- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forensic DNA Technology

About this book

Forensic DNA Technology examines the legal and scientific issues relating to the implementation of DNA print technology in both the crime laboratory and the courtroom. Chapters have been written by many of the country's leading experts and trace the underlying theory and historical development of this technology, as well as the methodology utilized in the Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) techniques. The effect of environmental contaminants on the evidence and the statistical analysis of population genetics data as it relates to the potential of this technology for individualizing the donor of the questioned sample are also addressed. Other topics include the proposed guidelines for using this technology in the crime laboratory, the perspective of the prosecution and the defense, the legal standards for determining the admissibility and weight of such evidence at trial. Finally, the issues of validation and the standards for interpretation of autoradiograms are brought into focus in a detailed study of actual case work. Forensic scientists, prosecuting attorneys, defense attorneys, libraries, and all scientists working with DNA technology should consider this a "must have" book.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Milestones in the Development of DNA Technology

J.A. Witkowski Ph.D

Introduction

DNA technology is having an increasing impact on our daily lives. The availability of DNA diagnosis for an ever-increasing number of human inherited disorders has brought significant benefits to families afflicted by these diseases.1 DNA technology is leading the fight against AIDS2 and recombinant DNA techniques may result in “tailor-made” drugs and other therapeutic agents.3,4 However, one of the most spectacular, and certainly one of the most publicized, applications of DNA technology involves so-called DNA fingerprinting.5,6 The mystique of DNA, together with the apparently infallible identifications that result, is proving to be a potent combination when the evidence analysis is presented in court. It is difficult under these circumstances to realize that DNA typing is the result of a “basic” research project that in itself was based on experiments and theories stretching back over the past 50 years. In this brief introduction DNA typing will be set in its scientific context and some of the milestones in the development of molecular biology will be described.7

The Dawn of Molecular Biology

A good year to begin is 1938, the year in which the phrase molecular biology was first used, or at least first appeared in print. Warren Weaver, director of the Rockefeller Foundation, used it in his annual report to describe a new field of research, one that was “... beginning to uncover many of the secrets concerning the ultimate units of the living cell . . .”.8 It was in large part the Rockefeller Foundation, through the advocacy of Weaver, that nurtured the new field by providing support for the x-ray crystallography of biological molecules.9 This was a particularly British science and owed its existence to the strong British tradition of x-ray crystallography developed by W. H. Bragg and his son W. L. Bragg, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics jointly in 1915 (W. L. Bragg was only 25, the youngest person ever to win the Nobel Prize).

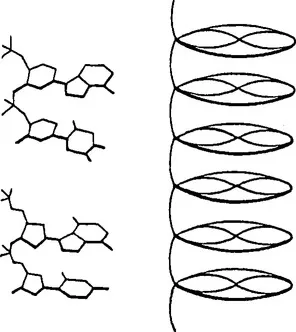

1938 was also the year in which Bill Astbury and Florence Bell, at the University of Leeds in England, published the first important x-ray crystal-lographic study of DNA.10 Astbury (see Figure 1), a student of W. L. Bragg, had worked on keratins, the major constituents of wool, because Leeds had a large weaving industry. He showed that the α-form of keratin was changed into an elongated β-form when wool was stretched, an impressive demonstration of the power of x-ray crystallography in analyzing the behavior of biological molecules. Astbury was interested in the functional significance of the structures of biological molecules, and he began to analyze all sorts of natural fibers.” He and Bell examined a dried film of DNA and concluded that the nucleotides were arranged one above the other at right angles to the fiber axis,10 (Figure 2). Astbury and Bell were delighted to find that the distance between successive nucleotides in their structure was 3.4 Â, almost identical with the spacing of 3.3 Â between successive amino acids in a polypeptide chain. The experimental results seemed to be clear evidence that there was an interaction between proteins and nucleic acids, the latter acting as a framework for the former. In fact, this correspondence between nucleotide and amino acid spacing was a numerological coincidence and the “pile of pennies” model was wrong.9,12

DNA As The Molecule of Life

Astbury seems to have been interested in DNA simply because it was another natural fiber he could analyze. The first convincing demonstration that DNA did something interesting biologically came in 1944 when Avery, Macleod, and McCarty showed that DNA could act as a carrier of hereditary information.13,14 Up to that time DNA had been dismissed from such a role because biochemical analyses purported to show that the four nucleotides were present in equimolar amounts, and it was assumed that DNA was a polymer of a simple four-nucleotide repeated unit.9,15 It was clear that proteins with their 23 amino acids were much more complicated and a priori more likely to be the hereditary material. Avery et al. showed otherwise, using the bacterium Pneumococcus. Pneumococcus type II normally forms smooth colonies when grown on agar, but Avery et al. isolated a variant that formed rough colonies. They were able to transform this rough variant into the smooth form of Pneumococcus III using DNA purified from the smooth form of Pneumococcus III. DNA alone was able to transfer a genetic character and, in addition, the transformed bacteria remained stable through successive generations. There has since been an interesting debate as to whether Avery et al.’s paper was neglected by the scientific community.14-17 In retrospect Avery’s data is convincing evidence that DNA and not protein is the genetic material, but at the time this conclusion was not widely accepted. However, it is clear that this study of Avery et al. is one of the classics of modern biology and one that should have won the Nobel Prize.

Figure 1 W. T. Astbury, the British “bulldog” of x-ray crystallography, who with Florence Bell, made the first detailed analysis of DNA. Reproduced by permission of the Department of Textile Physics, University of Leeds, U.K.

Figure 2Bell and Astbury’s “pile-of-pennies” model for DNA. “Alternative formulae for a pair of (purine and pyrimidine) nucleotides” are shown in the left part of the figure and “the idea is that of a very tall column of discs with a linking rod down one side” (right part of figure). The nucleotides project out at right angles to the axis of the single helix, one above another. Reproduced by permission from Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 6:109-118, 1938.

DNA as The Double Helix

This part of the story hardly needs telling, having been the subject of a number of books and a television play.9,17,19 What does need emphasizing is that it was not a question of luck, although like almost all scientific discoveries, elements of luck were involved. Rather, Watson and Crick, by using a combination of a great deal of shrewd and inspired thinking, together with x-ray crystallographic data from Rosalind Franklin21 and Maurice Wilkins, derived a structure for DNA that, once seen, had to be right (Figure 3). The crux of the solution was the realization that nucleotides could pair with each other such that an adenine (A) paired with a thymidine (T), and a guanidine (G) paired with a cytidine (C) (Figure 4).22 Base pairing is the essential characteristic of the DNA molecule that permits all the manipulations of recombinant DNA and DNA typing.

Base pairing was first exploited experimentally in 1960 when it was shown that the two strands of the DNA double helix could be separated and that these separated strands would then hybridize to RNA molecules.23-25 The importance of this discovery was the demonstration that the base pairing was sufficiently precise that the single DNA strand hybridized specifically with its complementary RNA molecule. Hybridization in solution was used extensively to analyze DNA molecules, but by the mid-1970s a set of procedures, including analysis of DNA fragments by electrophoresis in agarose gels and ethidium bromide staining,26 Southern blotting,27 and “nick-translation” to produce radioactive probes,28 had been developed for hybridization studies. Hybridization in solution is still a major tool in determining the degree of similarity between DNA molecules in studies of gene evolution.29

The Enzymes

At the same time that studies of RNA, protein synthes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- About the Editors

- About The Authors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Milestones in the Development of DNA Technology

- 2 An Introduction to DNA Structure and Genome Organization

- 3 Analysts of Forensic DNA Samples by Single Locus VNTR Probes

- 4 Population Genetics of Hypervariable Human DNA

- 5 The Polymerase Chain Reaction

- 6 Validation with Regard to Environmental Insults of the RFLP Procedure for Forensic Purposes

- 7 The Meaning of a Match

- 8 General Admissibility Considerations For DNA Typing Evidence

- 9 DNA Testing in Criminal Cases

- 10 Managing The Implementation and Use of DNA Typing in the Crime Laboratory

- Glossary

- General Index

- Index of Cited Cases

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Forensic DNA Technology by Mark A. Farley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Forensic Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.