time Mwafungo went to enter into an inheritance1 in MuNgonde (i.e. on the Lake-shore plain). On his return he went to the side from which he had come. He sought a bull with which to say: “Fathers, I have arrived.” Mwansambe called his junior Mwakalembo saying: “Our son has arrived, they are eating the meat there without our having discussed together where we should kill, or where we should eat the meat.” (cf. pp. 271—4.)

‘So now Mwansambe wants to give his child Mwafungo a homestead site in which to build, he wishes to give him one at the ulupando tree where he first established him, and he has told his junior Mwakalembo so. Mwakalembo objected, saying: “How can you give him my homestead? Where shall I go?”

‘Mwansambe said they could both build there together.

‘Mwakalembo said “No.”

‘Mwansambe said: “How can you refuse? The site is mine, and I am your senior. Do you not see the ulupando tree which I planted for my child Mwafungo?”

‘Mwakalembo replied: “Yes, I see it, but you went away and left it, you and your children. I gave thanks thinking my land had escaped capture.”

‘Mwansambe said: “And the ulupando tree, do you tell us that it was seized also?”

‘Mwakalembo replied: “No, I don’t deny the ulupando tree, but when you pray you pray in your homestead, in the house of your wife. If you wish you can plant again at your place.”

‘Mwansambe said: “Why do you quarrel with me, Mwakalembo, I, your father, your senior, I who gave you land on which I said your fellow, Mwafungo should also build, since you are both my children?”

‘Mwakalembo replied: “The land about which we are quarrelling is mine, it is the place of my blood. I spilt blood, I seized it from Mwaipaja when I fought with him.”

(For originally this land about which they are quarrelling was Mwakwese’s, it was where Seba’s house was built. Then that Mwaipaja of whom they speak was the assistant village headman—a senior man. The followers of Mwakalembo made love to the wives, they approached them when they (the women) went to draw water. Mwaipaja was angry and called out his men to fight with the followers of Mwakalembo. Mwaipaja was defeated, and fled. The followers of Mwakalembo took his homestead. Mwaipaja was driven out: he built at Lupata where Kalunda and his men are now.)

‘It is here that Mwansambe planted the ulupando tree. It is this land that Mwakalembo means when he says that his land escaped seizure by his senior when he went away again with his followers! Mwansambe says: “See, it is mine also, my father moved Mwaipaja aside, that my junior should build here.”

‘Mwakalembo says: “I got it by conquest, I spilt my blood.”

‘People commenting on the case in private say that Mwansambe is wrong, the country is really Mwakalembo’s. Many say that although the case is put off it is not finished, Mwansambe will be overcome, and so Mwaipopo himself thinks.

‘Mwaseba Kabolile and Mwafungo Mwambuputa are those who hold the country now, they are the children of Mwansambe and Mwakalembo. Mwenenganga, who began speaking (at the trial in court), is the junior (‘brother’) of Mwansambe but he holds all the seniority of Mwansambe because Mwansambe himself is not in the country, he has moved. The Mwakalembo who is standing there is not Mwakalembo himself, but his son. And the Mweneganga Mwakoloma who is speaking is a junior, but he speaks because he knows how to speak—he has a “good tongue” (i.e. is an orator). And Ngulyo also is a junior—he is speaking because he knows how to speak. All of these are village headmen, senior men, fathers of Mwafungo and Mwaseba Kabolile.’

The case was twice discussed at greath length in Lupata Court but no judgement was given. Some maintained that were a judgement given war would result, because the losers would attack. Mwaipopo himself, as president of the court, was said to be afraid to give judgement lest he suffer from ‘the breath’ or witchcraft of the offended parties. He refused to hear the case a third time and, as Kasitile pointed out, sixteen months after the second hearing Mwaipopo was sleeping in the village of Bujenga (Mwakalembo’s village), and it was Mwakalembo and his men who w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Illustrations

- Maps

- I. Introductory

- II. Village Organization

- III. Economic Co-Operation

- IV. Values

- V. Mystical Interdependence

- VI. The Maintenance of Order

- VII. Characteristics of an Age-Village Organization

- Select Documents Relating to Nyakyusa Age-Villages

- Bibliography

- Index