![]()

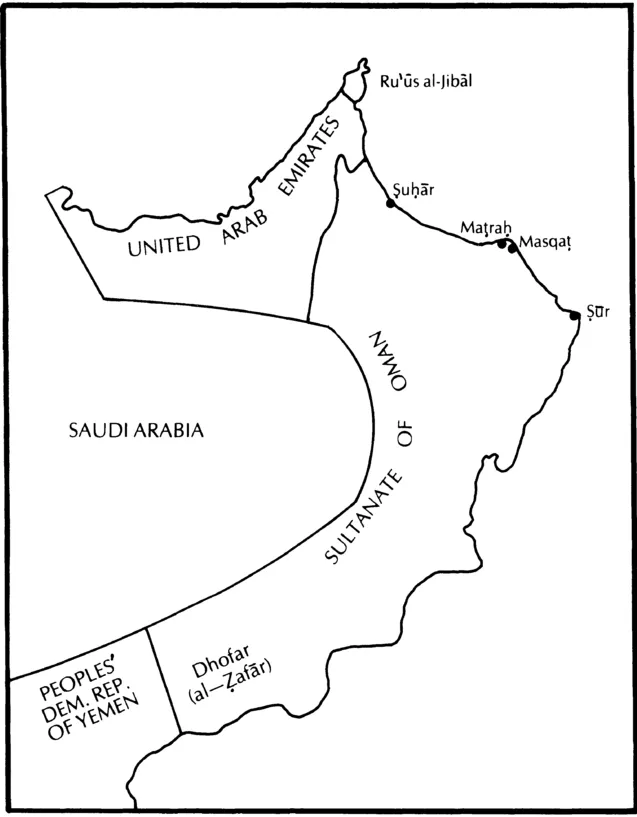

Map 1: boundaries of the modern Sultanate of Oman

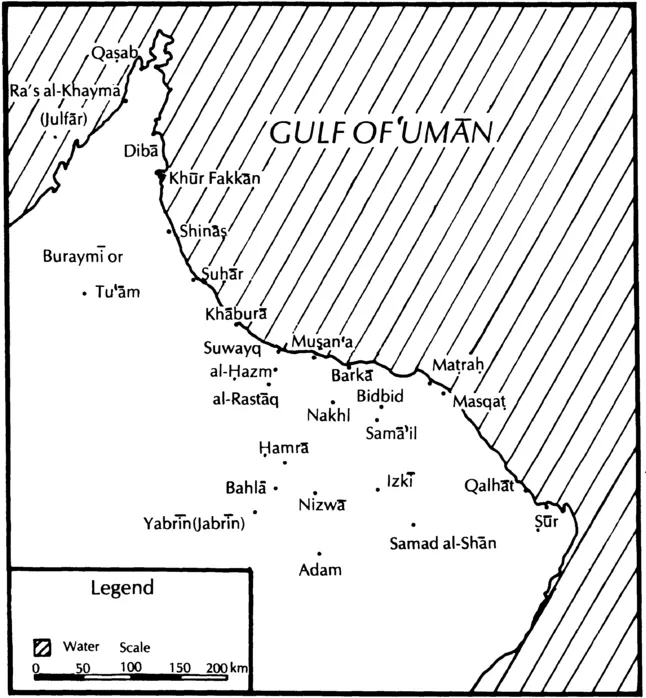

Map 2: towns and villages of ʿUmān and northern ʿUmān based on maps in Landen, Wilkinson and Skeet

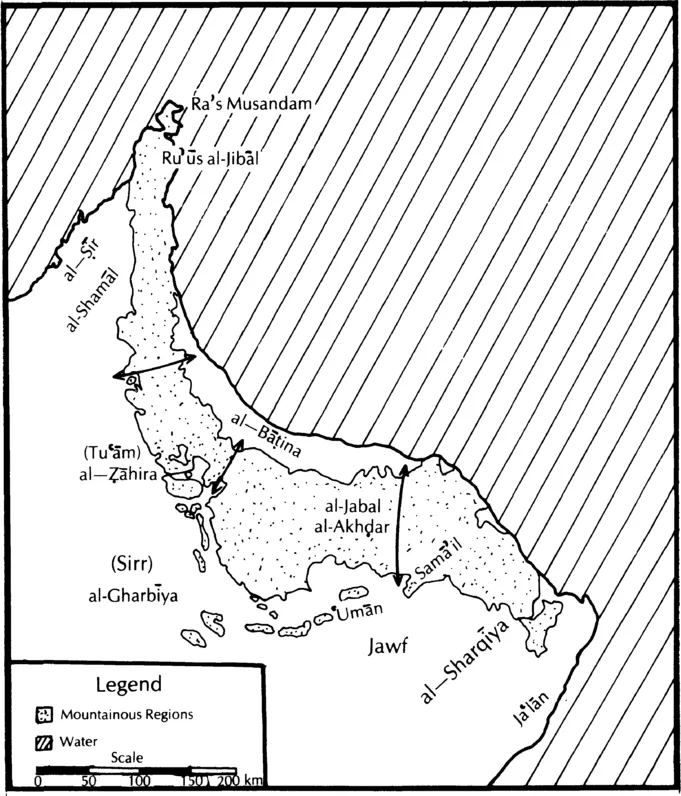

Map 3: mountainous regions and district names of ʿUmān and northern ʿUmān based on maps in Wilkinson and Landen

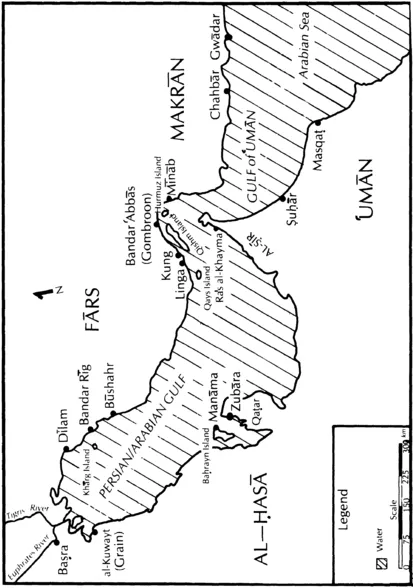

Map 4: Persian/Arabian Gulf based on Lorimer and Landen

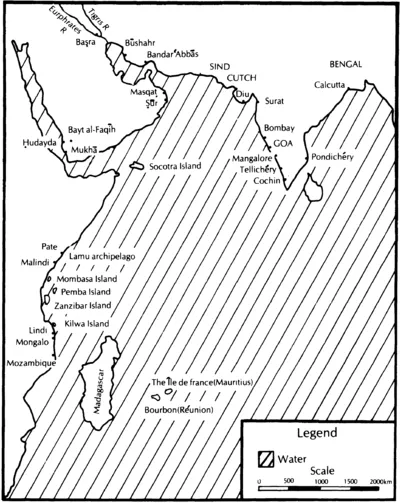

Map 5: Indian Ocean region

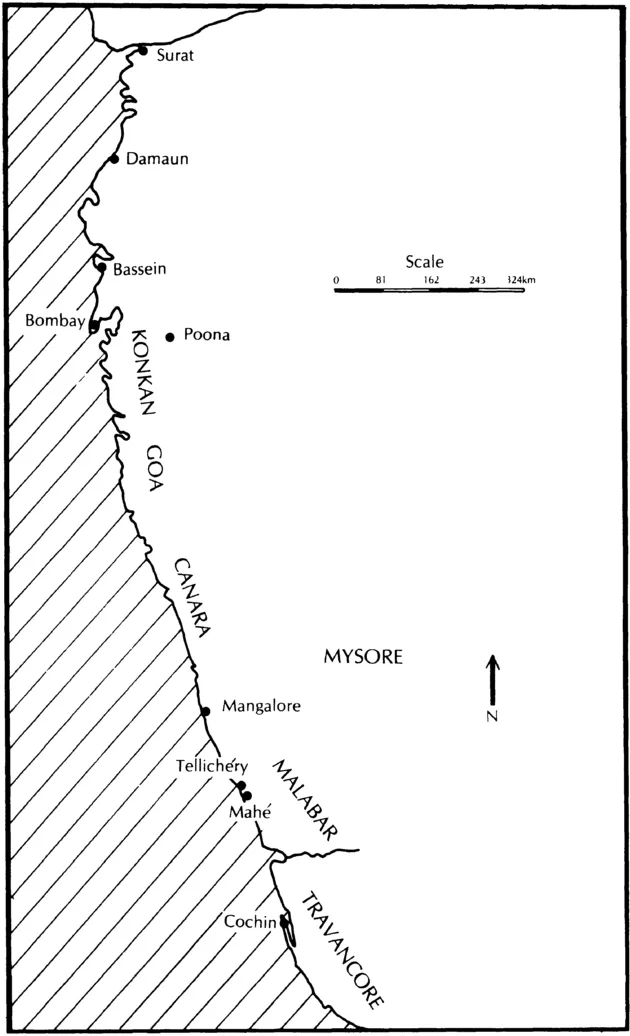

Map 6: western India, Surat to Cochin

![]()

Preface

During the second half of the eighteenth century, a religiously-sanctioned government in ʿUmân was replaced by a secular one and the secular government depended on new commercial wealth centered at Masqaţ. The purpose of this book is to examine how and why this happened. Most of the primary research falls between the election of the first Âl bû Saʿîdî imâm in 1749 and the death of the first successful secular Âl bû Saʿîdî ruler in 1804, dates provided by dynastic history but which correspond well with broader events.

The systematic study of the history of this part of the world in the early modern period is relatively new. It is still necessary to ask what happened (in the most obvious sense of that question) in order to offer convincing analytic arguments. The arguments have, therefore, been built on the detailed chronology worked out in chapters 3,4,6 and 9. The sources necessarily influence the approach. Internal history can trace the fluctuating relationships among tribal leaders, religious leaders, and members of the ruling family. External history concerns hostilities and overseas expansion, as well as the growing cohesiveness of yet another ʿUmânî social group, the maritime merchants. The constant challenge is to infer the interactions of internal and external events.

While chronology is an essential factor in the organization, there are topical considerations as well. The first two chapters attempt to convey an appreciation for ʿUmân's heritage, the complexity of which might surprise those whose knowledge of the country is confined to its oil production and strategic importance. They also provide perspective, because the eighteenth century is certainly not the only period for which transition in ʿUmân can be claimed. Another topic, mercantile history, is covered by chapters 5 and 10, which are intended to contrast two time periods—mid and late eighteenth century—in order to identify growth and change. These two chapters, along with chapter 7 on East Africa, emphasize the significance of ʿUmânî commerce in relation to the vast Indian Ocean region.

It is useful to view this particular fifty-year period of ʿUmânî history in a broad context. The eighteenth century in the Muslim world has generally been regarded as one of decline and there was indisputable decline in the three major Islamic empires, the Safavid, Mughal and Ottoman. But decline does not necessarily mean stagnation, and there is growing interest in finding and analyzing exceptions to the generalization.* Changes in the Indian Ocean and the Persian/Arabian Gulf qualify as such an exception and a basic change was a shift in commercial activity.

This milieu of shift and change helps explain ʿUmân's transition. While Ottoman Başra and southern Persia became increasingly less effective, new political entities emerged in eastern Arabia, notably ʿUtbî Kuwayt, Qaţar and Baḩrayn, the Wahhâbî province of al-Ḩasâ, and ʿAl bu Saʿîdî ʿUmân, all of them involved in the maritime carrying trade in one way or another. In East Africa, ʿUmânî Arabs replaced the Portuguese on several principal islands. What Mughal influence there had been along the western coast of India was now eroded, so individual merchants made their way under a merchant-prince like Ţîpû Sulţân or under the wing of the British Bombay government. Of all these new maritime ventures, the ʿUmânî was the most successful.

This book is intended primarily for those readers who have some knowledge of Islam and who have a specialized interest in ʿUmân itself, the Gulf or the Indian Ocean region. Topics of a more general and potentially comparative nature arise. The possibilities of mutual influence between tribal society and Islam is brought out in the ʿUmânî case with regard to the Ibâḑîya. Investigation into the relationship between hinterland and coast is limited by the eighteenth century sources but the problem is at least addressed for ʿUmân and for East Africa. And there is also the phenomenon of the mercantile impetus of the early modern period. Who controlled commerce and its profits? How did indigenous trade differ from that of European companies? Was 'worldly' trade incompatible with an Islamic form of government? Consideration of these questions in the pages that follow invites comparison with other times and places and also helps identify the factors which caused ʿUmân to alter so much during a fifty-year period.

![]()

Surely in the creation of the heavens and the earth;

In the alternation of night and day;

In the sailing of ships through the ocean for the profit of mankind;...

Here are signs for a people who understand.

the Qurʾân, II:164.

"No period of our hi story is better calculated to elucidate the powerful effects of commerce than the present."

H. Elmore, merchant ship's captain, India, c. 1796.

![]()

Chapter 1

Geographical and Historical Introduction

The term ₿Umân did not traditionally mean the same geographic region as it now does. Currently, the name is used as an abbreviation for the official state name which is, in its Anglicized form, the Sultanate of Oman. The modern state borders the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Kingdom of saʿudi Arabia, the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, and includes, not without difficulty, the province of Dhofar (al-Z̧afâr). The tip of the Musandam peninsula, Ruʿûs al-Jibâl, is also part of the state, separated from the rest of ʿUmân by the UAE (Map 1).

In the eighteenth century, the term ʿUmân was a more fluid one, referring most essentially to the heartland district around the town of Nizwâ (or Nazwâ). But it also referred to a larger area, that is, the following districts which are indicated on Map 3: al-Sharqîya; Sam̂ʿil (or Samâyil); the ʿUmân district just mentioned, extending into Jawf; al-Jabal al-akhḑar; al-Z̧âhira; al-Gharbîya (the last two are also called Tuʿâm and Sirr, respectively); and al-Bâţina, "inside" in relation to the surrounding western mountains.1 These district names were not precise but were used with a degree of uniformity that makes them meaningful. The area they comprise is what is meant by ₿Umân in this study and includes the entire coast from Şuḩâr to Şûr.2

Finally, there were regions in dispute throughout the eighteenth century. One was vaguely referred to as al-Shamâl, "the north". This included the coastal region northwest of Şuḩâr to Ruʿûs al-Jibâl, and al-Şîr province facing the Persian/Arab Gulf (hereafter referred to as the Gulf). This was not Ibâḑî territory in the eighteenth century but was traditionally claimed as part of ʿUmân. At the other extreme, in the southeast, was Jaʿlân, dominated by the Banî bû ʿAlî, Sunnîs who considered themselves independent of the imâmate and who were hostile toward the eighteenth century Âl bû saʿîdî rulers. However, the port of Şûr was under Āl bû saʿîdî control and marked the southeastern-most point of their influence.

The most striking geographical factors are the desert separating and isolating ʿUmân from the rest of the peninsula, the mountain range running through the country and the coastline facing toward the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, opening ʿumân to a maritime world. The mountain range is a more or less continuous curve whose two tips meet the sea and enclose the Bâţina. The northwestern portion of the range is called al-Ḩajar...