- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Impact of Multiple Childhood Trauma on Homeless Runaway Adolescents

About this book

Originally published in 1999, the author addresses the American tragedy of some two million youth running away from home each year. This title proposes a model for examining the relationship between multiple types of childhood trauma – physical, sexual and psychological abuse, exposure to domestic violence – and psychological functioning in a sample of 140 homeless adolescents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Impact of Multiple Childhood Trauma on Homeless Runaway Adolescents by Michael DiPaolo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

Introduction

A thing which has not been understood inevitably reappears; like an unlaid ghost it cannot rest until the mystery has been solved and the spell broken (Freud, 1909).

Statement of the Problem

Before finishing this paragraph, another youth will have run away from home. While estimates of the homeless and runaway youth population vary in the 1.5–2 million range, no one really knows the extent of this national epidemic (Stefanidis, 1988). To adequately address this issue, one must first understand who these youth are.

Historically, the notion of “runaway” has many different connotations. Early theories viewed the runaway as an “adventurer,” akin to Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn (Janus, McCormack, Burgess, & Hartman, 1987) or “psychoneurotic” (Aichorn, 1932; Armstrong, 1935; cited in Stefanidis, 1988). Consistent across these views is that the act of running away is interpreted as deviant. This even led to the inclusion of the diagnosis of “Runaway Reaction” in the DSM-II.

In the late 1960’s and 70’s, another viewpoint was considered. While we have come to use the term “runaway,” the more apt term may be “throwaway.” For these are youth “who are left stranded, high and diy, on the concrete reefs of the city when their shipwrecked families founder and go under” (Ritter, 1987, p. 26). They leave home, whether by force or reluctant choice, because of the disturbing conditions within their families. In distinct contrast to the earlier notions, increasingly more systemic factors are viewed as the precursors to running away.

Physical, sexual or psychological abuse almost always plays a contributing factor in this scenario. Viewed in this light, the flight from home can be seen as the only alternative for the youth in order to survive. In a nationwide survey in 1991, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) reported that 60% of the youths in shelter or transitional living programs were physically or sexually abused by their parents. Stefanidis, Pennbridge, MacKenzie, and Pottharst (1992) report that 78% of their Hollywood sample of youth staying in shelters disclosed physical and/or sexual abuse at home.

Not coincidentally, the national figures for child abuse are even more staggering. In 1991, 2.7 million children were reported abused, and nearly 1,400 died from child abuse (National Committee for Prevention of Child Abuse, cited in Chandler, 1992). Consider that countless acts of abuse go unreported and the prevalence of this problem cannot be denied.

Child abuse, however, is not the only trauma that affects the lives of these youth. Exposure to domestic violence and community violence must also be examined to fully understand the magnitude of victimization. Every fifteen seconds, an incident of spousal abuse occurs in the United States (Browne, 1993). Tremendous increases in community violence occurred throughout the 1980’s, and continue into the 1990’s. For example, one out of five teenage and young adult deaths was gun related in 1988—the first year which firearm death for both Black and White teens exceeded the number of all natural causes of death combined (Richters & Martinez, 1993).

Once out of the home, the battle has only just begun. If the runaway youth lands in the “system” of children’s protective services, the outlook may not be too bright due to the overcrowding of this system. Eventually, many of the runaways will land on the street. In the NASW survey, 38% of youth seeking shelter in runaway programs had been in foster care within the previous year. Consider that the federal government allocated $66.6 million for services to runaways in its fiscal year 1997 budget (National Network for Youth, 1996), less than the $73.2 million spent by one private agency, Covenant House, in fiscal year 1996 (Covenant House report, 1996), and it becomes clear why the problem is only getting worse.

Due to many of these factors, the runaway adolescent often reaches the age of eighteen with few, if any, skills. Legally defined as an adult, the developmental needs more closely resemble early adolescence. What awaits in the future for this individual is one of four possibilities: chronic homelessness, prison, early death, or turning one’s life around. Unfortunately, only a small minority achieves this last and only positive outcome.

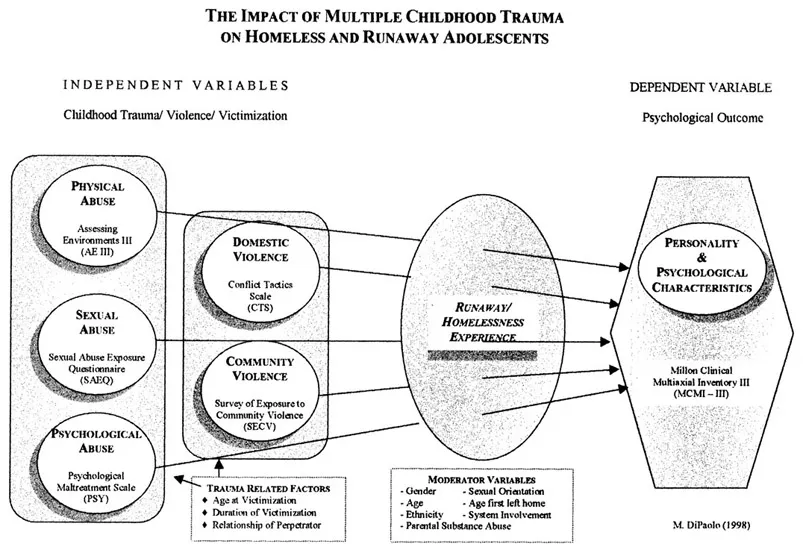

Something can be done, however, to improve the plight of the adolescent runaway. To address this issue, one must examine the devastating psychological impact of childhood trauma and violence on this individual. This book proposes a model of understanding current psychological functioning based upon the effects of multiple trauma—physical, sexual, and psychological child abuse, and exposure to domestic and community violence (see Figure 1).

Major impetus in developing this model comes out of the study of multiple trauma. Finkelhor and Dziuba-Leatherman (1994) coined the term “developmental victimology” to provide a framework for understanding its effects. Dutton (1995) has suggested a model in which “harsh parenting” and other experiences of violence “develop chronic traumatic stress symptoms which exist as long term sequels of the early abuse victimization” (p. 301). Rowan and Foy (1993) suggested that the perspective of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder may best fit the syndrome seen in survivors of abuse, and it is hypothesized that this may also be the case for homeless and runaway youth.

In expanding on the growing body of research on this population, this study explored the relationship between multiple childhood trauma and psychological functioning, as measured by the MCMI-III, presented by 18–21 year old homeless and runaway adolescents. In testing the proposed model, the purpose of the project was to establish correlational relationships and develop causal paths predictive of outcome. Such a model could then provide professionals other avenues of working with this population whose needs are multidimensional.

Definition of Terms

Sexual Abuse: Any sexual contact, coerced or otherwise, between an adult and a child less than 18 years of age. This may include intercourse, oral contact, fondling, and exhibitionism (Green, 1993). For this study, it is measured by self-report on a modified form of the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire (SAEQ) (Rowan, Foy, Rodriguez, & Ryan, 1993). See Appendix E.

Figure 1

Proposed Model

Physical Abuse: An act of commission by a child caretaker that involves either demonstrable harm or endangerment to a child less than 18 years of age (NCCAN, 1988), often characterized by overt physical violence or excessive punishment (Malinosky-Rummell & Hansen, 1993). In this study, it is measured by self-report on the Physical Punishment Scale of the Assessing Environments III (AEIII) (Berger, Knutson, Mehm, & Perkins, 1988). See Appendix F.

Psychological Abuse: Acts of omission and commission by a child caretaker which are judged by community standards and professional expertise to be psychologically damaging to the behavioral, cognitive, affective, or physical functioning of a child less than 18 years. In this study, it is measured by self-report on the psychological maltreatment scale (PSY) (Briere & Runtz, 1988). See Appendix G.

Exposure to Domestic Violence: The witnessing by a child less than 18 years of age of physical and/or verbal abuse, violence, or battering of one’s caretaker committed by another of one’s caretakers. In this study, it is measured by self-report on the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) (Straus, 1979). See Appendix H.

Exposure to Community Violence: The direct experience or witnessing of acts of violence by an individual. Examples of such acts include assault, use or possession of a weapon, drug trafficking, being chased, murder, and suicide. In this study, it is measured by self-report on a screening version of the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence (SECV) (Richters & Saltzman, 1990). See Appendix I.

Homeless and Runaway Adolescent: Youth away from home at least overnight without parental or caretaker permission, or those with no parental, foster, or institutional home, such as pushouts (urged to leave) and throwaways (left home with parental knowledge or approval without an alternative place to stay) (Department of Health and Human Services, 1988, cited in Robertson, 1992). In this study, this status is given by virtue of living in a crisis shelter for homeless and runaway adolescents and applies to adolescents between 18–21 years of age.

Overview of the Book

This book will first provide a review of the literature pertinent to the study. This includes an historical overview of the problem, a review of the homeless and runaway youth population, and an examination of the multiple independent variables of childhood trauma. The review concludes with a synthesis of findings, highlighting the differences and developments proposed by the current study. Finally, the hypotheses of the study are offered.

Following the review of the literature is the presentation of the methodology. This includes information about the host agency, subjects, design, instrumentation, procedures, and data analysis for the study. Copies of the instruments can be found in the appendices.

The results section then details the findings and data analyses which tested the study’s hypotheses, focusing on the development of the causal paths predictive of outcome on the MCMI-III.

The discussion section summarizes these findings and discusses their significance, again focusing on the paths predictive of outcome. The book’s proposed model is evaluated. Treatment implications and considerations for future research are offered.

Chapter II

Review of the Literature

The Review of the Literature is organized in the following manner:

- A historical overview of our understanding of victimized youth.

- An examination of the independent variables divided in two sections: child abuse (sexual, physical, and psychological) and exposure to other violence (domestic violence and community violence).

- An overview of the effects of multiple trauma and the development of PTSD.

- A review of the specific population under study, homeless and runaway youth.

- A synthesis of the review, highlighting the manner in which the proposed study extends our understanding of the issue.

- Hypotheses.

Historical Overview

In light of the topic of this project, a unique perspective of victimized youth will be offered. The issues of runaway youth, child abuse, and childhood trauma will be integrated into one historical presentation. This history will focus primarily from 1870 to the present and can be divided into roughly four periods.

Despite the more recent uproar over its incidence, child abuse has existed since the beginning of civilization, taking on such forms as infanticide, killing of the first bom, abandonment, and child slavery (Kalmer, 1977). Stemming back to the ancient Roman law and further elaborated under English Common Law (which is the basis for American law), children were considered the property of their father. Although English Common Law also stated that parents were responsible to provide their children with adequate nurturing and support, parental power was absolute and discipline extremely severe. American parenting styles evolved partly from this history, with physical discipline as a primary child rearing technique. In effect, Kalmer (1977) claims that “custom and tradition have designated children to be objects of persecution” (p. 1).

Pre-1870 History

Prior to this century, little advancement in our treatment of children occurred. In the 1820’s, the first “houses of refuge” were established for ungovernable or vagrant children in New York (1826) and Philadelphia (1829). These placements were designed to give children the necessary discipline in order for them to behave properly.

Early public response to the runaway was actually quite sympathetic. The runaway was viewed as an “adventurer,” a perception communicated through perhaps the most famous runaway in American lore, Huck Finn. This view considers the runaway healthy and independent, dissatisfied with the confines of home life and wanting to explore the world. As will be discussed later, this perception would change as these youth began to be seen as social problems.

Period 1 (1870–1930): The Awareness Period

In 1874, the first challenge to the absolute power of parents came in the case of Mary Ellen Wilson, an eight year old girl who was routinely starved and physically beaten by her parents. It was the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals that intervened to provide her legal protection, citing animal rights laws in her defense. As this case began to receive widespread support, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was established as the nation’s first organization concerned with children’s rights.

Subsequently, the first child labor laws were passed before the turn of the century. The first children’s court was also established in 1899. The issue of child maltreatment would now begin to be studied. However, as noted by Langmeier and Matejcek (1973, as cited in Benedek, 1985), this period between the latter half of the nineteenth century and the early 1930’s could be entitled the “empirical” period. It was marked by unsystematic observations of children living in institutions, such as orphanages and hospitals. High incidence of early death in children separated from their parents sparked scientific curiosity.

Sigmund Freud provides the groundwork for our understanding of trauma in some of the earliest psychological literature. In 1896, Freud reported 18 cases of hysteria in all of which he uncovered a history of sexual abuse in the patient’s childhood. Although he later recanted on these findings, attributing them to Oedipal fantasies, it is noted that he never published a case (e.g., “Dora”) in which sexual allegations could be translated entirely as remembered fantasies (Goodwin, 1985).

Freud (1926) defined a traumatic situation as an experience of “helplessness on the part of the ego” when faced with an event in which “external and internal, real and instinctual dangers converge.” Dynamically, a traumatic experience “presents the mind with an increase of stimulus too powerful to be dealt with or worked off in the normal way, and this must result in permanent disturbances of the manner in which the energy operates” (Freud, 1917).

Being a one-person theory, psychodynamic theory would offer understandings of the runaway which focused on individual pathology. The act of running away was seen as a response to the unresolved parental, primarily Oedipal, conflicts of childhood (Rosenheim and Robey, as cited in Stefanidis, 1988). Specifically, when triggered by an overwhelming stimulus, the child would flee. Thus, running was seen as a behavioral manifestation of psychopathology. Subsequently, the runaway was tabbed with a deviant label, such as “ps...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- TABLES

- FIGURES

- APPENDICES

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER II: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

- CHAPTER III: METHODS

- CHAPTER IV: RESULTS

- CHAPTER V: DISCUSSION

- REFERENCES

- INDEX