![]()

Cooperative learning in elementary schools†

Robert E. Slavina,b

Cooperative learning refers to instructional methods in which students work in small groups to help each other learn. Although cooperative learning methods are used for different age groups, they are particularly popular in elementary (primary) schools. This article discusses methods and theoretical perspectives on cooperative learning for the elementary grades. The article acknowledges the contributions from each of the major theoretical perspectives and places them in a model that depicts the likely role each plays in cooperative learning outcomes. This work explores conditions under which each perspective may operate, and suggests further research needed to advance cooperative learning scholarship.

Cooperative learning refers to teaching methods in which students work together in small groups to help each other learn academic content. In one form or another, cooperative learning has been used and studied in every major subject, with students from pre-school to college, and in all types of schools. However, they have been particularly popular in the elementary grades, where greater flexibility in daily schedules makes it easier to do cooperative work.

There have been many studies of cooperative learning focusing on a wide variety of outcomes, including academic achievement in many subjects, second language learning, attendance, behaviour, intergroup relations, social cohesion, acceptance of classmates with disabilities, attitudes towards subjects, and more (see Johnson and Johnson 1998; Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec 2008; Rohrbeck et al. 2003; Slavin 1995, 2010, 2013). This article focuses on research on achievement outcomes of cooperative learning in elementary schools, and on the evidence supporting various theories to account for effects of cooperative learning on achievement.

Theoretical perspectives on cooperative learning

While there is a fair consensus among researchers about the positive effects of cooperative learning on student achievement (Rohrbeck et al. 2003; Roseth, Johnson, and Johnson 2008; Sharan 2002; Slavin 2010, 2013; Webb 2008), there remains a controversy about why and how cooperative learning methods affect achievement and, most importantly, under what conditions cooperative learning has these effects. Different groups of researchers investigating cooperative learning effects on achievement begin with different assumptions and conclude by explaining the achievement effects of cooperative learning in terms that are substantially unrelated or contradictory. In earlier work, Slavin (1995, 2010, 2013) identified motivationalist, social cohesion, cognitive developmental, and cognitive-elaboration as the four major theoretical perspectives on the achievement effects of cooperative learning.

The motivationalist perspective presumes that task motivation is the single most impactful part of the learning process, asserting that the other processes such as planning and helping are driven by individuals’ motivated self-interest. Motivationalist-oriented scholars focus more on the reward or goal structure under which students operate. By contrast, the social cohesion perspective (also called social interdependence theory) suggests that the effects of cooperative learning are largely dependent on the cohesiveness of the group. This perspective holds that students help each other learn because they care about the group and its members and come to derive self-identity benefits from group membership (Johnson and Johnson 1989, 1999, 2008). Within this perspective, there is a special case, task specialisation methods, in which students take responsibility for unique portions of a team assignment (Aronson et al. 1978; Sharan and Sharan 1992). The two cognitive perspectives focus on the interactions among groups of students, holding that in themselves, these interactions lead to better learning and thus better achievement. Within the general cognitive heading, developmentalists attribute these effects to processes outlined by scholars such as Piaget and Vygotsky. Work from the cognitive elaboration perspective asserts that learners must engage in some manner of cognitive restructuring (elaboration) of new materials in order to learn them. Cooperative learning is said to facilitate that process.

This article offers a theoretical model of cooperative learning processes as applied in elementary schools which intends to acknowledge the contributions of work from each of the major theoretical perspectives. It places them in a model that depicts the likely role each plays in cooperative learning outcomes. This work further explores conditions under which each may operate, and suggests research and development needed to advance cooperative learning scholarship so that educational practice may truly benefit from the lessons of 30 years of research.

The alternative perspectives on cooperative learning may be seen as complementary, not contradictory. For example, motivational theorists would not argue that the cognitive theories are unnecessary. Instead, they assert that motivation drives cognitive process, which in turn produces learning. They would argue that it is unlikely that over the long haul students would engage in the kind of elaborated explanations found by Webb (2008) to be essential to profiting from cooperative activity, without a goal structure designed to enhance motivation. Similarly, social cohesion theorists might hold that the utility of extrinsic incentives must lie in their contribution to group cohesiveness, caring, and pro-social norms among group members, which could in turn affect cognitive processes.

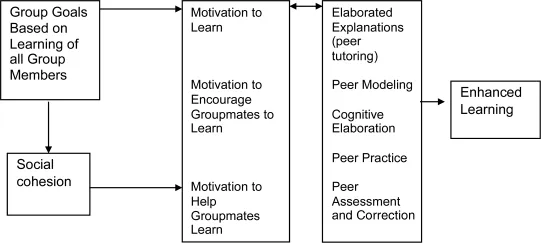

A simple path model of cooperative learning processes, adapted from Slavin (1995), is diagrammed in Figure 1. It depicts the functional relationships among the major theoretical approaches to cooperative learning.

The diagram of the interdependent relationships among each of the components in Figure 1 begins with a focus on group goals or incentives based on the individual learning of all group members. That is, the model assumes that motivation to learn and to encourage and help others to learn activates cooperative behaviours that will result in learning. This would include both task motivation and motivation to interact in the

Figure 1.A model of cooperative learning effects on learning.

group. In this model, motivation to succeed leads to learning directly, and also drives the behaviours and attitudes that lead to group cohesion, which in turn facilitates the types of group interactions; peer modelling, equilibration, and cognitive elaboration, that yield enhanced learning and academic achievement. The relationships are conceived to be reciprocal, such that as task motivation leads to the development of group cohesion, that development may reinforce and enhance task motivation. By the same token, the cognitive processes may become intrinsically rewarding and lead to increased task motivation and group cohesion.

Each aspect of the diagrammed model is well represented in the theoretical and empirical cooperative learning literature. All have well-established rationales and some supporting evidence. What follows is a review of the basic theoretical orientation of each perspective, a description of the cooperative learning mode each prescribes, and a discussion of the empirical evidence supporting each.

Four major theoretical perspectives on cooperative learning and achievement

Motivational perspectives

Motivational perspectives on cooperative learning presume that task motivation is the most important part of the process, believing that the other processes are driven by motivation. Therefore, these scholars focus primarily on the reward or goal structures under which students operate (see Slavin 1995). From a motivationalist perspective, cooperative incentive structures create a situation in which the only way group members can attain their own personal goals is if the group is successful. Therefore, to meet their personal goals, group members must both help their groupmates to do whatever enables the group to succeed, and, perhaps even more importantly, to encourage their groupmates to exert maximum efforts. In other words, rewarding groups based on group performance (or the sum of individual performances) creates an interpersonal reward structure in which group members will give or withhold social reinforcers (e.g. praise, encouragement) in response to groupmates’ task-related efforts (see Slavin 1983).

The motivationalist critique of traditional classroom organisation holds that the competitive grading and informal reward system of the classroom creates peer norms opposing academic efforts (see Coleman 1961). Since one student’s success decreases the chances that others will succeed, students are likely to express norms that high achievement is for ‘nerds’ or ’teachers’ pets’. However, by having students work together towards a common goal, they may be motivated to express norms favouring academic achievement, to reinforce one another for academic efforts.

Not surprisingly, motivational theorists build group rewards into their cooperative learning methods. In methods developed at Johns Hopkins University (Slavin 1994, 1995), students can earn certificates or other recognition if their average team scores on quizzes or other individual assignments exceed a pre-established criterion. Methods developed by David and Roger Johnson (1998; Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec 2008) and their colleagues at the University of Minnesota often give students grades based on group performance, which is defined in several ways. The theoretical rationale for these group rewards is that if students value the success of the group, they will encourage and help one another to achieve.

Empirical support for the motivational perspective

Considerable evidence from practical applications of cooperative learning in elementary schools supports the motivationalist position that group rewards are essential to the effectiveness of cooperative learning, with one critical qualification. Use of group goals or group rewards enhances the achievement outcomes of cooperative learning if and only if the group rewards are based on the individual learning of all group members (Slavin 1995, 2010, 2013). Most often, this means that team scores are computed based on average scores on quizzes which all teammates take individually, without teammate help. For example, in Student Teams-Achievement Divisions, or STAD (Slavin 1994), students work in mixed-ability teams to master material initially presented by the teacher. Following this, students take individual quizzes on the material, and the teams may earn certificates based on the degree to which team members have improved over their own past records. The only way the team can succeed is to ensure that all team members have learned, so the team members’ activities focus on explaining concepts to one another, helping one another practice, and encouraging one another to achieve. In contrast, if group rewards are given based on a single group product (e.g. the team completes one worksheet or solves one problem), there is little incentive for group members to explain concepts to one another, and one or two group members may do all the work (see Slavin 1995).

In assessing the empirical evidence supporting cooperative learning strategies, the greatest weight must be given to studies of longer duration. Well executed, these are bound to be more realistically generalisable to the day-to-day functioning of classroom practices. A review of 42 studies of cooperative learning in elementary schools that involved durations of at least four weeks compared achievement gains in cooperative learning and control groups. Of 32 elementary studies of cooperative learning methods that provided group rewards based on the sum of group members’ individual learning, 28 (88%) found positive effects on achievement, and none found negative effects (Slavin 1995). The median effect size for the studies from which effect sizes could be computed was +.26 (26% of a standard deviation separated cooperative learning and control treatments). In contrast, eight studies of methods that used group goals based on a single group product or provided no group rewards found few positive effects, with a median effect size of only +.07. Comparisons of alternative treatments within the same studies found similar patterns; group goals based on the sum of individual learning performances were necessary to the instructional effectiveness of the cooperative learning models (e.g. Chapman 2001; Fan- tuzzo, Polite, and Grayson 1990; Fantuzzo et al. 1989).

Social cohesion perspective

A theoretical perspective somewhat related to the motivational viewpoint holds that the effects of cooperative learning on achievement are strongly mediated by the cohesiveness of the group. The quality of the group’s interactions is thought to be largely determined by group cohesion. In essence, students will engage in the task and help one another learn because they identify with the group and want one another to succeed. This perspective is similar to the motivational perspective in that it emphasises primarily motivational rather than cognitive explanations for the instructional effectiveness of cooperative learning. However, motivational theorists hold that students help their groupmates learn primarily because it is in their own interests to do so. Social cohesion theorists, in contrast, emphasise the idea that students help their groupmates learn because they care about the group. A hallmark of the social cohesion perspective is an emphasis on teambuilding activities in preparation for cooperative learning, and processing or group self-evaluation during and after group activities. Social cohesion theorists have historically tended to downplay or reject the group incentives and individual accountability held by motivationalist researchers to be essential. They emphasise, instead, that the effects of cooperative learning on students and on student achievement depend substantially on the quality of the group’s interaction (Battisch, Solomon and Delucchi 1993). For example, Cohen (1986, 69–70) stated

if the task is challenging and interesting, and if students are sufficiently prepared for skills in group process, students will experience the process of groupwork itself as highly rewarding... never grade or evaluate students on their individual contributions to the group product.

Cohen’s (1994) work, as well as that of Shlomo Sharan and Yael Sharan (1992) and Elliot Aronson et al. (1978), may be described as social cohesiveness theories. Cohen, Aronson, and the Sharans all use forms of cooperative learning in which students take on individual roles within the group, which Slavin (1983) calls ’task specialisation’ methods. In Aronson’s Jigsaw method, students study...