1

Tourist Shopping Opportunities

Placing Tourist Shopping Villages in a Larger Context

INTRODUCTION

Shopping is the core of consumption and retailing the emblem of a consumer society (Timothy 2005). The primary goal of retailing is to encourage people to shop and purchase merchandise and services. As shopping is one of the oldest and most common activities associated with travel, it might be expected that the relationship between tourism, retailing and shopping should be of concern to tourism academics. Perhaps surprisingly, and however obvious the relationship would appear, an analysis of shopping has not been at the forefront of tourism research (Coles 2004b). While the existing tourism academic interest may be limited, shopping is becoming increasingly important to tourism both in terms of the actual consumption of goods purchased and as a source of enjoyment and satisfaction. Shopping stimulated by visitors outside of the local region has an important economic impact on host communities as well as being a key attraction for visitors (Asgary, et al. 1997; Jackson 1996).

The shopping districts of the world, which attract tourists and beguile locals, form an impressive array of high status locations. Guidebooks frequently highlight elite districts known for their shopping. The street names have the aroma of money. Rodeo Drive, Fifth Avenue, the Champs Elysees, Oxford Street, Via Veneto, Orchard Road and the Bund symbolise prestigious shopping opportunities in their respective cities. Many may gawk at their wares but only the affluent are truly at home inside the palaces of contemporary consumerism (Ritzer 1999). Importantly, shopping in many other forms also attracts tourists. There are duty free shops and there are outlet stores. For some tourists local markets are attractive while for a few others black markets appeal. Beyond the cities and the airports and reaching into the countryside a special form of tourist shopping can also be identified. High Street, Bridge Street, Gorge Road and Mountain Drive may not have quite the cache of the big city thoroughfares but the shop lined roads of many small villages are also a tourist attraction. These kinds of precincts, and the people who shop, work and live there, form the subject matter of this book.

In essence this volume seeks to examine in detail the phenomenon of Tourist Shopping Villages (TSVs), which are defined as:

Tourist shopping expenditure represents a source of funding for both the private and public sector and this income source can revitalise retail areas, townscapes and streetscapes (Turner and Reisinger 2001). Tourist shopping villages are places of entertainment and leisure and they can also be pathways for local communities to share in the economic benefits of tourism. There are many interest groups affected by, and keen to understand, tourist shopping villages. These groups include but extend beyond academics and tourism analysts to those keen to develop tourism. Government officials and civic leaders may wish to attend to the development of shopping villages as a consideration in their policy initiatives. Of course individual entrepreneurs and retailers seek satisfactory returns while local community residents may identify a suite of amenity benefits.

Tourist shopping villages are also a fertile academic ground for analysing the planning and delivery of contemporary tourist experiences. It can be argued that much tourism research and theory has been focussed on understanding the nature and outcomes of tourist experiences. Recent attention has been focussed on trying to map out conceptual models to explain the nature of tourist experiences (Moscardo 2008c; Uriely 2005).

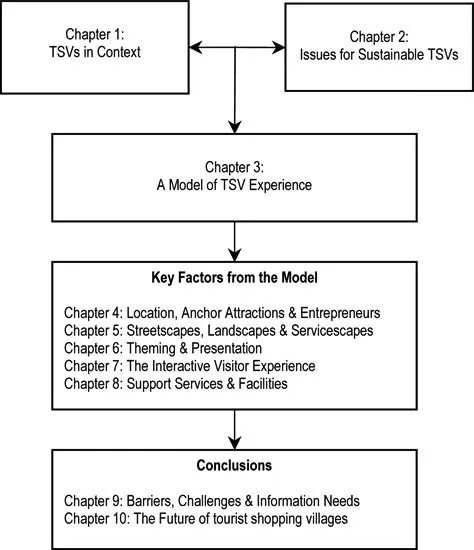

The present book therefore has two main aims. The first is to use new research and existing literature to critically examine tourist shopping villages in order to understand how their performance can be enhanced for multiple stakeholders. The second aim is to use this context to examine in more detail key elements of tourist experiences and thus contribute to the growing interest, both within and outside tourism, in developing a theory of tourist experience. Figure 1.1 provides an overview of the structure of the book.

This first chapter will place tourist shopping villages in a wider context of tourist shopping opportunities and forms and introduce the concept of tourist shopping villages. Chapter 2 will examine tourist shopping villages in more detail with a focus on the sustainability issues they face in terms of impacts and changes to destinations and their residents. The third chapter will provide an overview of both recreational and tourist shopping and identify a number of concepts and theories that could be

used to understand this phenomenon. This chapter will also introduce a TSV Visitor Experience Model. The detail in this chapter will provide an extensive rationale explaining the choice and selection of sets of factors to be considered in the subsequent chapters. At this point in the volume it is simplest to record the layout of the subsequent chapter structure and to await its justification at a later point in the sequence of work. Based on the model in Chapter 3, Chapters 4 to 8 will explore dimensions of this model in more detail using a variety of research evidence and literature to develop a more detailed understanding of the nature of tourist experiences in these shopping villages. In many instances these chapters will present case studies of villages drawn from a multi-country sample which the researchers have visited and studied. The penultimate chapter will highlight an array of research futures while the final chapter will reflect on the nature of the tourist shopping village experience and review likely trends into the future.

TOURIST SHOPPING: AN OVERVIEW

The current tourist interest in shopping can be explained by an increasing demand for leisure activities in general and the search for new experiences in particular. As a consequence, shopping areas are now being developed as a core element in many tourist products (Jansen-Verbeke 2000). Given this growing demand for shopping by tourists, destinations have begun initiating major shopping promotional campaigns and have often adopted retailing and tourist shopping as official policies in their tourism development efforts. In some cases, overall shopping policies have been altered considerably as a result of tourism. Extended trading hours in tourism areas is an example of such an influence (Timothy 2005).

The growing importance of shopping as a leisure and tourism activity results from an increasingly materialistic and consumption oriented society in which the act of shopping is not only utilitarian, with a focus on acquiring necessities for daily needs, but has become a part of the touristic experience in which clothing, souvenirs, artworks and handicrafts are purchased as reminders of travel experiences (Michalkó 2001; Timothy 2005; Timothy and Butler 1995). Although the tourism marketing literature discusses the importance of tourist retail expenditures to local economies, few studies are actually concerned with retailing to the tourist segment (Heung and Cheng 2000). Turner and Reisinger (2001) argue that tourists form a different retailing segment. In this view tourists place importance on different products and product attributes to those sought by other groups. Shopping may have its own inherent promotional power for tourist destinations since items purchased during travel, as well as photos and videos, may entice other visitors (Kim and Littrell 2001). Backstrom (2006) argues that research must acknowledge recreational shopping as a multifaceted activity since it may be performed in different ways in various settings and embody different types of consumer meanings. She also emphasises that the multiplicity of the individuals engaged in recreational shopping needs to be studied in more refined terms. The core theme, which integrates many of these studies, is that tourist shopping is an important but understudied phenomenon which is somewhat different from other forms of retail activity.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SHOPPING AS A TOURIST ACTIVITY

The importance of shopping as a tourist activity can be seen in several statistical indicators. A consideration of expenditure, levels of participation by tourists and day-trippers and ratings of shopping as a reason for travel and/or destination choice all attest to the importance of shopping in multiple destinations. Tourism Australia, for example, provides statistics for 2009 indicating that expenditure on shopping, gifts and souvenirs for domestic day visitors was more than $3 million, which is the highest expenditure of any category. A further $2.5 million was spent by domestic visitors on overnight trips (Tourism Research Australia 2009b). The average shopping expenditure for international visitors was $312 per trip (Tourism Research Australia 2009a). Statistics provided by other tourism marketing organisations provide a similar picture. In Poland the figure is 24 per cent reflecting higher levels of cross-border shopping from neighbouring countries for cheaper goods, while the figure for the United Kingdom is 20 per cent (Institute of Tourism Poland 2008). In New Zealand gifts, souvenirs and other shopping make up 14 per cent of domestic tourist expenditure and 30 per cent of day-tripper expenditure (Cooper and Hall 2005).

These expenditure figures are consistent with the levels of participation in shopping as an activity reported by tourists in various studies. In a survey of more than 1600 international and domestic tourists to the North Queensland region of Australia, 62 per cent reported engaging in general shopping and 48 per cent reported shopping for local arts and crafts (Moscardo 2004). Robertson and Fennell (2007) report that shopping is one of the United Kingdom’s most popular leisure activities. From a tourism perspective, some 16 percent of day trips in the UK are to go on non-regular, non-convenience shopping trips, which is the third most frequent activity after eating out or visiting friends and relatives. The focus of Robertson and Fennell’s (2007) research was on regional shopping centres and they reported that 42 percent of visitors to Essex were planning to visit shopping centres, making them nearly twice as popular as seaside attractions which were listed by 26 per cent of the sample.

A report from the Travel Industry Association (2001) indicates that shopping was the most popular activity among domestic travellers. Shopping was included in 30 per cent of domestic trips. Similarly, and based on an analysis of the Travel Activities and Motivations Survey, the Ontario Ministry of Tourism (2007c) in Canada reports that shopping and dining are Canadian travellers’ most popular activities. A further detailed component of the report reveals that shopping at the destination, although not usually a trip-motivator, is an important activity for 66 per cent of travellers from the U.S. and 70 per cent from Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Tourism 2007b). In both cases shopping or browsing in clothing, shoe and jewellery stores was the most popular style of behaviour reported.

Overall, 16 per cent of American travellers and 15 per cent of Ontario travellers rated “great shopping opportunities” as a highly important condition when choosing a pleasure destination (Ontario Ministry of Tourism 2007d). The Ontario Ministry of Tourism (2007b), conclude that, while shopping is not frequently a trip-motivator, even for those who engage in shopping, it remains an important activity that many travellers expect to engage in while travelling. As such, it is not only the actual shopping opportunities that a destination offers, but also the perception of a destination’s shopping opportunities that is important to travellers. According to more academic analyses shopping is among the most common and enjoyable activities undertaken by people on holiday and, in many cases, it provides a major attraction and basic motivation for travel (Jansen-Verbeke 2000; Timothy 2005). The core of this view is that tourists search for unique shopping and leisure experiences to define and structure their day trips. This brief review of evidence on the extent and economic importance of shopping indicates not only that this is a substantial component of tourism, but that there are also different types of shopping within the overall category of tourist shopping.

TYPES OF TOURIST SHOPPING

One way to improve our understanding of tourist shopping is to develop a classification scheme for different types of shopping. In the reminder of this chapter a scheme is developed following Hall’s (2005) approach to tourism systems. The scheme uses three dimensions of tourist shopping. The first component to be considered is a temporal dimension based on when in the holiday or travel experience the shopping takes place. Secondly, shopping has a spatial dimension and the incorporation of this component helps formulate the approach. The third and final dimension to be considered is psychological and here traveller motivation and interests are important.

TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL DIMENSIONS OF TOURIST SHOPPING

In terms of the temporal dimensions of travel Hall (20...