![]()

Chapter one

Home-based reinforcement for changing children’s school behaviour

David J. Leach

As a result of over twenty years of research, applied behavioural psychologists working in educational settings have a wide range of demonstrably effective procedures to call on in order to reduce disruptive classroom behaviour, increase appropriate behaviour, and accelerate learning. The availability of a pool of effective procedures, however, does not infer that any one procedure may be selected at random and applied with equal success to any other in the resolution of a referred problem. This is particularly true in open settings such as schools and homes where psychologists often work as consultants, advising others (especially teachers and parents) on the implementation of intervention programmes for child behaviour change. When others are to carry out the behavioural intervention, they must understand the recommended procedure and then carry it out to its conclusion before it can begin to be successful. A mis-applied or non-applied intervention plan, however carefully designed, is simply no intervention at all and is unlikely to be of value. Indeed, a programme that has failed to be implemented as intended could lead to negative effects, such as a reduction in the perceived utility of consultant advice or generally less satisfactory collaborative problem-solving efforts in the future. Consultee acceptance, co-operation, and persistence then are of paramount importance when choosing between alternative interventions which involve others as mediators or deliverers of the programme; successful interventions are likely to be those which are matched not only to desired target behaviours but also to the direct change agents themselves.

There has been much speculation as to what consultant practices are likely to lead to successful consultee-delivered programmes. For example, in an account of effective parent-training practices (Leach 1986), some general principles for intervention design were described. Amongst these, consultants were advised to choose

1effective, pre-tested, pre-packaged procedures that are demonstrably the most suitable for the problem presented,

2procedures which were minimally intrusive and maximally consonant with the people involved,

3procedures that were readily understood and which required the least amount of training,

4procedures that could be integrated in the mediator’s general life so as to be maintained for a sufficient time to reach the goals of the intervention.

It was also suggested that a collaborative, collegial style of consultation might involve consultees to a greater extent than a unidirectional, ‘expert’ style. Similar ‘rules of thumb’ have been described for improving the effectiveness of consultations with teachers. They have been useful reminders that full account needs to be taken of the mediator’s perspective in plans for intervention if mediator commitment and compliance is to be maximized.

More collaborative interchanges, carefully matched programmes, and fewer unthinking applications of behavioural packages may seem obvious ways to increase consultee satisfaction and commitment. However, until fairly recently, there has been little research to support or disconfirm these views. Fortunately this is now changing. Reimers et al. (1987), for example, reviewed twenty studies completed since 1980 which have addressed aspects of the mediator acceptance and compliance problem. In brief, they found that several factors related to consultees’ ratings of an intervention’s acceptability. These were

1the severity of the problem behaviour,

2the time needed to implement a procedure,

3the procedure’s perceived effectiveness,

4the type of treatment recommended (i.e. those designed to increase appropriate behaviour vs. those designed to decrease inappropriate behaviour,

5the extent to which the proposed intervention plan was understandable.

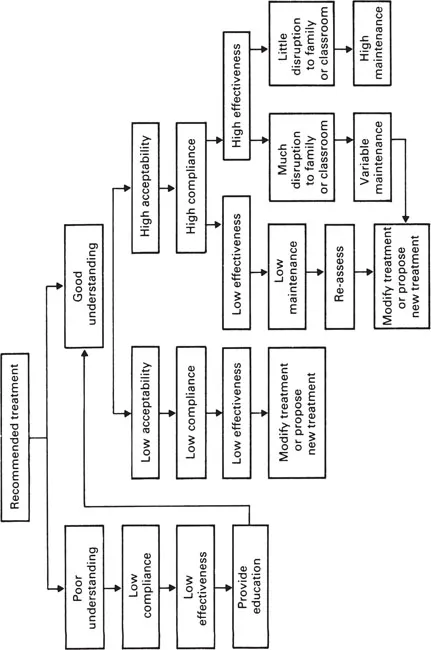

In general, they found that higher ratings of acceptability were more likely the greater the severity of the problem, and the less the time required to implement the intervention procedures. The same was true for effective, well-understood and positive (as opposed to reductive) interventions. Reimers et al. end their review with a useful model which highlights some relationships between these variables. This is reproduced in Figure 1.1.

Witt (1986) summarized research which has examined factors related to teacher satisfaction with behavioural interventions. He pointed out that effectiveness of treatments is not as important as perceived effectiveness, and that treatments which appeal to teachers’ values and common sense appear to be adopted widely despite the absence of published data to support them (see also Somerville and Leach, forthcoming). Other factors related to satisfaction have been identified as preferences for low time, personnel and material costs, lack of ecological intrusiveness, and use of pragmatic descriptions rather than behavioural jargon. Quite clearly, as Happe (1983: 33) nicely put it: ‘The plan that requires the consultee to become a timer-setting, data-taking, token-counting, head-patting octopus has a very low probability of implementation and maintenance’.

On the whole, simulation research of the type described by Reimers et al. and Witt provides support for the collaborative, mini-max approach to planning behavioural interventions (see Leach, forthcoming) where consultant and consultee share equally the referred problem, and the procedures required for its resolution, and strive for the best match between intervention, the consultee, and the consultee’s setting as an approach which may increase consultee acceptability and maintenance of effort. Support for this approach also comes from studies employing such an approach in school settings (Medway 1979; Tunnecliffe et al. 1986). More to the point, it is the implementation of home-based reinforcement programmes for children’s behaviour in school that exemplifies the approach in action to a nicety.

Home-based reinforcement (H-BR) programmes

In the school context, H-BR programmes are essentially frequent, teacher-completed ratings of children’s behaviour in class which are subsequently paired with parent-controlled differential reinforcement at home. A growing number of experimental studies have shown them to be effective and cost-efficient in a variety of educational settings (including regular and special, kindergarten, primary and secondary schools), and across a variety of pupil behaviours (such as attention-to-task, task completion, reading and homework). It is not the intention here to describe this research. Most of the studies have been included already in comprehensive reviews such as those by Atkeson and Forehand (1979) and Barth (1979). Suffice it to say that well-run H-BR programmes have been found to be robust, non-intrusive, flexible interventions which capitalize on the strengths of both teachers and parents. It is largely because of their relative simplicity and minimal disruption to existing routines, that they are readily adapted to the collaborative, behavioural problem-solving model of consultative practice sketched out earlier. It is also likely that their interest for practitioners lies not so much in the novelty of their behavioural components, as through this potential for more effective consultative practice with teachers and parents.

Figure 1.1 The possible relationship between mediator understanding, acceptability and compliance and the effectiveness of behavioural programmes.

Source : Reimers et al. 1987.

Establishing a H-BR programme

Student selection

Invariably there are children who, for various reasons, are identified by school personnel as ‘problem students’. They may often not attend class or they arrive late. They may be children whose behaviour is socially inappropriate or disruptive, who fail to attend to instruction or complete assignments, or who for various reasons fall behind others in their academic performance. H-BR programmes can be targeted at changing any one or more of these kinds of behaviours. They can also be applied to single students or large groups; they can involve one or many teachers; they can be conducted within one school or across a number of schools.

The choice of suitable students for a programme is determined in some degree by the motivation of their teachers and parents to effect behavioural change. The size and scope of the intervention will depend on the number of referred problems that the consultant has to deal with and the number of teachers and parents wishing to participate. In Gilroy’s (1982) intervention, for example, a total of twenty-four students, ranging in age from 6 to 12 years, were drawn from ten regular classrooms in two primary schools. Given a teacher willing and able to record ratings of students on a regular basis, and a parent willing and able to give and withhold reinforcement contingent upon the ratings, then most common in-class problems may be targeted for change.

The teacher

The teacher’s main responsibilities in a H-BR programme can be summarized as follows:

1To specify between five and ten pro-social and pro-learning behaviours that, where possible, are incompatible with each student’s identified ‘problem’ behaviours (e.g. is on time for class; brings appropriate supplies to lesson; talks in class at appropriate times; attends to class work; completes assignments set).

2To write the behaviour on cards for each student.

3To give the cards to the students with a full explanation of their content.

4To mark each student’s card when it is presented after a prearranged period indicating, in an unbiased and objective manner, whether or not each listed behaviour has been observed during that period.

5To return the cards at the end of the pre-arranged period to the students concerned and give social reinforcement for each positive behaviour recorded.

6To check each card from the previous day for a parent’s signature (to prove that it has been seen at home) and to retain the cards in a folder.

7(Optional) To record the total number of positive ratings earned by a student each day and plot the results on a graph.

The consultant’s role is to facilitate the completion of these tasks by working collaboratively with the teacher. Sometimes teachers will define behaviours clearly and draw up the cards with little guidance other than that from a how-to-do-it manual or a brief interview. If this is not sufficient, the consultant might observe students to help define the problem behaviours more precisely or demonstrate how a card should be designed. Either way, the consultee’s understanding of all the tasks in the programme needs to be checked before it is begun. A three-day trial run is also advisable before the cards are given out to students to iron out operational difficulties.

The main problems to arise at this stage are likely to be the listing of too many behaviours that overlap one another (e.g. ‘Is on-task’ and ‘Pays attention to teacher’) and negative behaviours (e.g. ‘Will not sit down at desk when asked’). On the whole, behaviours should be discrete and stated positively. It is also advisable to target a few key academic behaviours, such as ‘completion of work set’, rather than a larger number of subordinate behaviours, such as ‘listens to teacher’s instructions’ or ‘begins work when requested’. The reason for this is that as a student’s behaviour becomes more...