![]()

1

Introduction

Patricia Edgar

Syed A. Rahim

As the world has advanced, the task of communication has become ever more complex and subtle—to contribute to the liberation of mankind from want, oppression and fear and to unite it in community and communion, solidarity and understanding. However, unless some basic structural changes are introduced, the potential benefits of technological and communication development will hardly be put at the disposal of the majority of mankind—International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems, UNESCO, 1979

Communication policy issues are now being debated intensely in various international fora, particularly in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). UNESCO’s intergovernmental general conferences and the UN General Assembly sessions have made several attempts over past years at formulating international norms and standards for communication in promoting peace and understanding. In 1948 the United Nations adopted a resolution upholding the concept of free flow of information and the fundamental human right to freedom of expression. But with the growth of many newly independent nations and an upsurge in nationalism, a growing concern about existing imbalances in the international flow of information has been expressed strongly. Uncertainty about the impact of new communication technology has further aggravated that concern.

The Third World nations have initiated a call for “a new world communication and information order” that would remedy the unsatisfactory situation in world communication. The umbrella concept of “a new order” has become a controversial matter for debates and decisions on international communication. The concept encompasses a wide variety of issues and problems: a free and balanced flow of information; equitable access to communication resources; prior consent of states for direct satellite broadcasting and remote sensing by communication satellites; protection of privacy in transborder data flows; transfer of communications technology; the cultural impact of communications development; communication planning for efficient and equitable resource allocation across nations; international cooperation for communication development in the developing countries; and institutional reform in the established order of communications systems dominated by a few developed countries.

In 1978 the UNESCO general conference in Paris adopted by acclamation a declaration on the fundamental principles governing the use of mass media for international peace and understanding. This declaration and a follow-up UN resolution endorsed the need for a more just and effective world communication order based on the free and better-balanced flow of information, and urged nations to cooperate in developing communication systems in less developed countries. In 1979 the World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC) sponsored by the ITU took far-reaching decisions relating to the allocation and use of radio spectrum and geostationary satellite orbits. Here again the main principle adopted was that of an equitable and effective allocation of limited natural communication resources for all countries of the world. With that, the ITU abandoned its older tradition of the “first come, first served” principle of resource allocation. The 1979 WARC could not settle all the issues concerning access to and equitable and effective allocation of resources, but decided to hold special conferences in the 1980s to formulate specific policies and plans for better utilization of the shortwave radio frequency for broadcasting, and the orbital space for communication satellites.

The participants in the international debates over communication policy have lacked access to well-organized information on communication problems in a world context. To help alleviate the situation, UNESCO constituted an international commission to study the totality of communication problems and make recommendations for practical action. Under the chairmanship of Sean MacBride from Ireland, the commission, with members from Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, France, India, Indonesia, Japan, Netherlands, Nigeria, Soviet Union, Tunisia, United States, Yugoslavia, and Zaire, completed its study in late 1979 (MacBride 1980). The commission made a strong case for communication policy and planning. In its view, the role and function of communication in modern society has become a matter of central importance, hence communication policymaking and planning should be incorporated into overall national policy and planning for development and progress, and a better mechanism should be developed for international coordination and cooperation. The commission identified a number of specific areas where the challenge for concerted action is very serious. Among these are the problems of imbalance in international communication flows, distortion of content in communication, undesirable effects of external communication on national cultures, barriers to the democratic flow of communication, rights and responsibilities of journalists, international cooperation for the development and better use of communication, and special problems of improving the communications infrastructure in developing countries.

The international debates about communication policy analysis and long-range planning raise difficult questions and problems for the developed industrial countries as well as the developing countries. While the nature of the problems in the developed and the developing countries is different, finding solutions requires collaboration and concerted efforts by all countries. An understanding of the differences, the similarities, and the common issues is essential for collaboration and effective solution of the problems. The problems stemming from the communications revolution in developed countries relate more to employment issues, life-style changes, philosophical issues relating to freedom of information and privacy, and concerns about the way communication resources are being developed and distributed. The Third World countries face the same problems as they attempt to develop and modernize their communication systems. They also face (or at least perceive) an additional problem of the threat to their national sovereignty and cultural integrity posed by the new technology combined with the commercial push from the transnational communication enterprises.

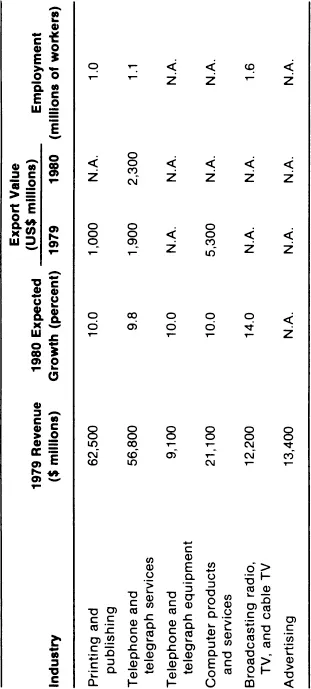

At one end of the development spectrum is the United States, a country that since the end of the Second World War has been a massive supplier of media products—books, news, film, television—to the rest of the world, yet its communication system is not dependent on foreign products. The United States’ dominant position in communication technology and in world communication markets is one example of its economic power. The communication sector of the United States, which ranks higher in terms of growth and profitability than many other sectors of industry, today is a very important sector indeed. A 1980 survey of U.S. industries shows that 100 out of 1,000 large public companies with annual sales of $3,000 million or more are communication-information enterprises. The enormous size and growth of the communication industry in the United States can be seen from Table 1-1.

Other communication industries in the United States are also very large and growing operations. The 1979 figures showing sales of products and services of some of these industries include: photographic equipment and supplies $13,300 million, consumer electronics $6,700 million, motion picture box office receipts $3,000 million, and advertising agency billings $23,300 million. The U.S. commitment to private ownership and to the profit motive is unique in its application to the formulation of communication policies compared with other developed countries. Other Western countries have evolved a range of models that incorporate both public and commercial control of the media within a context of free speech and democratic ideals. Often government intervention and public control of the media have been a direct result of the influence of the free flow of American information and technology around the world.

Table 1-1

Financial Growth of the U.S. Communication Industry

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1980.

Note: N.A. = not available.

In response to this enormous growth in the communication industries and the social and political problems that have emerged, there has been significant development in the academic field of communication. Academic research on the political economy of communication and on the information economy is striving to find new rationales, concepts, and methods for the policy analysis and planning of communication systems. The concept of the “information society” proposed in the works of American writers such as Machlup (1962), Bell (1973), Drucker (1968), and Porat (1976) is providing one foundation for a new paradigm for policy research and analysis. The approach is based on the notion that advanced industrial society is moving toward a new stage where the production, processing, and distribution of information will be the central societal activity. This is reflected in the trends of the economy, industrial growth, work organization, the leisure activities of people, and various social and economic transactions based on the exchange of information. A similar intellectual movement in Japan compares the evolution of industrial society to biological evolution. As the brain and nervous system in human biology are at the most advanced stage of evolution, so is the information industry in the industrial society. The rise of the information industry is a step forward on the path of evolution, its dominance indicating the coming of the information society (Ito 1979). (Ito reviewed the work of Japanese scholars and the Japanese concept of information society [Johoka].)

In a recent study of the U.S. economy, Marc Porat claims that the United States is now “an information economy.” He shows that the production, processing, and distribution of information account for about half of the gross national product and more than half of the wages in the U.S. economy. He argues that since communication capability is closely linked to the power and wealth of society it is essential that public policy deal effectively with the emerging problems of communication, and he places high priority on these issues. The technological revolution is creating great potential for expansion and change of the communication infrastructure, and therefore the focus of attention of communication policymaking should be at the level of the infrastructure. Porat believes that the crucial communication factors do not belong to the cultural superstructure of society, but rather are concerned with the basic technological and economic foundations of the information society (Porat 1976, 1978).

The technology-centered framework for communication policy analysis is proposed by scholars from the two countries most advanced in communication technology and industry: the United States and Japan. This shows that an integral relationship exists between the development of material conditions in a society, the intellectual pursuit of knowledge, and the practical concern for the application of knowledge. The research approach that examines the information economy is still emerging, and its application is limited to a few projects, including studies initiated by Lamberton in Australia and by an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) group working on information, computer, and communication policy.

Scholars who analyze communication problems from a cultural-theoretical framework are also reacting to the trend of expanding communication industries in advanced capitalist economies. In some recent academic works, a call for a major revision within cultural theory demonstrates the effects of that reaction. British academics—Raymond Williams, Nicholas Garnham, Stuart Hall, Graham Murdock, and Peter Golding—argue that in the increasingly complex structure of the advanced industrial society it is impossible to separate the process of production and distribution of communication from other economic processes (Curran, Gurevitch, and Woollacot 1979; Garnham 1979). Moreover, as the communication industry becomes dominant, its relationship to culture grows stronger and more complex. The theoretical formulations of earlier years—including the classical Marxian metaphor of the economic base and the cultural superstructure in which communication and culture belong to the superstructure; the associated view that the mass media operate as ideological apparatuses of the ruling class, providing ideological support for the economic base; the cultural-theoretical elaboration of the concept of relative autonomy of the superstructure from the economic base, with the mass media playing a distinctive and independent role in shaping that economic base—do not seem to provide adequate theoretical formulations and tools for a proper analysis of the objective conditions of communication in advanced industrial societies. Hence, a theoretical refinement of the conceptual categories and the place of communication in them has become necessary.

The case for elaboration of a political economy of mass communication presented by Garnham (1979) and Murdock and Golding (1977) stresses the importance of examining the economic structure of the growing communication industry and its relationship to the state. In their view the production and distribution of information or the “culture industry” is an essential element of the economic base in the Marxian sense, and the ideological and legal aspects of communication are in the category of a superstructure. It follows logically that an analysis of communication problems should begin with a study of the ownership, management, and economic structure of the communication industry, and then move into a critical cultural study of content, effects, and audiences. Only then can the problems be understood properly in their appropriate contexts. Such an approach, they argue, will be “intensely practical,” and will bring to light the real nature of the communication policy problems in advanced capitalist societies.

To understand the impact of the technological, economic, and political forces on the process of communication development in industrial countries, the necessary first step is to look at the totality of the communication system at the national level. The various components of national communication systems—the press and publications, cinema, broadcasting, telemetric and informatics, and telecommunications—need to be examined from both an economic and a cultural perspective. In every country the government plays a major role in influencing the communication sector through direct policy intervention, indirect regulatory control, or, as in the United States, a policy of relative nonintervention. Therefore the relationship between the government and the autonomous or private communication enterprises is an important aspect of the communication system to be examined for policy analysis.

Government initiative in studying the changing environment of communication and assessing its long-range implications for policymaking and planning is evident in a number of reports published recently. In Australia the national Telecommunications Commission conducted extensive studies on long-range policy and effective planning approaches. There were seven inquiries into aspects of communication occurring in Australia in 1981. A commission for the development of telecommunications systems constituted by the West German government has examined the problem of integrating the new communication technology and services into the existing communication establishments. In Britain, three different study commissions reviewed the press, broadcasting, and the telecommunications policy problems. The Canadian government initiated a serie...