- 108 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tectonic Processes

About this book

This book, first published in 1981, provides an excellent introductory analysis to plate tectonic theory. It covers plate tectonics, continental drift, mountain building, ocean trenches, earthquakes and volcanoes.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Major features of the surface of the Earth

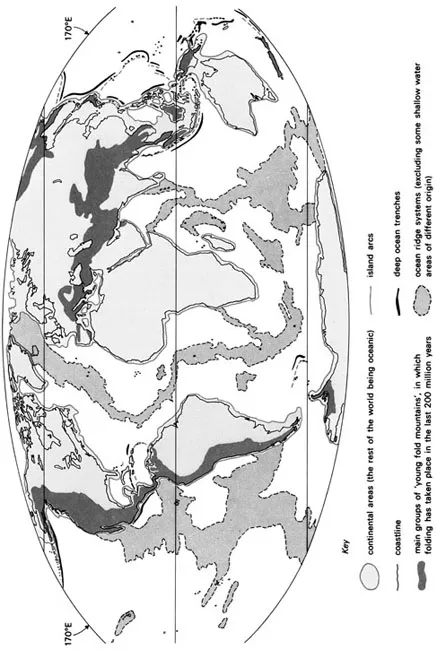

A casual glance at a world map in almost any atlas will be sufficient to make it clear that the geographer regards sea level as a rather fundamental marker point. Those areas of the Earth’s surface below sea level are virtually all covered by water and are generally coloured blue on a map, whereas ‘dry land’ appears in various shades of green and brown when the relief is to be shown. Even when the surface relief below sea level is shown, the shading is still in tones of blue, and it is not really possible to confuse areas of land and sea. If you asked a geologist to draw a world map, however, the result might well look a little more like Figure 1.1. Although this map may initially appear familiar, the overall colour effect is designed to divide the surface into continental and oceanic areas. The continental areas defined in this manner are slightly larger than the land areas of the geographer’s map, because they include the shallow-water continental shelves, which lie marginal to the land masses in some places.

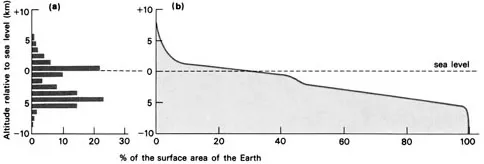

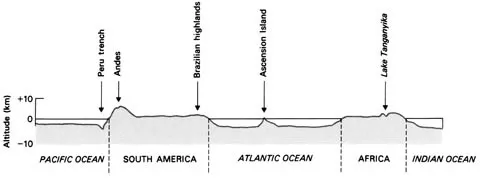

The geologist makes this fundamental distinction between continental and oceanic because, as we shall see later, the age and type of rocks underlying the two areas are somewhat different. The distinction also has geographical significance, however, and this can be seen most clearly by examining the relief of the Earth’s surface. Figure 1.2a is a histogram showing the total surface area of the Earth lying at different levels above and below sea level. As may be expected, only a small part of the Earth’s surface lies at the two extremes of altitude. On the one hand, mountain chains rise above sea level to heights of almost + 10 km, whereas below sea level the deep ocean trenches descend to below –10 km. Together, however, these amount to no more than about 10 per cent of the total surface area, leaving most of the surface lying between +2 km and –6 km. As Figure 1.2a makes clear, however, this huge area falls into two distinct levels: a higher one lying between + 2 km and – 1 km, and a lower level between – 3 km and – 6 km. This pattern is perhaps seen even more clearly if Figure 1.2a is redrawn as a cumulative frequency curve of altitude (Fig. 1.2b), which is commonly known as a hypsographic curve. The higher level obviously represents most of the land areas of the world plus the continental shelves, and the lower level represents the floor of the oceans. This altitude grouping provides a purely physical reason for distinguishing continental and oceanic areas. The small surface area between these two levels, shown by the steep central portion of Figure 1.2b, comprises the relatively steep slope connecting the edge of the continental shelves with the ocean floor and also the shallower areas of the oceans known as the ocean rises. It must be emphasised that Figure 1.2b in no way represents the geographical distribution of altitude. To make this point clearer, Figure 1.3 is a very generalised cross-section from the Pacific Ocean to Africa, on which the various altitude categories are shown in something like their true geographical setting.

The major features of the Earth’s surface are not only grouped by altitude; they are also grouped in space. Reference to Figure 1.1 should remind the reader that the continental areas are themselves rather obviously grouped: first, within the northern hemisphere; and also into the two blocks comprising the ‘Old World’ of Europe, Asia and Africa and the ‘New World’ of the Americas. As we have already seen, the surface of the continents lies largely below 2000 m, and much of this is either flat or has only low relief. This includes landscapes such as the rolling prairies of North America or the steppes of Asia, the high tablelands of Africa, the flat coastal plains of the Gulf of Mexico and the offshore continental-shelf areas of North-West Europe or South-East Asia. In many places hills and mountains stand above the surrounding lowlands, but even areas such as the Appalachians of North America or the Urals of central Russia are really no more than the eroded relics of former mountains when compared with the major mountain chains of the Earth. The mountain chains shown in Figure 1.1 are commonly referred to as young fold mountains, since they have been formed in the recent geological past, even if they include much older elements. These mountain belts include virtually all of the surface area above 2 km, and it is noticeable that they do not occur in random groups over the Earth but form long continuous chains. The two most important are: (a) the Andes–Rocky Mountain system, forming a line down the western seaboard of the Americas; and (b) the Alpine–Himalayan system, which forms a more or less continuous west–east chain between Europe and Asia to the north and Africa and India to the south. Although mountains form the most prominent linear feature on the continental surfaces, some continents are cut by linear depressions in the form of very long, deep and steep-sided valleys. Since the sides of these valleys are formed by the faulting, or ‘rifting’, of surface rocks, they are known as rift valleys. By far the most famous rift-valley system is that found in East Africa, which stretches from the Ethiopian Highlands in the north to Lake Nyasa in the south.

Figure 1.1 A world map showing those areas defined as continental and oceanic, together with some of the major linear structures of the Earth’s surface.

Figure 1.2 World relief: (a) A histogram showing the proportion of the world’s surface at various altitudes relative to sea level, (b) A cumulative frequency curve of world altitude, known as the hypsographic curve.

Where mountain chains run parallel to the coastline, as in the case of the Andes, offshore the seabed slopes steeply to the ocean floor at about – 3 km, and there is no real continental shelf. In this case the edge of the continental unit as a whole is close to the coastline (Fig. 1.1). Where a coastal plain meets the sea, however, it is often continued off-shore as a wide continental shelf before the continental slope, and therefore the edge of the continent proper, is met. The ‘edge’ of Europe, for example, is found some 400 km west of Ireland. Geologically speaking, as we have already intimated, continental shelf and coastal plain are more or less identical. They are part of the single structural unit that we are calling a continent, across the edge of which sea level migrates backwards and forwards over time as the volume of water in the oceans changes with the growth and decay of ice sheets. Although the shoreline seems to be so permanent a marker in human terms, over geological time its position is constantly changing.

Figure 1.3 A generalised section from Africa through South America to the Pacific, showing the geographical relationships of major surface features.

The oceanic areas themselves show just as much relief as the continents. In places the ocean floor between – 3 km and – 6 km is a true plain, but frequently the bottom has considerable relief. The abyssal plains (i.e. the area between – 3 km and – 6 km) are frequently interrupted by rises and depressions beyond this altitude range. Some rises are irregular groupings that form sea mounts, or islands if they reach sea level. More significant, however, are extensive linear systems on a scale analogous to that of the continental mountain chains. The first of these is the so-called ocean ridge (Fig. 1.1). These ridge systems are virtually submarine mountain chains, several hundred kilometres wide, which rise to a ridge usually less than – 2 km below sea level and frequently form islands. The most famous of these systems runs down the centre of the Atlantic, its course paralleling the adjacent coastlines perfectly, breaking the surface of the ocean at Iceland, the Azores, Ascension Island and other points. Similar features can be found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, but in these cases the ridge is nothing like central to the ocean basin. The other linear feature of the oceanic areas is the ocean trench, which has already been identified in the discussion on surface altitude. Reference to Figure 1.1 will show that the trenches are long, relatively narrow features descending to below – 10 km. They are grouped in linear fashion. The trench lying off the western coast of the Americas clearly runs parallel to the Andes–Rocky Mountains chain, and most other trenches in the world seem to lie parallel to groups of volcanic islands, which so often take on an arcuate plan that they have become known as island arcs. The clearest trench–island arc systems are found in the western Pacific in groups such as the Aleutian Islands, the Kuril Islands and the Marianas Islands.

1.2 The purpose and organisation of this book

This brief summary of the major features of the Earth’s surface should serve to indicate two things to the reader: first, that the surface of the Earth is very diverse, and second, that there is a pattern in the way in which the features are distributed around the world. It is the purpose of this book to describe these features in more detail and to offer a reasonable explanation for their origin and distribution. For some reason of historical accident, geographers seem quite happy to discuss the processes by which landscapes develop under the operation of agents of erosion (the province of geomorphology) but feel that an understanding of tectonic processes (i.e. those having their origin beneath the Earth’s surface) remains the exclusive right of the geologist. This is a viewpoint with which I have little sympathy. If to understand the Earth’s surface means using the geologist’s knowledge, then so be it.

In recent years, geologists have developed the theory of plate tectonics which is an attempt to explain many of the Earth’s major surface features through an understanding of the processes which operate deep beneath the surface. In this book we shall explore tectonic theory, by presenting the evidence upon which the theory has been developed. We shall start by looking at the evidence for continental drift which proved to be of crucial importance in the development of the more general theory. This is followed by a discussion of the evidence which has improved our understanding of the nature of the Earth’s interior and, thereby, has suggested a possible mechanism to explain the movement of the continents. We shall then return to the substance of the book by describing and attempting to explain the surface features found in different tectonic environments around the world.

During this journey of exploration we shall inevitably have to employ some geological terminology. As far as possible, technical words will be explained as we go along, but it is necessary to assume that you, the reader, have at least a passing acquaintance with the words used to describe rocks, minerals and geological time. If you have not met words such as ‘igneous’ or ‘sedimentary’, ‘granite’ or ‘sandstone’ before, it might be as well to glance at the Appendices provided at the end of the book now. If, however, you have at least the barest knowledge of basic geology then read on.

Chapter 2

Continental Drift

2.1 Introduction

At first, the notion that the continents are not fixed upon the surface of the Earth but wander across the globe seems preposterous. Nonetheless, the idea has periodically been proposed over the course of several centuries by scientists who have felt that the geological evidence can be interpreted in no other way. In 1912 Alfred Wegener, a German scientist, first collected together evidence from a number of different sources and thus earned himself the title of the originator of modern drift theory. Even so, Wegener’s ideas were met with scepticism or outright disbelief, and it was some time before the continuing accumulation of data became increasingly difficult to ignore. In this chapter we shall examine the nature of that evidence and begin to draw some conclusions about the movement of the continents. We shall, for the moment, ignore some of the recent seafloor evidence and keep strictly to what may be observed on the continents themselves.

2.2 The evidence for continental drift

2.2.1 Shape of the continents

It was in 1620 that Francis Bacon first observed that the eastern and western margins of the Atlantic Ocean seem to fit together in a way that can scarcely be accidental. Since that date many other writers have made the same observation, but it is by no means easy to make a convincing map to show that the Americas fit exactly against the coastline of Europe and Africa. In the case of Figure 1.1, for example, any attempt to place the shorelines together would result in numerous gaps or overlaps. There are two main reasons for this difficulty:

(a)Any map is an attempt to represent a curved surface on a flat page, and ultimately something has to be distorted to achieve that end. In some map projections the distances are not on a fixed scale, and in others it is the shape that suffers; but in either case a compromise is reached, which does not help with the problem of continental shape-fitting. Needless to say, the same difficulties attend all the maps in this book, even where care has been taken to minimise the problem.

(b)The coastlines of the continents may have suffered considerable alteration since splitting took place, as a result of erosion, deposition, volcanic activity or mountain-building. In the case of the Atlantic, for example, areas of river delta (e.g. the mouth of the Niger) have been built up by deposition in the recent geological past.

Within the last few years, various attempts have been made to improve the techniques of continental jigsaw-puzzle work. In some cases globes with movable surface features have been built; in others computers have been employed to fit continents in such a way as to leave a minimum of either gap or overlap. These ‘optimisation’ methods have been used most successfully by Sir Edward Bullard, who found, significantly, that the best Atlantic fit can be achieved not by using the coastline but by using the 2000 m below sea level contour (Fig. 2.1, but see also Fig. 4.1 for present-day Atlantic contours). The important point about this...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Tables

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Continental Drift

- Chapter 3 The Internal Structure and Mechanisms of the Earth

- Chapter 4 Constructive Plate Margins

- Chapter 5 The Surface of the Moving Plates

- Chapter 6 Destructive Plate Margins

- Chapter 7 Volcanoes and Earthquakes

- Appendix A Rocks and Minerals

- Appendix B The Geological Time Scale

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tectonic Processes by Darrell Weyman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.