![]()

PART I

STATE SHINTŌ

![]()

CHAPTER I

SOME PRIMARY ASPECTS

The study of the sources from which a great people derive the inspiration of their major ideals and loyalties must ever be of importance to the rest of the world. The appropriateness and even the necessity of such study become especially clear in the case of the relationship of Shintō to the Japanese national life. For, whether or not we regard Shintō as a religion, the fact remains that no other great nation of the present shows a more vital dependence on priestly rituals and their concomitant beliefs than does modern Japan. To find really pertinent parallels in the historical stream that has fed directly the culture of the West one must go back beyond the church-state liaison of the middle ages of Christendom to the hierarchies of classical Rome and Greece, or even farther back into the past to the sacerdotal communities of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

It is an extraordinary fact of contemporary civilization that among the great powers of the world one can find a nation which is attempting to secure social and political cohesion through the strength of a ceremonial nexus that was normal in occidental culture between two and four thousand years ago. If, as has been said recently, scientific study, by using its own methods and speaking in its own terms, has discovered that the reality of religion lies in “the celebration, dramatization, and artistic representation of the felt values of any society”,1 then it is to Japan that the world must turn for the most comprehensive of all modern efforts to utilize such ritualistic agencies for vivifying and achieving the chief ends of the national life. It is this situation that lends particular fascination to the study of Shintō.

To understand Japan and the inner forces that shape her and the problems with which she wrestles within her own borders it is essential to know something of the ramifications of Shintō in the thought and practice of the people. Support for such a statement can be found in the fact that from childhood the Japanese are taught that attitudes and usages connected with the shrines of Shintō are vitally related to good citizenship. To be a worthy subject of the realm requires loyalty to certain great interests for which the shrines are made to stand. These attitudes are deliberately fostered on a large scale by the government. The shrines and their ceremonies are magnified in the state educational system as foremost among recognized agencies for the promotion of what is commonly designated kokumin dōtoku, or national morality. They are thus accorded a place of chief distinction among the approved means for representing to the people the values of good citizenship and for firmly uniting the nation about the Imperial Throne.

The following citation of a typical modern Japanese interpretation of the significance of Shintō may perhaps suffice to give cogency to the assertions just made.

“Students of this religion have been struck with the simplicity of its doctrine. It enforces no especial moral code, embraces no philosophical ideas, and, moreover, it has no authoritative books to guide believers. Its one peculiar feature is the relation it holds towards the Imperial Family of Japan, whose ancestors are made the chief object of worship. This religion, if indeed it can rightly be called a religion at all, amounts to ancestor-worship—the apotheosis of the Japanese Imperial Family. This fact naturally brings about two results: one is that Shintō can never be propagated beyond the realms of the Japanese Emperor; the other, that it has helped to a very great extent the growth of the spirit of loyalty of Japanese subjects toward their head, and has enshrined the Imperial Family with such a degree of sacredness and reverence that it would be difficult to name another ruling family which is looked up to by its subjects with the same amount of loyal homage and submissive veneration. It is, indeed, a unique circumstance in the history of the nations that, during the two thousand five hundred years of its sway, the position of the Japanese Imperial Family as head of the whole nation has never once been disputed, nor even questioned, by the people. Of course, it is true that the dynasty has experienced many vicissitudes, but, although the actual government has at times been in the hands of powerful nobles and Shōguns, the throne has, nevertheless, been always kept sacred for the descendants of Jimmu, the first Emperor.”2

All of the statements in the above quotation require careful examination and it is to such a study that the following pages are dedicated.

Buddhism has been called the creed of half Japan. There is a very real sense in which Shintō may be called the creed of all Japan, coloring deeply, as it does, the mind of her sixtynine million people and affecting profoundly the primary aspects of the national life. The history of Shintō is an important part of the history of Japan as a whole and a knowledge thereof is necessary to the attainment of an adequate appreciation of the genesis of Japanese thought, institutions, manners and customs, and religion.

We turn to a preliminary study of the nature of Shintō as revealed in its history. It is possible to make an introductory delimination of the subject by means of a definition. In so doing it is recognized that a definition is hardly more than an epitomized description in terms of significant features and that the sense of what is significant varies with the investigator. In explaining the manifold sociological and psychological data which we find in Shintō it is very difficult to avoid the introduction of a personal equation. There are ten or a dozen good definitions of Shintō in existence, all varying more or less according to the individual viewpoints of those attempting the elucidation. For example: Shintō is the indigenous religion of the Japanese people; it is the Way of the Gods; it is “kami-cult,” a form of definition in which kami signifies the deities of Japan as distinct from those brought into the country through foreign contacts; it is pan-psychism or hylozoism; it is the racial spirit of the Japanese people (Yamato Damashii); it is the sacred ceremonies conducted before the kami; it is the essence of the principles of imperial rule; it is a system of correct social and political etiquette; it is the ideal national morality; it is a system of patriotism and loyalty centering in emperor worship (“Mikadoism”); it is, in its pure and original form, a nature worship; or, over against chis, Shintō, correctly understood, is ancestor worship; or, again, it is an intermixture of the worship of nature and of ancestors; and, lastly, it is, in its earliest stages, a lower nature religion in which are merged elements of animism, naturism, and anthropolatry, evolving later into an advanced form of nature religion, and, finally, under the influence of Buddhism and Confucianism, achieving speculative and ethical components of a high order.

We have noted a number of definitions that have been advanced by different Japanese scholars. Manifestly, they are not all reconcilable one with another, although they can be harmonized to a large extent. Perhaps the chief value of such brief descriptions lies in the fact that they state fields of interest and indicate points of view from which data may be collected and lines of a study developed. If we go back to the statement of the nature of religion noted at the opening of our discussion, we may find a unifying point of view in a definition of Shintō as the characteristic ritualistic arrangements and their underlying beliefs by which the Japanese people have celebrated, dramatized, interpreted, and supported the chief values of their national life.

In dealing, with material that has been submitted to the many different interpretations that have been noted above it is necessary to predetermine in some way the limits of the field of investigation. For purposes of critical study it is best to take the data which the national government itself has included in the so-called Shintō classification. When we approach the matter from this direction we find four main fields of activity in Shintō: first. the ceremonies of the Imperial Household; second, Domestic Shintō, centering in the kami-dana, or god-shelves of the private homes; third, Shrine Shintō, also called State Shintō, embodied in the ceremonies of the public shrines; and, fourth, Sect Shintō, also called Religious Shintō, expressed in the activities of the many churches of the various Shintō denominations.

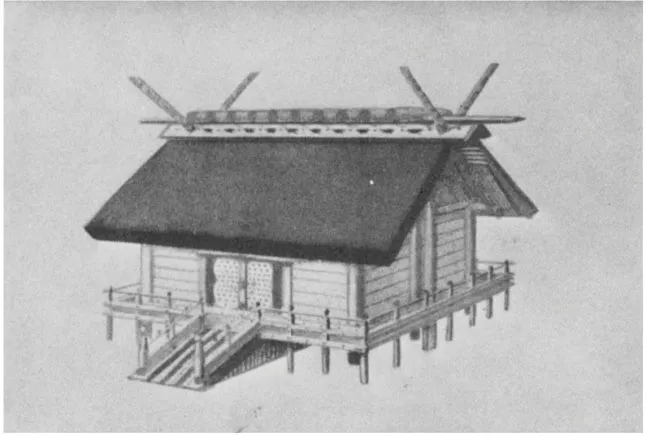

A Sketch of the Inner Shrine of Ise

Dedicated to the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu-Ōmikami.

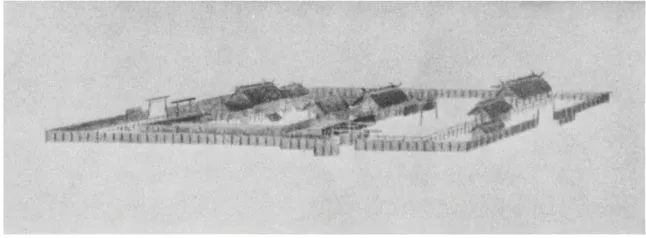

A Birďs-Eye View of the Sacred Precincts of the Inner Shrine of Ise

By courtesy of the Meiji-Japan Society of Tōkyō.

As a matter of fact, it affords a more rigorous classification if we distinguish only three kinds, namely, Domestic Shintō, Shrine or State Shintō, and Sect Shintō, since the ceremonies of the Imperial Household may be classified under either the first or the second of the forms just enumerated. As far as public aspects are concerned, then, we have only two types, namely, Shrine Shintō (Jinja Shintō) and Sect Shintō (Shūha Shintō). The elucidation of the characteristics of these two great branches of Shintō and the distinctions to be made between them constitute the subject matter of the ensuing discussion.

We turn first to the consideration of the nature of the Shintō places of worship. In contemporary Japanese law the institutions which are called “shrines” are generally designated jinja, from shin or jin, meaning “deity”(kami in pure Japanese) and sha, or ja, which in this connection is best rendered “house” or “dwelling place.” The shrine, or jinja, then, is a house or dwelling place in which the deity or deities, worshipped in the local rites, are supposed to live, or where they are believed to take up residence when summoned by appropriate ceremonies. They are the holy places where the kami may be found and communicated with. Japanese law permits the use of the term jinja only in connection with the traditional institutions of original Shintō wherein the kami are enshrined. The institutions of Buddhism and of the existing Shintō sects are denied the right to use the designation. We can preserve the distinction if we speak of the local foundations of State Shintō as shrines, of those of Buddhism as temples (tera) and of those of the Shintō sects as churches or chapels (kyōkai).

Jinja is thus a modern Sino-Japanese legal designation and does not represent the earliest known usage. Older and more widely used terms employed in the literature to indicate the abodes of Shintō deities are miya or omiya, yashiro or miyashiro, hokora, hokura, and mimuro. Miya (mi, honorific prefix, ya, “house”) and omiya (o-mi, double honorific) are the designations most commonly met with. It is not necessary to venture on an extended explanation of this varied terminology here. Suffice it to say that all the terms just listed may properly be taken to mean dwelling place or superior dwelling place in one form or another.3

The Shintō shrine may be a small god-house of wood or stone casually met with by the wayside. It may be a Grand Imperial Shrine of Ise or a Great Meiji Shrine of Tōkyō, including in its appointments extensive landed holdings and numerous costly buildings along with various objects of ceremony and art, with a total valuation of millions of yen.

The ordinary shrine includes a definite enclosure of land, usually rectangular in shape, surrounded by a sacred fence or wall, one or more buildings where the deities are enshrined and, generally, certain auxiliary structures where special ceremonies are conducted, business transacted, or properties stored. The immediate entrance to the shrine is generally guarded by two stone lions arranged one on either side of the approach. In the case of shrines to the grain-goddess, Inari, the lions give place to the images of foxes, animals to which popular belief attributes the functions of messengers to this deity. Encompassing the shrine proper or adjacent thereto may lie more or less extended areas devoted to landscape gardening and parkland or utilized as a source of revenue. Associated with the great Meiji Shrine of Tōkyō is a magnificent equipment providing for all sorts of athletic sports. The shrines, in their diversity of history, of ceremony and of architectual style, present a complicated and almost endless field of study. The most archaic type of shrine is simply a replica of the primitive house of ancient times, consisting of a small structure of natural wood, thatched with reeds or straw, the principal rafters in front and rear projecting through the roof, the total building elevated on piles in a manner that suggests the Swiss lake-dwellings or some of the Indonesian types of house architecture built above water.

Access to the shrine is gained through an opening in the fence or wall at the front, placed ex...