1 Introduction

The social networking site Facebook introduced a feature called Beacon in November 2007. The technology collected data about user activities on Facebook and on external sites (such as online purchases) and reports the results as stories on a newsfeed to the users’ Facebook friends. Beacon collected usage data about users on other partner websites, even if the user is logged out from Facebook and uses this data for personalized and social advertising (targeting a group of friends) on Facebook. The partner sites included, for example, eBay, LiveJournal, New York Times, Sony, STA Travel or TripAdvisor. Users can opt out from this service, but it is automatically activated and legalized by Facebook’s privacy policy. Many users were concerned that Beacon violates their privacy. The civic action group MoveOn (http://www.moveon.org) started a Facebook group and an online petition for protesting against Beacon. Many users joined the online protest, which put pressure on Facebook because the corporation became afraid that a large number of users would leave Facebook, which would mean less advertising revenue and, therefore, less profit. In December 2007, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg wrote an email to all users and apologized. A privacy setting that users can opt out of the usage of Beacon was introduced. However, it was an opt-out solution and not an opt-in solution, which meant that many users will not deactivate this advertising feature, although they had privacy concerns. An online survey among students who used Facebook showed that 59.9 per cent had not opted out of Facebook Beacon (Fuchs 2009a). Facing continued criticism, Facebook shut down Beacon in September 2009. Facebook automatically uses targeted advertising. There is no way to opt out.

We allow advertisers to choose the characteristics of users who will see their advertisements and we may use any of the non-personally identifiable attributes we have collected (including information you may have decided not to show to other users, such as your birth year or other sensitive personal information or preferences) to select the appropriate audience for those advertisements.

(Facebook Privacy Policy; October 5, 2010)

Hearing such stories about Facebook has led many users to believe that Facebook and other profit-oriented social networking sites are large Internet-based surveillance machines (Fuchs 2009a).

The Pirate Bay (http://thepiratebay.org) is a Swedish web platform that indexes BitTorrent files and enables users to search for torrents. BitTorrent is one of the most widely used Internet peer-to-peer file sharing protocols. In December 2009, the Pirate Bay was the 107th most accessed web platform in the world; approximately 1 per cent of all Internet users accessed it within 7 days (data source: alexa.com web traffic statistics, accessed on December 5, 2009). The Pirate Bay has approximately 4 million registered users. This shows that it is a very popular tool. In 2008, Swedish prosecutors filed charges for operating a site that supports copyright infringements against the owners of the Pirate Bay. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry sued the Pirate Bay for copyright infringements in individual lawsuits. In April 2009, the Pirate Bay operators were found guilty. The fixed penalties included prison sentences and fines in the amount of several million Euros. The Olswang Digital Music Survey, conducted by Entertainment Media Research in 2007, showed that 57 per cent of Internet users aged 13–17 and 53 per cent of Internet users aged 18–24 say that they have illegally downloaded music from Internet file-sharing sites (data source: Office of Communications: Communication Market Report 2008, 81; N = 1,721). A total of 66 per cent of Internet users aged 15–24 say that it is morally acceptable to download music for free and 70 per cent say that they do not feel guilty for downloading music for free (Youth and Media survey 2009, N = 1,026, Office of Communications: Communication Market Report 2009, 278). The Swedish Pirate Party achieved more than 7 per cent of Swedish votes at the elections for the European Parliament in 2009. One of its demands is the reform of copyright law:

All non-commercial copying and use should be completely free. File sharing and p2p networking should be encouraged rather than criminalized. Culture and knowledge are good things, that increase in value the more they are shared. The Internet could become the greatest public library ever created.

(Pirate Party Sweden, Principles, http://www.piratpartiet.se/international/ english, accessed on December 5, 2009)

In September 2009, the German Pirate Party achieved 2 per cent of the votes in the German Federal Elections. At the end of 2009, Pirate Parties existed in more than 35 countries. The popularity of Pirate Bay and the relative success of Pirate Parties, on one hand, and the legal measures taken by the recording industry and the film industry, on the other hand, show that there is a fundamental conflict of interests between many young Internet users and the media industry.

In October 2009, student protests against the commodification and economiza-tion of higher education emerged at all Austrian universities. The students squatted lecture halls and demanded more public funding for higher education and the introduction of democratic decision-making structures in the universities. The protests spread to other countries such as Germany and Switzerland. The students made use of social media such as Facebook and Twitter for organizing and communicating their protests (see http://www.unibrennt.at). They also used Internet live video streaming for transmitting the discussions in the squatted lecture halls to the public. At several universities, the debate emerged whether Internet live streaming brings primarily public support or poses the danger that the planning of protest activities is monitored and that as a result protests will be disrupted by political opponents. A solution that was taken at some universities was that the Internet live stream was turned off when crucial organizational debates were conducted but apart from that remained online.

Neda Agha-Soltan, a 27-year-old Iranian woman, was shot on June 20, 2009, by Iranian police forces during a demonstration against irregularities at the Iranian presidential election. Her death was filmed with a cell phone video camera and uploaded to YouTube. It reached the mass media and caused worldwide outrage over Iranian police brutality. Discussions about her death were extremely popular on Twitter following the event. The Iranian protestors used social media such as Twitter, social networking platforms or the site Anonymous Iran for co-ordinating and organizing protests.

The newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson died after being beaten to the ground by British police forces when he watched the G-20 London summit protests as a bystander on April 1, 2009. The police claimed first that he died of natural causes after suffering a heart attack. However, a video showing police forces pushing Tomlinson to the ground surfaced on the Internet, made its way to the mass media and resulted in investigations against police officers.

Austria and Ireland have two of the most highly concentrated newspaper markets in the world (Hesmondhalgh 2007, 173). The Herfindahl index allows measuring market concentration:

hi: absolute value of the reach achieved by media group number i

H > 0.18: high degree of concentration

0.18 < H < 0.10: medium degree of concentration

H < 0.10: low degree of concentration

(Heinrich 1999, 230f.)

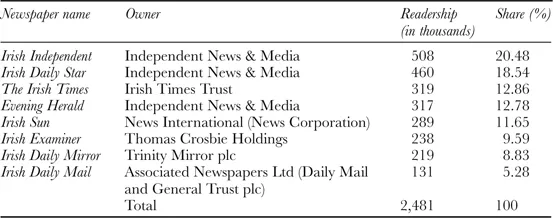

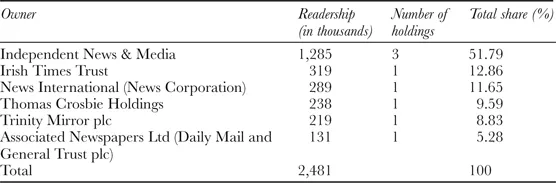

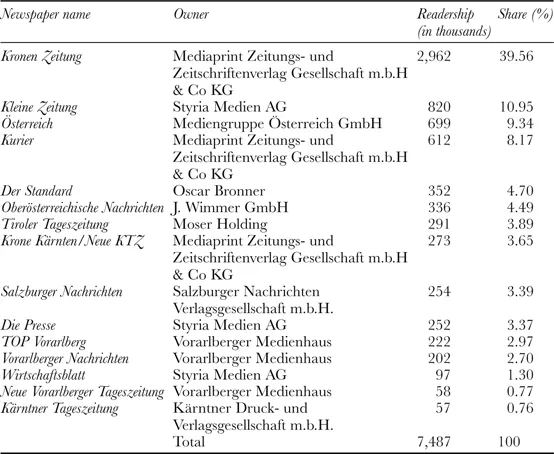

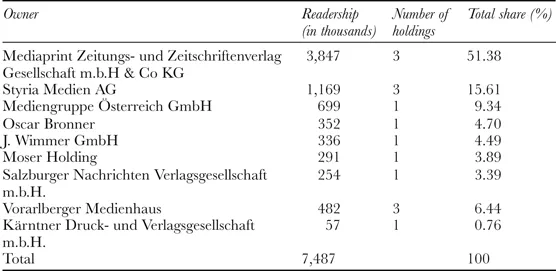

Tables 1.1–1.4 show the readership shares of daily newspapers in Ireland and Austria and a grouping by ownership groups.

The Independent News & Media group controls more than 50 per cent of the Irish newspaper readership and the Mediaprint group more than 50 per cent of the

Table 1.1 Readership of daily and evening newspapers in Ireland

Source: Joint National Readership Survey 2007/2008.

Table 1.2 Readership of daily and evening newspapers in Ireland structured by ownership groups

Table 1.3 Readership of newspapers in Austria

Source: Media-Analyse 2007/2008.

Austrian newspaper readership. The Herfindahl index is H = 0.318 for Ireland and H = 0.308 for Austria. This shows that the newspaper markets in Ireland and Austria are very highly concentrated.

I see power as ‘transformative capacity’, the capability to intervene in a given set of events so as in some way to alter them (Giddens 1985, 7), the ‘capability to effectively decide about courses of events, even where others might contest such decisions’ (ibid., 9); and domination as the employment of means of coercion for influencing the course of events against the will of others. Power is a fundamental process in all societies; domination is a form of coercive asymmetric power relationship between dominant groups or individuals and dominated groups or individuals. Given these definitions, the examples just given show that the media in contemporary society are fields for the display of power, counter-power, domination and sites of power struggles (for a discussion of communication power see Castells 2009; Fuchs 2009b). Facebook controls millions of personal user data that it makes use of to accumulate capital. Capital is a form of economic power; the Internet is a communication power tool that Facebook uses to accumulate economic power. Facebook users cannot directly influence Facebook’s management decisions and policies, so there is an asymmetric power relation between Facebook and its users. However, the example shows that Facebook users have tried to exert counter-power against Facebook’s domination by making use of cyberprotest. The multimedia industry makes money profit by selling media products. File sharers argue that a democratic media structure requires that media products should be freely available to all and, therefore, engage in sharing and downloading such goods over the Internet. The interests of these two groups conflict: the media industry tends to see file sharers as thieves of private property who negatively impact their profits, and file sharers tend to see the media industry as exploiters of the cultural commons. Legal suits and continuous downloading are practices that shape the power struggle between these two groups. This struggle is oriented on setting the conditions for the access to cultural goods. The Internet is a field of conflict in this power struggle. The protesting Austrian students perceived the lack of public funding for higher education and undemocratic decision-making structures within universities as forms of domination that they questioned and that they wanted to transform. They made use of social media for exerting counter-power against dominant structures that negatively impede their conditions of studying and living. Also, the examples of the use of social media in Iran and the United Kingdom show that the Internet and mobile phones can be used as tools for exerting counter-power against domination. The examples of the Irish and Austrian newspaper markets illustrate that media concentration is a concentration of economic capital in the hands of dominant corporations who have the power to influence public opinions, policies and consumer decisions.

Table 1.4 Readership of daily and evening newspapers in Austria structured by ownership groups

The media are tools for exerting domination, power and counter-power; they are power structures themselves and spaces of power struggles. Critical media and information studies (CMIS) conduct analyses of the power and domination structures of the media. The overall aim of this book is to discuss what it means to study the media and technology in a critical way. Information and communication technologies have transformed the ways we live, work, communicate, inform ourselves, engage in social relationships, form values, tackle political problems and so on. This book outlines foundations of a critical social theory of the media that is applied to example studies. It introduces basic theoretical concepts and questions of a critical theory of the media and explains how critical empirical media research works with the help of case studies.

I am convinced that CMIS needs to operate on three interconnected levels: critical social theory, critical empirical research and critical ethics. CMIS consists of a critical theory of the media and information, critical media and information research and critical media and information ethics. On the basis of this distinction, this book consists of three parts: Part I (Theory) discusses theoretical foundations, Part II (Case Studies) provides example case studies and Part III (Alternatives) discusses potential alternatives to dominative media structures. CMIS is based on the insight that academia is not separate from politics but that political interests in heteronomous societies always shape academic knowledge production. If this is the case, then it is impossible for academic knowledge to be value-free, neutral and apolitical. The claim that academia should remain apolitical is itself an ideological claim that frequently legitimates positivistic and uncritical research, which celebrates society as it is and wants to delegitimize critical studies that aim at contributing systematic knowledge to the transformation of structures of domination into structures of co-operation and participation. CMIS is deliberately normative and partial; it supports and wants to give a voice to voiceless and oppressed classes of society.

The task of this book is to ground foundations for the analysis of media, information and information technology (IT) in twenty-first century information society. Theoretical and empirical tools for CMIS will be introduced. I discuss which role classical critical theory can play for analysing the information society and the information economy. I also analyse the role of the media and the information economy in economic development, the new imperialism and the new economic crisis. The book critically discusses transformations of the Internet (‘web 2.0’, ‘social media’ and ‘participatory media’), introduces the notion of alternative media as critical media and shows which critical role media and IT can play in contemporary society.

Part I (chapters 2–4) deals with theoretical foundations of CMIS. Chapter 2 focuses on how a critical theory of society should be conceived today and why such a theory is needed. It focuses on the role of base and superstructure in critical theory, the role of classical critical theory (Marx, Marcuse, Bloch, Horkheimer, Adorno, etc.) for contemporary critical theory and the difference between instrumental and critical theory. The role of the debates on public sociology (Michael Burawoy and others) and recognition/redistribution (Nancy Fraser, Axel Honneth) for contemporary critical theory are discussed. Furthermore, three different understandings of what it means to be critical are identified, various definitions of critical theory are compared and a definition of critical theory that has an epistemological, an ontological and an axiological dimension is suggested. The role of dialectical philosophy for critical theory is discussed.

In chapter 3, the theoretical context and a typology of CMIS are elaborated. Critical studies of media and information are distinguished from other forms of studying these phenomena. A typology of critical media and communication studies is constructed. Example app...