eBook - ePub

Immunotherapy of Diabetes and Selected Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmune 8

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This important text will be the first devoted to a detailed analysis of immunotherapy as it applies to Type I diabetes and the pathogenesis and therapy of other specific autoimmune diseases (including uveitis, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, Cogan's syndrome, Graves' ophthalmopathy, and gonadal disorders).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immunotherapy of Diabetes and Selected Autoimmune Diseases by George S. Eisenbarth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Endocrinology & Metabolism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Immunopathogenesis of Type I Diabetes Mellitus

Richard J. Keller and George S. Eisenbarth

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- I. Introduction

- II. Disease Course

- III. Histologic Studies

- IV. Genetics

- V. Environmental Factors

- A. Viruses

- VI. Prediction of Type I Diabetes

- A. Islet Antibodies

- B. What is the Target Antigen on the Beta Cell?

- C. Insulin Autoantibodies

- D. Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IVGTT)

- E. Dual Parameter Model

- F. Other Parameters

- VII. Potential Mechanisms of Beta Cell Destruction

- A. Cytotoxic Antibodies

- B. Cytotoxic T Cells

- C. Killer Cells

- D. Natural Killer Cells

- E. Abnormalities in Circulating T Lymphocytes

- F. Monokines and Lymphokines

- G. MHC Class II Expression

- H. Free Radicals

- VIII. Considerations for Timing of Immunotherapy

- Acknowledgments

- References

I. Introduction

Type I diabetes mellitus, or insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), is a common endocrinologie disorder (approximately 3/1,000 cumulative incidence), carrying a significant morbidity and mortality. There is now substantial evidence that Type I diabetes is a genetically determined chronic autoimmune disease, with a long subclinical prodromal phase during which beta cell destruction is occurring.1-7 As discussed in detail in other chapters, the prevention of this disease by immunotherapy has entered the stage of clinical trials. In this chapter, we will summarize our current concepts concerning the pathogenesis and natural history of Type I diabetes. It is this natural history of disease which both limits and provides unique opportunities for immunointervention.

II. Disease Course

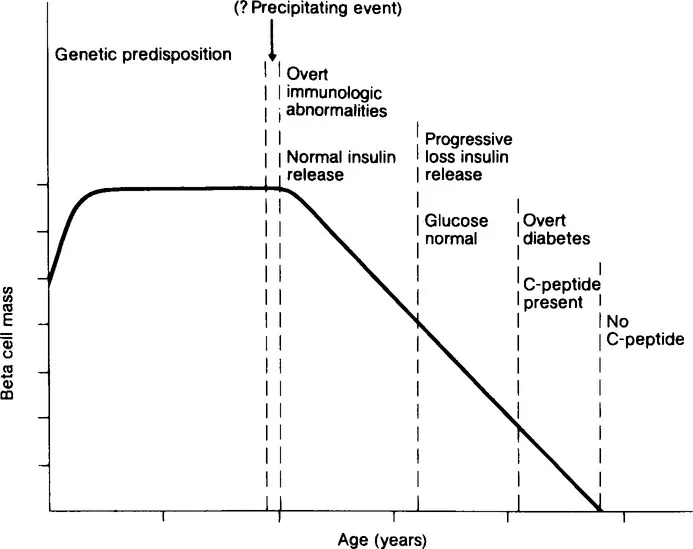

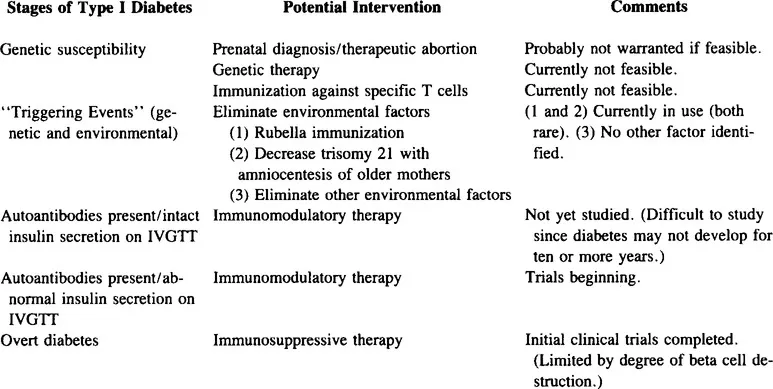

We view the development of Type I diabetes as a process involving several stages beginning with genetic susceptibility and ending with complete beta cell destruction (Figure 1). Each of these stages provides a window in time during which immunotherapy may be effective in preventing disease (Table 1). First, there appears to be an obligatory genetic predisposition. A precipitating event, either mutational or environmental, may then trigger the progressive immunologic destruction of beta cells. It is possible that many different precipitating events (e.g., viruses, chemicals) play a role in initiating beta cell damage (e.g., by turning off natural immunosuppression or by antigen mimicry), but once the immunologic destruction of beta cells reaches a certain threshold, as evidenced by high titers of cytoplasmic islet cell antibodies, the process appears to continue to overt diabetes.

After “the” precipitating event, there is a variable period of time during which there is normal insulin release, but when one can detect immunologic abnormalities (high titer cytoplasmic islet cell antibodies [ICA], insulin autoantibodies [IAA], la + T cells). During this initial period of immunologic abnormalities, insulin secretion is normal.

Once a critical number of beta cells is destroyed, there is progressive loss of insulin release, yet euglycemia is temporarily maintained. Loss of first phase insulin secretion following intravenous glucose is the first metabolic abnormality we have detected prior to overt diabetes.8 Finally, overt diabetes ensues, often made evident during a period of stress (e.g., infection) probably secondary to an augmented insulin requirement. The pancreas still makes some insulin at this point, reflected by the presence of C-peptide (Connecting peptide of proinsulin) secretion. After diagnosis, there is a variable “honeymoon” period when the patient may not require insulin. This period is associated with improved insulin secretion and improved insulin responsiveness due to better metabolic control. Finally, the residual beta cells are completely destroyed leading to absent endogenous insulin and C-peptide secretion.

III. Histologic Studies

The earliest evidence for an autoimmune basis of Type I diabetes came from histologic studies of the diabetic pancreas.9,10 The normal pancreas has islets containing insulin-secreting beta cells, glucagon-secreting alpha cells, somatostatin-secreting delta cells, and PP cells secreting pancreatic polypeptide. Most beta cells are located in the center of the islet, and the other three cell types are organized around the islet periphery.

Insulitis, characterized by a mononuclear islet infiltrate especially rich in T cells, is associated with Type I diabetes.11 Insulitis is reportedly present only in islets which still contain beta cells. At the time of diagnosis, only 10% of beta cell mass remains.11 Within the diabetic pancreas, there are “pseudoatrophic” islets devoid of beta cells or inflammatory cells, but containing normal alpha, delta, and PP cells. Other islets have active insulitis, and yet others are completely intact. There are also some areas of beta cell regeneration. The histology is analogous to a plaque assay in microbiology, with only some islets affected, and those which are affected displaying various stages of beta cell destruction. One hypothesis to account for such plaquing is that a rare activated T cell in circulation occasionally seeds an individual islet to initiate the inflammatory process. From the histology one can hypothesize that the development of diabetes is a chronic process with gradual and progressive beta cell loss. It is not until several years after diagnosis that all the beta cells are destroyed, with the islets free of inflammation.11

FIGURE 1. Proposed stages in the development of Type I diabetes (From Eisenbarth, G. S., Autoimmune beta cell insufficiency, Triangle, Sandoz J. Med. Sei., 23(3/4), 111, 1984. Copyright Sandoz Ltd., Basle, Switzerland.

TABLE 1

Potential Stages of Intervention

Potential Stages of Intervention

Bottazzo12 recently had the opportunity to examine the pancreas of a 12-year-old child who died of diabetic ketoacidosis at presentation. He reports that 24% of the islets had insulitis. Most of the infiltrating lymphocytes were Ts/C cells, but TH and natural killer (NK) cells were also present. Most of the T cells were “activated”, with la and interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor staining. Complement-fixing antibodies were found within the islets and on the surface of some cells. There was an increase in class I HLA antigen expression (HLA-A, B, C) on the remaining beta cells. In addition, some of the beta cells reportedly expressed class II antigens (HLA-DR, DQ, DP), whereas none of the alpha or delta cells displayed class II antigens. However, with the section utilized, it is not possible to distinguish beta cells expressing class II antigens from beta cells engulfed by class II antigen positive macrophages. Such engulfed beta cells appear to account for the class II antigen-stained islet cells in animal models of diabetes. In Bottazzo’s12 study, the capillary endothelial cells were also noted to have significant class II expression. Foulis and co-workers,2a have recently described hyperexpression of class I antigens at the onset of diabetes in islets with residual beta cells. Alpha-interferon was also found within these islets. They hypothesize that these changes may be secondary to chronic viral infection of the islets.

Soon after pancreatic transplantation between identical twins discordant for Type I diabetes, Sutherland13 found a recurrence of insulitis causing overt diabetes in the initially normal transplanted pancreas, again supporting an immunologic etiology for Type I diabetes. Notably, he did not find class II expression on the recipient beta cells despite their rapid destruction. Sutherland’s study suggests that once the autoimmune process is activated, the destruction of “normal islets” can be extremely rapid.

IV. Genetics

Of patients with Type I diabetes, 90 to 95% are DR3 and/or DR4+ compared to 50 to 60% of the general Caucasian population, and approximately 60% of patients with diabetes express both DR3 and DR4.14,15 DR4 is reportedly more common in younger diabetic individuals. There is some evidence that diabetes associated with DR3 may be different from the DR4-associated disease, though the majority of patients express both histocompatibility alleles. The DR3+ patients may have a slower disease course, with retention of C-peptide for longer periods after diagnosis.16 DR4+ diabetic individuals reportedly display a more rapid loss of beta cell mass after diagnosis, and are less likely to have a prolonged honeymoon period. DR3, which is in linkage disequilibrium with HLA B8, is associated with Type I diabetes only in Caucasians and American Blacks. DR4, which is in linkage disequilibrium with HLA B15, is associated with Type I diabetes in all ethnic groups studied. There are also certain HLA alleles, most notably DR2, which are decreased in patients with Type I diabetes.17,18 With analysis of DNA restric...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- The Editor

- Contributors

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Immunopathogenesis of Type I Diabetes Mellitus

- Chapter 2 Immunogenetics and Immunopathogenesis of the NOD Mouse

- Chapter 3 Immunotherapy of the BB Rat

- Chapter 4 Immunotherapy of the NOD Mouse

- Chapter 5 Cyclosporine for Type I Diabetes: Lessons from First Clinical Trials and New Perspectives

- Chapter 6 Immune Interventional Studies in Type I Diabetes: Summary of the London (Canada) and Canadian-European Experience

- Chapter 7 Azathioprine Immunotherapy for Insulin-Dependent Diabetes: U.S. Trials

- Chapter 8 Azathioprine Immunotherapy: Australian Trials

- Chapter 9 Immunomodulatory Drugs in Type I Diabetes

- Chapter 10 Immunotherapy of Uveitis

- Chapter 11 Immunotherapy of Graves’ Eye Disease

- Chapter 12 Immunopathogenesis and Therapy of Gonadal Disorders and Infertility

- Chapter 13 Pathogenesis and Immunotherapy of Cogan’s Syndrome

- Chapter 14 Immunotherapeutic Approaches for Multiple Sclerosis

- Chapter 15 Myasthenia Gravis

- Chapter 16 Toward More Selective Therapies to Block Autoimmunity

- Index