![]()

Part I

Concepts and research design

![]()

1

Researching participation in environmental governance through the implementation of the European Water Framework Directive

Jens Newig, Elisa Kochskämper, Edward Challies, Nicolas W. Jager

“Public participation is not an end in itself but a tool to achieve the environmental objectives of the Water Framework Directive”.

(EU 2003: 6)

“The value of public participation will ultimately be judged by its ability to enhance implementation and show demonstrable benefits for environmental quality”.

(Beierle & Cayford 2002: 76)

The need to more systematically study participation in environmental governance

Public and stakeholder participation in public environmental decision-making is widely assumed to foster effective governance and secure environmental benefits. While historically, the motives and rationales for participation have centred around notions of emancipation and legitimacy, there has been a recent shift towards an expectation of increased effectiveness of governance (Newig 2012). Following this instrumental rationale, participation is advocated and used to open up decision-making, integrating local knowledge and the perspectives of a multitude of actors (Smith 2003; Edelenbos et al. 2011), and to promote acceptance and implementation of decisions (Bulkeley & Mol 2003). Participation is thus assumed to lead “to a higher degree of sustainable and innovative outcomes” (Heinelt 2002: 17). The introductory quotations (EU 2003: 6; Beierle & Cayford 2002: 76) are indicative of the many voices, from academia and politics, which argue that the success of participatory governance will ultimately be judged by its ability to improve environmental conditions.

And yet, the expectation that participation helps to solve environmental problems remains largely unsubstantiated, and widely disputed (Dietz & Stern 2008; Lange et al. 2013; Young et al. 2013). Even where strong relations between collaborative processes and environmental outcomes are empirically established, it remains unclear why and how this is the case (Scott 2015). Previous research has analysed single cases, or provided more aggregated comparisons of very different existing cases (Chess & Purcell 1999; Newig & Fritsch 2009; Beierle & Cayford 2002).

This volume seeks to move a step further in establishing causality between participation and environmental outcomes. It provides a systematic, comparative study of eight cases of participatory governance and their environmental outcomes. In studying sustainable water management planning under the European Water Framework Directive between 2005 and 2010, we are able to analyse multiple cases with varying degrees of participation in a similar context, in what is an ideal research setting for tracing causal mechanisms at work.

Participation is almost never a strict necessity. Even where it is legally mandated to some degree, there remains substantial leeway for decision-makers in terms of exactly how to design and execute a participatory process. Participation is therefore a deliberate choice made by public managers. In this respect, we conceive of participatory forms as strategic interventions that can help achieve certain goals (Scott & Thomas 2016).

Our focus lies on the instrumental value of collaboration and participation in environmental governance. We acknowledge that participatory and collaborative environmental decision-making may have a range of non-environmental outcomes that would be important to consider in gauging the overall impact of a decision-making process (Rogers & Weber 2010). In this book, however, we deliberately limit our focus to the implications of decision-making for the environment. We do not advance any particular ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ participation argument, but rather seek to examine in detail how different forms of participation benefit the environment and through which causal mechanisms this is the case – and where and how participation may even hinder good environmental outcomes.

The European Water Framework Directive as an ideal test-bed

Participatory water management planning under the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) provides a particularly apt setting to research the link between participation and environmental outcomes.

First, sustainable water governance itself is a policy field of major importance, which has incorporated collaborative approaches from early on (Sabatier et al. 2005; Pahl-Wostl 2009). The EC Water Framework Directive (WFD, Directive 2000/60/EC) was passed in 2000 as the centrepiece of the European water resource management regime to transform and harmonise the EU water policy sector (Boeuf & Fritsch 2016; Kaika 2003). Targeting “good water status” in all European waters, the Directive introduces a general integrated framework encompassing different types of water resources and their uses, as well as various political decision-making arenas and stakeholder interests, under one common legal regime (EU 2003). Particular emphasis in this respect is put on the detailed and ambitious procedural requirements by which this goal should be achieved. Embodying the paradigm of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) (Molle 2009; Jaspers & Gupta 2015), the Directive introduces key governance innovations to sustainably manage water on the level of river basin districts rather than territorial jurisdictions (Jager 2016; Jager et al. 2016; Moss 2012).

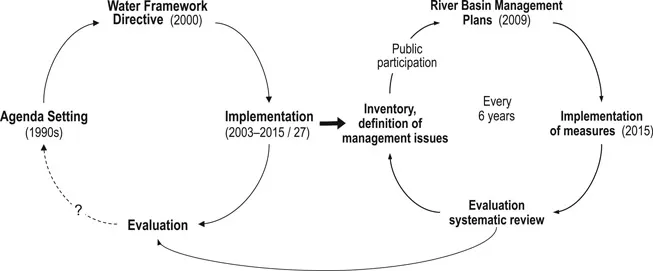

Second, the WFD explicitly mandates participation in the course of its implementation. In following a “mandated participatory planning approach” (Newig & Koontz 2014), the Directive requires that Member States develop formal planning documents every six years, which serve as the essential vehicles of implementation (see Figure 1.1). These planning documents must be developed in interaction with local citizens and stakeholders. To underscore the importance of participation in these planning processes, the EU has issued a guidance document solely devoted to public participation (EU 2003).

Figure 1.1 Nested policy cycle of the Water Framework Directive to illustrate theWFD’s mandated participatory planning approach

Note: Public participation informs River Basin Management Plans, which serve as the main vehicle for implementation. It is not clear yet how planning and implementation efforts will inform future policy formulation at the EU level.

Source: Newig and Koontz (2014)

According to Article 14 WFD, participation is required regarding information provision and the consultation of interested parties, while ‘active involvement’ – most notably in the development of planning documents – is merely encouraged. The Directive therefore leaves considerable room for interpretation as to who should be involved, at what stage, and how (Jager et al. 2016; Newig et al. 2014; Wright & Fritsch 2011). Clearly, the directive has introduced participation with an instrumental, effectiveness-oriented rationale. Public participation is seen as the central element of the WFD planning process (EU 2003: 55) and a key success factor for the Directive’s implementation (Preamble 14 WFD). Specifically, the guidance document on public participation in relation to the WFD clarifies that “Public participation is not an end in itself but a tool to achieve the environmental objectives of the Directive” (EU 2003: 6). With these explicit aims, the WFD lends itself well to an investigation of whether participation actually delivers as anticipated.

Third, WFD implementation processes follow the logic of a quasi-experimental setting within which to study and compare participatory processes and their outcomes. Participatory processes across the European Union take place in a similar context (water issues), with the same purpose (to contribute to sustainable water management planning), and at the same time (mid-2000s), thus facilitating the isolation of causal linkages between participatory processes and their environmental outcomes. We study eight participatory processes in three EU Member States (Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom), using a diverse pair case design (Gerring 2007) that maximises variation on the independent variable (participation), while still allowing for some generalisation across countries.

Fourth, despite the completion of the first full planning cycle in 2015, broader insights into the actual implementation and efficacy of the governance innovations introduced by the WFD remain fragmented. While studies on the implementation of the WFD proliferate (Boeuf & Fritsch (2016) counted 89 articles), most of these rely on a single case study design, and relatively few comparative analyses are available (see e.g. Hering et al. 2010; Jager et al. 2016; Liefferink et al. 2011). Furthermore, relatively few studies assess the governance innovations of the WFD in relation to their efficacy, both in relation to social and substantive outcomes (see e.g. Graversgaard et al. 2017; Hophmayer-Tokich & Krozer 2008; Kochskämper et al. 2016; Newig et al. 2016). While drawing on these earlier studies, this volume contributes substantially to the growing body of literature on governing WFD implementation through its systematic and comparative approach.

Every research design has its trade-offs. Studying WFD planning constitutes a mostly relatively technical process with a limited degree of ‘politicisation’. In contrast to cases of public protest or public mediation processes, the WFD only seldom makes headline news. Nonetheless, the WFD is one of the most important pieces of EU environmental policy, and given the central role assigned to participation in the course of its implementation, the findings of this study will not only be relevant to scholars and practitioners of participatory governance, but also to those engaging with water management planning in Europe and environmental governance more generally.

Structure of the book

We start our study by presenting in chapter 2 a conceptual framework of key mechanisms specifying potential (positive and negative) effects of participation on the environmental quality of governance outcomes, drawing on the available literature and recent syntheses (e.g. Drazkiewicz et al. 2015; Emerson & Nabatchi 2015; Fritsch & Newig 2012; Newig et al. 2013; Newig et al. 2017).

Chapter 3 introduces our empirical research design, including the case selection procedure and research methods. It provides an overarching account of the research process, including interview guideline design, semi-structured interviews, coding system and the development of comparable case descriptions.

Chapters 4, 5 and 6 are devoted to qualitative case study narratives of WFD planning in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom respectively. They each follow a common structure, first describing the legal transposition of the WFD in the respective country; the institutional setting, including the different administrative levels and competent authorities engaged in implementation; and the local-level sub-basin participatory planning processes, which are the focus of the case studies. While we focus on local processes, these are presented in the context of the multi-level structure of participatory WFD implementation. The cases are presented in detail, aiming for as complete an account as possible regarding input, throughput and output of processes. Local context and the main pressures on the water environment in the respective sub-basins are described, as are policymakers’ rationales for process design, participant selection, stake-holder characteristics, the planning process itself (in terms of dialogical setting, knowledge integration, communication and decision mode), as well as process outputs and outcomes. The WFD provides for subsequent planning cycles: Between transposition into law and 2009, Member States were required to develop the first management plans. From 2009 the WFD requires on-going implementation and updating of plans in six-year management cycles. Therefore we also compare 2009 and 2015 management plans to analyse implementation. Finally, we identify social outcomes such as collective learning and network building. We also report, albeit to a lesser extent, on the second participation round from 2009 to 2015 in order to provide a more complete picture on the iterative engagement of participation as a policy instrument. We conclude each chapter with a brief within-country comparison.

Chapter 7, building on the eight empiric...