- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, originally published in 1982, begins with an examination of space, and its role in the process of public provision and collective consumption. Variations in provision are linked to the Weberian notion of social status and political struggles over consumption and externality issues. Health care and education are considered in spatial contexts, and the whole basis of the electoral system is also discussed together with geographic underpinnings. In each case emphasis is placed on the jurisdictional organization of space by public bodies. The author examines the various examples of spatial cleavages, in which political events are redirected by issues such as nuclear power, airport location, road construction and urban renewal.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Location by Andrew Kirby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Space

1 A perspective on space

By virtue of the stress given by geographers to the spatial distribution of phenomena in vacuo, largely abstracted from their wider social contexts, they have unwittingly moved into an exploratory cul-de-sac productive of little more than often erroneous, spatially grounded, causal inferences, which simultaneously divert attention away from underlying social causes. (Chris Hamnett: Social Problems and the City (D. Herbert and D. Smith, eds))

Hamnett’s views represent one side of a central debate within contemporary geography which revolves about no less than the efficacy of studying anything from a spatial perspective. In the past geography has faced a good deal of academic indifference – and hostility – and the move towards the creation of a professional discipline has been a painful process, as Johnston shows (1979a, pp. 86–99). However, the present debate is all the more important (and some might say dangerous) because it is being conducted internally. A sizeable number of geographers have become disillusioned with the subject, and they feel, to paraphrase Hamnett’s argument, that a distinctly geographical approach can tell them less and less about anything of importance. To understand this standpoint more fully, we may usefully consider the ways in which space can be considered.

Space as an idea

The philosophical bases of space have been developed through several centuries:

in Kant’s time there were, briefly speaking, two opposed conceptions of the nature of space. There was the viewpoint of the Newtonians in which space was treated as a real entity, with an existence independent of both mind and matter. Space was a huge container in which atoms and planets swam like fish in a tank. The view of Leibniz, however, was that Newtonian space was logically paradoxical. Empty space, clearly a nothingness, was, by the container conception, also a somethingness. This contradiction led Leibniz to believe that space was an idea rather than a thing: that ‘space’ sprang from the mind when thought conceived a relationship between perceived objects, and had no more real and independent existence than the distance between two persons described as near or distant relations. In this case, space was entirely relative: and if the objects were removed, space disappeared. (Richards, 1974, p. 3)1

Despite their antiquity, the views of space held within geography have tended to follow these ‘relativist versus absolute’ stances (see Harvey, 1969, pp. 206–9). Sack, for example, identifies two particular schools of thought, one of which he terms the ‘spatial separatists’, the other the ‘chorologists’ (1980, p. 330). The former, as the name suggests, holds ‘that the spatial questions are about a separate subject matter – space; and that this subject matter required a separate kind of law or explanation – spatial laws and explanations’ (1980, p. 330). Chorology is to be seen as a counterpart to chronology: ‘the production of specific places, areas or regions, parallels the production of specific times such as an era or epoch in history’ (1980, p. 331).

Chorology, naturally enough, examines particular places (absolute space(s)), and can draw upon any method or body of knowledge to assist in that study. The relativist view of space is, however, a very different animal, simply because it does view space as an object of study in its own right: thus, as Sack observes, there must be ‘spatial laws’ developed in order to understand its operation.

It was on this basis that post-war geography staked its claim to academic individuality, with what Sack terms ‘spatial separatism’. Johnston in fact typifies much of the geography undertaken in the 1960s as being ‘a lower-level science of spatial relations, applying in empirical contexts the laws of higher-level, generally more abstract sciences’ (1979a, p. 98). Unsurprisingly, this concentration (some have described it as a fetishism) upon space as a ‘thing-in-itself has attracted detailed criticism. Sack himself has opposed separatism on philosophical grounds: simply, he argues that a unique geography must rest upon some innate properties of space, and these do not exist.

A more strident, and indeed wide-ranging attack, has come from an entirely different quarter, namely those who concentrate upon social and political issues. Some of the initial statements in this vein have in fact come from outside the subject, but the general thread of argument has been picked up and amplified by geographers themselves. In essence, the critique rests upon a rejection of the assumption that space can exist as an independent artefact, and that human spatial relations operate in the same way as atomic or planetary bodies. Soja observes:

while such adjectives as ‘social’, ‘political’, ‘economic’ and even ‘historical’ generally suggest, unless otherwise specified, a link to human action and motivation, the term ‘spatial’ typically evokes the image of something physical and external to the social context and to social action, a part of the ‘environment’, a context for society – its container – rather than a structure created by society. (1980, p. 210)

The argument here revolves around the assumption that space can be examined as a virtual abstraction. Such a notion is dismissed by two urban sociologists, Manuel Castells and Henri Lefèbvre. The latter writes:

If space has an air of neutrality and indifference with regard to its contents and thus seems to be ‘purely’ formal, the epitome of rational abstraction, it is precisely because it has already been the focus of past processes whose traces are not always evident in the landscape. Space has been shaped and moulded from historical and natural elements, but this has been a political process. Space is political and ideological. It is a product literally filled with ideologies.2 (1978, p. 341)

The same point is expressed with even greater succinctness by Castells: ‘one runs the very great risk of imagining space as a white page on which the actions of groups and institutions are inscribed, without encountering any other obstacle than the trace of past generations’ (1977, quoted by Soja, 1980, p. 212).

From these observations two inferences can immediately be made. The first is that space can only be understood as part of the operation of society; and the second is that space is used by society as an absolute thing: in other words it is of interest not in a relative sense (the distance between objects), but in the Newtonian context of a number of aquaria, within which we are located. Each portion of space has some particular importance (or meaning), and is used for a specific purpose: hence Lefèbvre’s contention that space is a political reality. In turn then, one further inference can be made: if space is a social and political phenomenon, then there may be little point in studying it in the manner that we know as geographical; it might only be understood by those who concentrate solely upon social structures.

Spatial schema, spatial structure and spatial patterns

Although the argument proposed by Castells and Lefèbvre does undermine the idea of spatial separatism, it need not, however, be taken to imply that spatial considerations are always valueless. Indeed, a good deal of the research undertaken within the broad realm of political economy has begun to explicitly examine the role of space in the functioning of the capitalist economy.

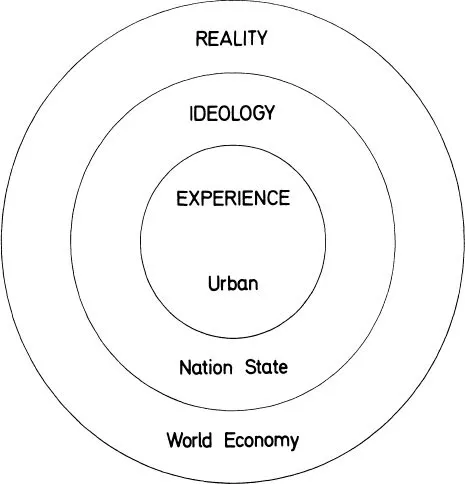

A particularly good example (albeit research within geography) is recent work done by Taylor, who provides a particularly stimulating analysis of how political geography can be approached using a political-economic perspective derived from Wallerstein (1980). Taylor’s argument is essentially that, although the economic system is global in character, we must at times change the spatial scale when attempting to understand the operation of that world economy. His argument is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

This simple diagram suggests that although economic activity is global in character (the ‘reality’), there exist in addition two subsidiary layers of understanding. The first of these is the nation state, which functions as an ideological3 entity, a means of harnessing loyalties: ‘nationalism is a mixture of idealist populism with hardheaded economic protectionism’ (Taylor, 1980, p. 25). In contrast to the ‘scale of ideology’ is the urban, which is described as the ‘scale of experience’, ‘the scale at which we live our daily lives’ (Taylor, 1980, p. 25). It is at this level that, for example, the state provides consumption goods (housing and so on), and at this scale that the crises within capitalism are manifested; the redundancies and the closures. All three interact as follows:

In political discussion in the Wallsend Constituency in North East England I have observed that a major topic of concern has been the health of shipbuilding. This is only natural since the Swan Hunter yards are the major employer in the area. If the yards close, the resulting unemployment will affect the whole town, making Wallsend the ‘Jarrow of the Eighties’. This is the scale of experience. It is at the scale of ideology that policy emerges however. The response to local pressures was for the Labour Government to nationalise British shipbuilding including Swan Hunter. This is ideological since it reflects only a partial view of the situation. It may protect jobs and ease the flow of state subsidies into the area, but it does not tackle the basic problem affecting shipbuilding. Both demand and supply in the Industry are global. The current problems in the Industry can be directly traced to the fall in demand following the 1973/74 oil price rise and the emergence of competitive suppliers from such countries as South Korea. Clearly a policy of nationalisation is a long way away from solving the problems of Wallsend’s shipyards. (Taylor, 1980, p. 20)

Taylor’s reading of Wallerstein provides us then with a rationale for examining phenomena at (at least) three spatial scales; not because it is an easy way to taxonomise or split up events, but because different things happen at different scales, and because it is difficult to examine something such as ideology at either the global or the local level. We can, however, take this a step further, in order to examine exactly why some activities are scale-specific, and in turn to test the effects of organizing any activity in a spatial domain. David Harvey, for example, has examined Marx’s view of economic development, and he concludes that ‘Marx recognised that capital accumulation took place in a geographical context and that it in turn created specific kinds of geographical structures’ (1978, p. 263). Indeed, Harvey is of the opinion that Marx’s outlines can be used to link up the process of capital formation with the emergence of imperialism, i.e. the diffusion of the capitalist system from one country to another: ‘the theory of accumulation relates to an understanding of spatial structure … and the particular form of locational analysis which Marx creates provides the missing link between the theory of accumulation and the theory of imperialism’ (1978, p. 263)

Figure 1.1 A rationale for the use of different spatial scales (after Taylor, 1980)

Although many geographical studies employ different scales of spatial resolution (international; national-regional; inter-urban; intra-urban), there is rarely any rationale given for these taxonomies. The emphasis upon nations and regions as obvious units of analysis is particularly worrying, as they are entirely artificial. Taylor’s development of Wallerstein’s ideas is one of the few attempts to critically account for the use of the particular scales ‘national’ and ‘urban’; it is to be noted that the regional scale – described by Sayer as a ‘chaotic conception’ – is not employed.

Harvey goes on to argue that distant lands serve to provide the core (of, for example, a nation) with three things: a surplus of labour, a supply of surp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I Space

- Part II Inequalities

- Part III Conflicts

- Part IV Change

- Name index

- Subject index