![]()

1

The first steps

Since the early 1990s, the idea of ‘exporting democracy’ under the guise of ‘good governance’ has been the major point of reference for the work of international agencies in developing countries. It is not limited to theory but amounts to a major social phenomenon. In its name, thousands of people are employed, hundreds of millions of dollars are channelled each year to ‘developing’ countries, local and international realities are transformed. What is this governance which, since the mid-1990s, has become a central element of political expression at international and national levels, and indeed is used to guide the functioning of authority in large companies? Official texts at the United Nations and the World Bank, among other international institutions, try to give it a practical definition. This supposedly new notion denotes ‘an economic, political and administrative exercise with the aim of managing a country’s affairs at every level’ (UNDP 1998:3) and over the last ten years a substantial corpus of guidelines has been developed in its name by the major international development agencies.1

At the heart of this new body of work, the aim of the international agencies is to aid local NGOs in developing countries on the grounds that NGOs are (supposedly) representative of civil society and provide a counterbalance to the power of governments. Assistance to local NGOs, perceived as a guarantee of good governance, is now accepted by bilateral (e.g., USAID) and multilateral organizations (the World Bank, UNICEF, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the World Health Organization (WHO), and others) as relevant to what they see as a new ethics of development.

Supporting local NGOs rather than the state may seem paradoxical: development agencies are the creation of governments and need the agreement of a given country’s government before they can establish their aid projects there. This characteristic is the basis of much criticism of these agencies, accused of being ‘in the pockets’ of governments. Supporting local NGOs within a framework of promoting good governance may, in addition, be the latest manifestation of an older concern with supporting the ownership of projects by the populations concerned. A talisman of international development organizations, this preoccupation has actually taken many forms during the past few decades, such as the struggle for ‘participation’ of local actors as part of their self-development, and respect for their ‘traditions’.

It would seem, however, that the meaning and practices surrounding the notion of good governance actually stem from a new ‘humanitarian ideology’ rising from the ruins of Third World-ism. To analyse it, I chose to look at a specific area of this supposedly universal support for good governance in countries of the South, newly expanded towards the East: the area of HIV prevention. There are two reasons for this choice. The first is that this epidemic is both a revealing indicator and a factor of social change for modern societies. The second reason is that the NGOs involved in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic in North America and Europe are often engaged in all sorts of battles around sexuality, inequality of the sexes, the pharmaceutical industry, the politics of the market or public health reform. The policy of good governance encourages development agencies to present this phenomenon as typical of the involvement of local NGOs.

New York, New York

This story begins during the winter of 1994 in New York, on the seventh floor of the International Development Organization (IDO) headquarters. It is a composite world, partly a mirror of American big city life but also a specific environment where actors’ behaviour is set against the norms and culture of an international institution. I came originally for a short-term internship that soon turned into a fixed-term post, spending over a year in the office that oversees development aid in countries of the former USSR.

In line with New York corporate lifestyle everyone’s place in IDO’s hierarchy was discernible by the office space allocated to them. For the Chiefs, an office with outward-facing windows, the number of windows being in direct proportion to the hierarchical status of the beneficiary; for others, an office with artificial lighting facing the corridor. During my first few days, confined to a cubicle, I began to have problems with my eyesight. Worried, I consulted an ophthalmologist, and requested office space with natural daylight. I was given one, but in the process attracted considerable hostility from an Assistant Chief who had waited years before obtaining such a ‘privilege’. This hostility took a while for me to understand. A few months later, less naïve, I noticed a team of building maintenance workers in the corridors, and this time immediately understood what was going on: they had come to shift the dividing walls between two offices which until then had been of similar size, each one having two windows. The occupant of the office on the left had recently been promoted and therefore merited three windows; hence the repositioning of the dividing wall, taking one of the windows from her now lower-ranked neighbour to the right.

The institution

Created after the Second World War, IDO is one of the world’s largest development agencies. Its goal is to help developing countries to eliminate poverty, to preserve and regenerate the environment and to empower people and institutions. In the mid-1990s, when this book begins, the focus of the organization was on the fight against poverty and on community participation. In both of these areas, the emphasis was on strengthening national capacity, itself part of an overall approach of ‘sustainable development’.

IDO is financed by voluntary annual contributions. Its principal donors, depending on the year, are the USA, Japan, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Norway, Sweden, France, the United Kingdom, Canada, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, Austria, Australia, Finland and Spain. An internationally agreed-upon procedure determines the level of contribution by beneficiary countries to normal operations, taking into consideration each country’s population and per capita gross national product (GNP). Other criteria apply to countries with significant geographical handicaps or major economic difficulties.

IDO’s defining activities – the transfer of knowledge and the funding of development – have existed since well before the organization was created. In the colonial era, this approach to stimulating markets within colonies was a means of reinforcing the metropolitan economy. However, the real processes of transferring knowledge and financing development aid began at the end of the Second World War. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, better known as the World Bank) were founded at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, and were followed by the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) in 1945. Unlike bilateral aid, which is the transfer of funds from one government to another, multilateral aid comprises many donors acting as one, with no single donor directly controlling the aid programme.

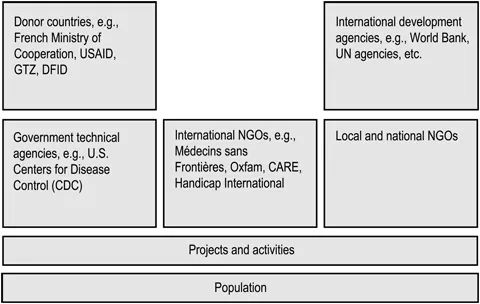

At the same time, numerous bilateral agencies were created by the wealthiest nations. These include France’s Ministry of Cooperation, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, created in 1961), the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (Deutsche Gesellschaft für technische Zusammenarbeit, or GTZ) and its British equivalent (the Department for International Development, DFID). International nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) active in development aid were also set up. Alongside the latter emerged local or national NGOs operating only in their country of origin. For example, an NGO created by a Bangladeshi citizen to help the women of Bangladesh create small businesses through micro-credit is categorized as national or local, so long as its activities do not go beyond the boundaries of Bangladesh (Ryfman 2004).

Various organizational actors in the development world created projects or programmes,2 and set about defining the methods and beneficiaries,3 as we shall see (Figure 1.1).

The field

Through a network of more than one hundred international offices, the IDO works in almost two hundred countries and territories in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Arab States, Eastern Europe and the ex-USSR. As the decentralized operational arm of IDO, this network of local offices provides various services, from supporting the creation of development programmes with policy advice to practical development work at country level. As we will see, the local offices constitute an information exchange network on a global scale, and provide ongoing training in development both to government employees and to the staff of IDO and their local partners. More than 80 per cent of IDO’s employees work in these country offices, and a similar proportion of staff in these offices are nationals of the host countries, recruited on site.

IDO staff members are thus divided between headquarters in New York and the local offices in developing countries. Reporting relationships between headquarters and local offices vary, but normally there is a certain amount of decentralization. Responsibility for field-based projects falls to the local office, while such tasks as coordination of activities, monitoring and evaluation, fundraising, reporting to donors and media relations are handled by headquarters. The New York headquarters is made up of several departments, including regional offices that cover the agency’s development programmes in each major region of the world. There are regional offices for Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Arab states, and finally an office created in the early 1990s for the countries of the ex-USSR and Eastern Europe.

All IDO local offices are run by National Representatives. In the interests of efficiency and decentralization, they are authorized to approve substantial budget projects on their own. Approval from New York is only necessary when project budgets exceed a particular threshold, or concern more than one country. The latter are called regional projects, and are often managed by headquarters, that is by the regional offices or the technical specialized offices. At the top of the hierarchical pyramid, National Representatives and New York offices are supervised by the Executive Head, who answers to a Programme Board.

In each IDO regional office, the programme managers direct the organization’s activities, following standardized codes of management. One manager may be given responsibility for creating and implementing activities focused on women, another for micro-credit programmes, a third for the organization of elections. Managers are based in New York, undertaking numerous missions to those countries affected by the activities for which they are responsible. Nevertheless, the IDO regional office in charge of ex-USSR and Eastern European countries in 1994 is not comparable in any degree with the other regional offices of the organization. It still has few personnel and budgets are small because the countries of the former Soviet Union have only very recently come to be considered developing countries, having thus lost their rank – and their privileges – as contributors to the organization’s budget. Among African, Latin American and Asian countries that have been classed as ‘developing’ for a long period of time, many grumble about the fact that IDO largesse must now be shared with these newcomers.

The regional office for Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union has little specific knowledge of the region because until very recently it was one of the great world powers, and therefore unlikely to receive development aid. The majority of staff, like my colleagues Beth, Anna, Mike or John (whom you will meet in the following chapters), are development professionals with experience working in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and know little or nothing about the ex-USSR.4 As will be seen, they gradually come to understand that the analyses, concepts and methods used in the ‘Third World’ for decades are ill adapted to the ‘Second World’ of the former Soviet republics.

A very small minority of the members of the New York team come from the ex-USSR. There are a few old apparatchiki who were employed by their governments during the Soviet era. Shaped by Soviet work practices, in 1994 they have little understanding of the agency’s internal functioning or more generally of the development field. There are also some under-30s, who did not work for their governments during the Soviet era, but who are often from the intellectual and political elite of their countries. This has given them the opportunity to acquire a perfect command of foreign languages and the ability to integrate rapidly into the United States-based international agencies. Although they are personally well acquainted with the region, they have no training in development issues and little previous professional experience to call on. For them, it is a time to invent, pioneer, innovate and even improvise. One needs to know how to take the initiative, persuade, define an action programme and find the funding.

Paradigm change: the development of ‘development’

The story begins at a moment when IDO already has thirty years of international experience. To understand how the various actors will create new methods for the promotion of good governance through activities such as HIV prevention that are, at first glance, unrelated, we need a brief genealogy of the ideas constituting the theoretical ‘building blocks’ current in New York at the beginning of our story.

In the mid-1960s, when IDO was created, the dominant hypothesis of the development paradigm was that economic growth – measured by economic indices such as GNP or per capita income – would result in a general rise in the standard of living thanks to the ‘trickle-down effect’, which would tend to reduce poverty (Copans 2006). This dominant theme among development professionals held that there was an inverse relationship between redistribution policies and growth. This was based on a simple principle: redistributing the income of the rich to the less rich would cause a reduction in the level of savings and thus reduc...