- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Eating Oil: Energy Use In Food Production

About this book

This book provides facts and figures to show how fast fossil fuel energy is being used up in the developed countries. It considers the problems of feeding the population of the developing countries to whom the expedient of using fossil fuel energy to boost food production is not available.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Eating Oil: Energy Use In Food Production by Maurice B. Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter One

The Nature of the Problem

How long can we go on eating oil? Before we try to answer this question, it is desirable to understand how and why we do eat it. If you live in a developed country like the United States or the United Kingdom, every mouthful of food you eat—unless you gather wild berries by the roadside—irrevocably consumes a finite amount of irreplaceable fossil fuel energy. This is because direct energy in the form of tractor fuel and indirect energy in the form of fertilizers are put into the operations of growing plant food and rearing animal food, and because energy is used in processing, distributing, and preparing food. Each of these stages uses some fossil fuel energy, so by the time the food reaches your table it has accumulated a fossil fuel energy “input.” (This is different from the energy that your body can get from food by eating it, which is commonly measured by the “calorie content” and which is the energy “output.”) We eat oil, therefore, by putting fossil fuel energy into the processes of food production, into the nation’s “food system.”

Why do we eat oil? Why is it necessary? The natural laws of thermodynamics decree that, to get more metabolically utilizable energy (that is, energy that can actually be used by your body) out of the food production system, you must either put more energy in or use the existing level of energy more efficiently, so as to achieve a better energy output:input ratio. The only sources of energy available to us are the direct energy of the sun, which plants utilize for us by the process of photosynthesis; the muscle power of men and animals, which is derived from the food they eat; and the energy of past sunshine, which is stored in fossil fuels. Wind and water power are indirect forms of solar energy because wind and rain result from temperature differences brought about by the sun. Ultimately, present or past sunshine is our sole source of energy with the exception of nuclear power.

The human body cannot thrive on sun and air alone; it also needs food. The body is, physically, a complicated coke boiler. It gets its energy by “burning” carbon to carbon dioxide, and the biochemistry of its digestive and respiratory systems is designed to turn the energy of this combustion into the metabolically utilizable form of adenosine triphosphate, which is the only fuel that will actually power our muscles. We get the carbon we need from the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, but we cannot use this directly; it is made available to us only through the mediation of photo-synthesis by the plants that provide our food and the food for our animals. Plants, unlike animals, possess the ability to take carbon dioxide from the air and to combine it with water from the soil by the action of sunlight to build the sugars, starches, fats, and proteins that we use for our nutrition. Likewise, we cannot use the carbon in fossil fuels directly for our bodily needs; we cannot actually eat oil. We can use it only to provide energy to increase the amounts of crops produced—that is, to increase the total amount of photosynthesis that determines the total amount of carbon dioxide “fixed” by plants and thus made available for our use as food. We do this by utilizing the fossil fuel energy, directly, in mechanical devices such as tractors or combine harvesters and, indirectly, to manufacture chemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides.

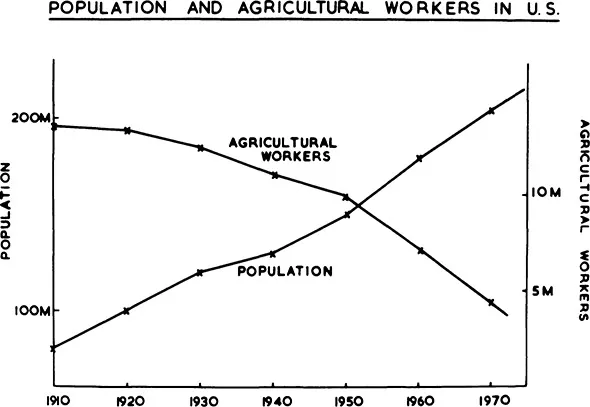

Why do we need to use fossil fuels at all in agriculture? Why cannot we just rely on the energy provided by photo-synthesis? Why cannot we, as some people advocate, grow all our food without using manufactured fertilizers or pesticides and by using animal and manpower rather than tractors? The answer is that we could if we were willing to reduce the population of the United States from the 220 million it is today to the 120 million it was in 1930. All that the U.S. government need do is draw up a list of the 100 million inhabitants who are to be allowed to starve and then order most of the remaining population back to work on the land. If the United States used for food production today only the amount of fossil fuel energy that it used in 1930 to feed the population, it would need about 76 million more ha of cropland and about 273 million more ha of farmland than are now being cultivated. This is an increase of about 60 percent over the present amounts of cropland and farmland. These extra amounts are simply not available: practically all land in the United States which can be cultivated is, in fact, being cultivated. Land is not, however, the only consideration. Even if the extra land were available, it would need 20 million agricultural workers—instead of the 4 million currently employed in the U.S.—to achieve 1976 output of food with 1930 input of energy. Similarly, for the United Kingdom to achieve 1976 food production with 1930 energy input would require that the amount of arable land now available be approximately doubled and the number of agricultural workers increased approximately fivefold. This is not possible.

Figure 1. Population and agricultural workers in U.S.

Source: U.S. government statistics.

The basic reason why we have to use fossil fuels in agriculture should now be quite clear: we have a large and growing population, of which only a small and decreasing percentage are engaged in agricultural production on a limited and dwindling amount of arable land.

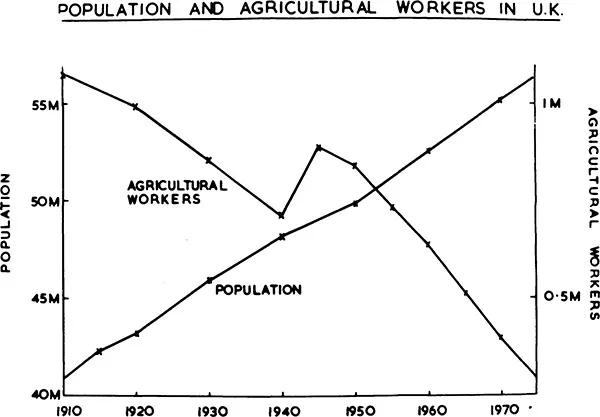

Figure 1 shows the upward trend of U.S. population and the downward trend of numbers of U.S. agricultural workers. Figure 2 shows the same thing for the United Kingdom. The total areas of the developed countries such as the United States and United Kingdom are fixed and their amounts of arable land are steadily decreasing as more homes, shopping plazas, freeways, airports, parking lots, etc., are built.

The key factor in the energy in agriculture problem is, therefore, the amount of arable land available per head of population. To understand the problem more clearly, let us consider primitive man. It is commonly believed that he had a hard time, working every minute to scratch together a frugal diet for himself and his family. It is clear that this was not so. The experts who have studied these matters tell us that only a small proportion of primitive man’s time was occupied with food gathering and that he had plenty of time to fight the neighbors, sing, dance, make love, draw pictures on the walls of his cave, develop a culture, and use his ingenuity to invent the things which enabled him to progress toward modern civilization. Primitive woman had less time available for such occupations as she was busy bearing and raising children, which is probably why, until recently, most occupations were male-dominated.

Figure 2. Population and agricultural workers in U.K.

Source: U.K. government statistics.

Modern studies (Lee 1969) of the Kung bushmen, a primitive tribe still living in Africa, have shown that they

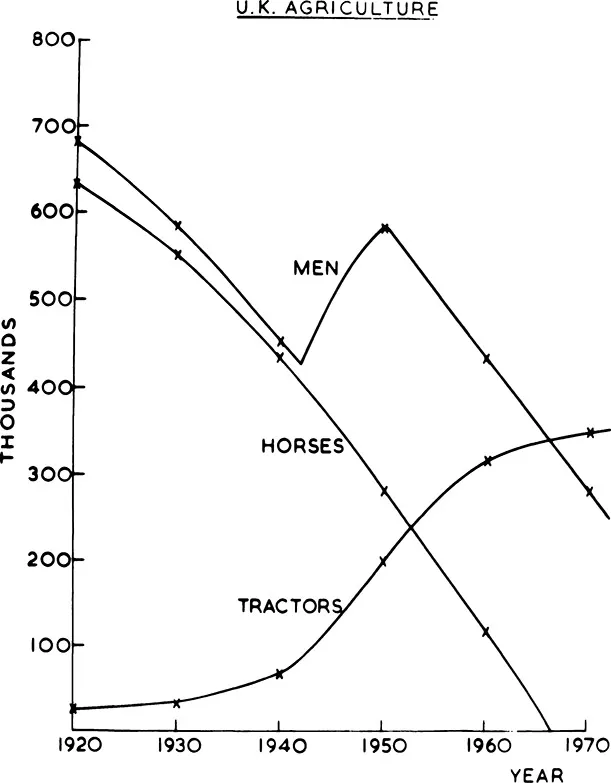

Figure 3. U.K. agriculture.

Source: U.K. government statistics.

provide themselves with a varied high-protein diet based on nuts, animals, and twenty different types of vegetables by food gathe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Photographs

- Preface

- Notes on Units

- 1. The Nature of the Problem

- 2. Energy in Primary Agricultural Production

- 3. Energy in Food Processing, Distribution, and Preparation

- 4. Possible Ways of Saving Energy: General Considerations

- 5. Possible Ways of Saving Energy: Agriculture

- 6. Possible Ways of Saving Energy: Food Processing, Distribution, and Preparation

- 7. Feeding the World’s Population

- 8. The Final Reckoning

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- References and Further Reading

- Index