- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Excavations At Ur

About this book

First published in 2010. Sir Leonard Woolley was an archaeologist and this book is about his dig at Ur, which is the subject of this classic work, inspired Agatha Christie's Murder in Mesopotamia. When Woolley began work at Dr, little was known about the early civilizations of Mesopotamia. His work at Dr over twelve years, which included the excavation of royal tombs, the discovery of the gold jewellery of Queen PuAbi and the excavation of the famous ziggurat, allowed scholars to reconstruct the civilization of Sumer in the 3rd century B.C.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

VI

The Third Dynasty of Ur

FOR a hundred years, from 2112 to 2015 B.C., under the five kings of the Third Dynasty, Ur was the capital of a great empire and its rulers were at pains to make it a centre worthy of its political pre-eminence. We very seldom excavated the ruins of a temple without finding some record of that period; either it had originally been founded or it had been restored by some one king of the Third Dynasty. Ur-Nammu, the first of his line, was particularly active as a builder. ‘For Nin-gal his Lady Ur-Nammu the mighty man, King of Ur, King of Sumer andAkkad, has built her splendid Gig-par’, ‘For Inanna the noble lady … Ur-Nammu has built Esh-bur, her beloved temple’, ‘For Nannar the Lord of Heaven’, ‘For Anu King of the gods’, ‘For Nine-gal his Lady’ and so on; it is a formidable list of works undertaken by the new ruler. His reign was not a long one, only eighteen years, and did not suffice for the programme on which he embarked; the Ziggurat itself and E-khursag the Palace were begun by him but finished by his son, and in some cases either haste or economy led him to construct in mud brick only and it was left to his successors to pull down the rather shoddy walls and rebuild in baked brick. Certainly by the time the Third Dynasty was drawing to its close the city of Ur was crowded with magnificent monuments testifying to the wealth and piety of its kings; it was but natural that when Ibi-Sin, the last of Ur-Nammu's line, was defeated by an alien enemy those monuments should be specially signalled out for destruction. With the exception of the Ziggurat there are very few Third Dynasty buildings of which the walls still stand up above ground level; when the time came to restore the ruined temples it was a case not of patching but of pulling down all the old work and rebuilding; it is only in the foundations that we find the stamped bricks bearing the names of the Third Dynasty founders.

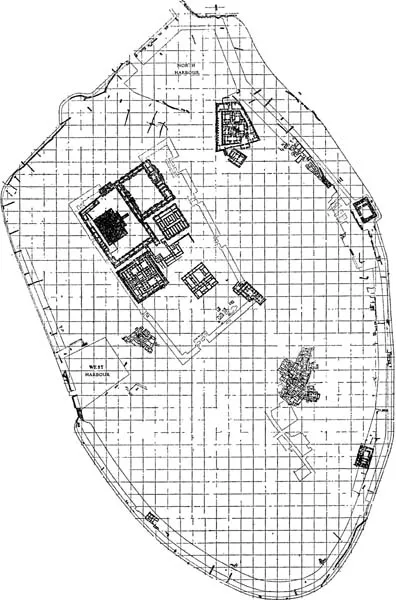

The inscriptions tell us that Ur-Nammu built the walls of Ur ‘like a yellow mountain’. The walled city (Fig. 6) was in shape an irregular oval, measuring about eleven hundred and thirty yards in length by seven hundred and fifty yards in width, and was surrounded by a wall and rampart. The rampart was of mud brick built with a steeply-sloping outer face; the lower part of it was in fact a revetment against the side of the mound formed by the ruins of the older town, but the upper part of it extended inland over the top of the ruins to make a solid platform from twenty-five to thirty-five yards wide rising twenty-six feet above the level of the ground at the rampart's foot while its back stood only five feet above the ground-level inside the city. Along the top of this ran the wall proper, built of burnt bricks; where the rampart was narrowest one had simply the wall with a berm in front of it and behind it a passage for the manoeuvring of troops; where it broadened out it was because here there was a temple or other public building standing on the rampart; such might be incorporated in the system of defence, its outer wall linking up with the city wall and its roof serving as a tower. This massive fortification was further strengthened by the fact that the river Euphrates (as can be seen from the sunken line of its old bed) washed the foot of the western rampart while fifty yards from the foot of the eastern rampart there had been dug a broad canal which left the river immediately above the north end of the town, so that on three sides Ur was ringed with a moat and only from the south could be approached by dry land. It was a colossal work and must have seemed to the builder impregnable, but it was to fall in the end; the rampart, backed by a solid mass of earth, could not be violently overthrown and although in places wind and rain have weathered it almost all away yet we seldom failed to find at least the lower part of its worn and battered face; but of Ur-Nammu's wall not a trace remained. We would come on examples of the very large bricks, specially moulded and inscribed with the king's name and titles,

Fig. 6. Plan of the City of Ur showing the principal sites excavated

re-used in some later building, but none of them were in situ; just because the defences of Ur had been so strong the victorious enemy had dismantled them systematically, leav-ing not one brick upon another.

With the Ziggurat it was very different. Of all the great staged towers which characterized the cities of Sumer that of Ur is the best preserved, and it is for the most part the original work of Ur-Nammu. Here a few words of explanation are called for. The Ziggurat is a peculiar feature of Sumerian architecture which can now be traced back to the earliest times, to the period of the chalcolithic al ‘Ubaid people. As we have seen, the al ‘Ubaid people (whose skull formation shows them to have resembled what is called Caucasian man) had cultural affinities with Elam and therefore presumably came down into the Euphrates valley from the east, came, that is, from a hilly country; like all people who live in a mountainous land they would naturally associate their religion with the land's outstanding features, and as a matter of fact the Sumerian gods are often represented as standing upon mountains and would accordingly be worshipped upon ‘high places’. The immigrants to Lower Mesopotamia found themselves in a vast level plain where there was no hill on which god could be properly worshipped, and art therefore had to make good the deficiencies of nature. Here even a private house, if it was to be safe-guarded against the annual inundations, needed to be raised on some sort of platform, and that being so the solution of the religious difficulty was not far to seek—the platform merely had to be made taller. In every town therefore which was big enough to warrant the effort the inhabitants built a ‘high place’, a tower rising up in stages and crowned by the town's principal shrine; they used ‘bricks instead of stone and slime (bitumen) had they for mortar’, and to their work they would give such a name as ‘the Hill of Heaven’ or ‘the Mountain of God’. This was the Ziggurat. Of them all, the biggest and the most famous was, in course of time, the Ziggurat of Babylon, which in Hebrew tradition became known as the Tower of Babel; it was entirely destroyed by Alexander the Great, but its groundplan survives and shows that it was but a repetition on a slightly larger scale of the Ziggurat of Ur; and it too was built by Ur-Nammu.

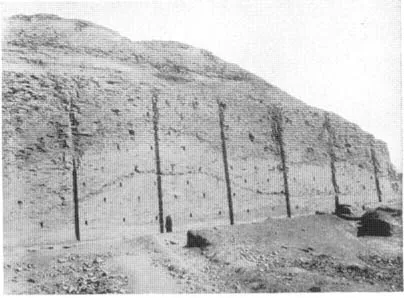

The site of the Ziggurat of Ur was fixed by ancient tradition. I have spoken already of the ziggurats of the Jamdat Nasr and Early Dynastic periods; what Ur-Nammu did was to rebuild over these, probably incorporating their remains in the core of his new structure. The site was in the west corner of the Temenos called E-gish-shir-gal or Sacred Area of the city; the king rebuilt the enclosing wall of the Temenos (which formed the second line of the defences of Ur) and although very little of that wall survives we found traces of it sufficient to give us its outline and the proof that it was indeed the work of Ur-Nammu. The Sacred Area as a whole was dedicated to the Moon-god Nannar and his wife Nin-gal—at least, this seems to be the case, for Ur-Nammu expressly states on his brick-stamps that he built it for Nin-gal, while other inscriptions of the Third Dynasty speak of it as belonging to Nannar; presumably the two deities shared it in common. But the north-east end, called E-temen-ni-il, was the peculiar property of the Moon-god; here, in the west corner, rose the terrace on which the Ziggurat stood, and in front of the terrace, to the north-east, occupying about two-thirds of the terrace length and extending to the far wall of the Sacred Area, was the Great Court of Nannar; the great court was low-lying, actually sunk somewhat below the general level of the Temenos, and there must have been a flight of steps in the monumental gateway that gave access from it to the terrace, for the latter was raised three feet above Temenos level. The terrace was surrounded by a massive double wall of mud brick with intramural chambers; much of it had gone, but on the north-west side it was well preserved, standing still to a height of five and a half feet. It was of mud brick, built against the core of the old First Dynasty terrace wall; the front sloped steeply back (the angle was 35 in ioo) and was relieved by shallow buttresses sixteen feet wide and little more than a foot deep which must be considered decorative rather than constructional, since they can have added nothing to the building's strength [Plate 17b]. The face of the wall was smoothly rendered with mud plaster; much of this had fallen away and we very soon cleared off the rest, for beneath the plaster there was a dramatic discovery to be made. At regular intervals of two feet there appeared the small rounded heads of clay ‘nails’ driven into the mud mortar between the brick courses; these were ‘foundation-cones’ and on the ‘nail's’ stem was the inscription ‘For Nannar the strong bull of Heaven, most glorious son of Enlil, his King, has Ur-Nammu the mighty man, King of Ur, built his temple, E-temen-ni-il’. Such cones were familiar enough as objects on Museum shelves, but now for the first time we saw them in position just as the builders had set them four thousand years before. That they should be found in situ is of course most important scientifically, for we not only learn that a particular king built a particular temple, but they positively identify a building which we have excavated and they give it a positive date; but at the same time one felt a quite unscientific thrill at seeing those ordered rows of cream-coloured knobs which even the people of Ur had not seen when once the terrace wall was finished and plastered.

The excavation of the Ziggurat itself was a formidable task. In the middle of last century Mr. J. E. Taylor, then British Consul at Basra, was engaged by the British Museum to investigate some of the ancient sites of southern Mesopotamia, and amongst others he visited Ur, in those days a place difficult and dangerous of access. Struck by the obvious importance of one mound, which from its height, overshadowing all the other ruins, he rightly judged to be the Ziggurat, he attacked it from above, cutting down into the brickwork of the four corners. The science of field archaeology had not then been devised and the excavator's object was to find things that might enrich the cases of a museum, while the preservation of buildings on the spot was little considered. To the greatest monument of Ur Taylor did damage which we cannot but deplore to-day, but he succeeded in his purpose and at least made clear the importance of the site whose later excavation has so well repaid us. Hidden in the brickwork of the top stage of the tower he found, at each angle of it, cylinders of baked clay on which were long inscriptions giving the history of the building. The texts date from about 550 B.C., from the time of Nabonidus, the last of the kings of Babylon, and state that the tower, founded by Ur-Nammu and his son Dungi, but left unfinished by them and not completed by any later king, he had restored and finished. These inscriptions not only gave us the first information obtained about the Ziggurat itself, but identified the site, called by the Arabs al Mughair, the Mound of Pitch, as Ur ‘of the Chaldees’, the biblical home of Abraham.

Taylor's excavations did not go very far. Those were the days when in the north of Mesopotamia Rawlinson was unearthing the colossal human-headed bulls and pictured wall-slabs which now enrich the British Museum, and, dazzled by such discoveries, people could not realize the value of the odds and ends which alone rewarded the explorer in the south, and the work at Ur was therefore abandoned. Towards the close of the century an American expedition again attacked the top of the mound and exposed some of the brickwork, but apart from that apparently fruitless attempt at excavation the site was deserted and what showed of the upper stages of the Ziggurat was left to the mercies of the weather and of Arab builders in search of cheap ready-made bricks; when British troops advanced to Mughair in 1915 only a few ragged bricks could be seen protruding from the top of a huge mound of undisturbed sand and rubble up whose gently sloping sides a man could ride on horseback. In 1919 Dr. H. R. Hall initiated the real excavation of the monument and cleared part of the south-east end down to the level of the terrace floor and discovered that the lower part of the brick casing, protected by the rubbish heaped against it, was wonderfully well preserved. It was manifest that the work begun by Hall must be continued by the Joint Expedition, and we started on it almost at once, but it was a task that could not be completed in a hurry.

The amount of rubbish which had to be removed was very great, running into thousands of tons, all of which had to be lifted in small baskets and then carried by our light railway to a safe distance where it would not hamper later operations. In this mass of fallen brick and wind-blown sand there were

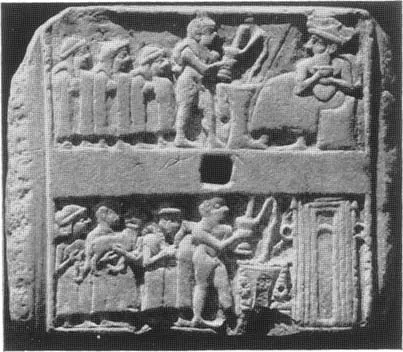

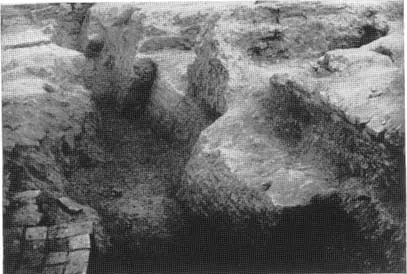

Plate 17

a. Limestone relief of sacrifice, Lagash period

b. Ur-Nammu's wall supporting the Ziggurat Terrace

Plate 18

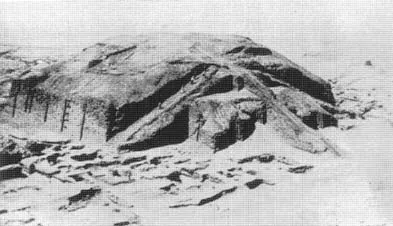

The Ziggurat of Ur-Nammu; back and front views

no objects of any sort to be found, so that, until we were down to floor level, the job was mere navvy work unimpeded by any considerations of archaeological method, and actually the end of our 1923–4 season saw the great building standing free of the rubbish which had shrouded it for so many centuries. Of course a vast amount remained to be done on the surrounding buildings, but I fondly imagined that our work on the tower itself was finished, and taking advantage of the assistance of Mr. F. G. Newton, the most experienced of archaeological architects, ventured to reconstruct on paper the Ziggurat as it had originally been.

The reconstruction was wrong. Because of all the zig-gurats in Iraq that of Ur seemed to be the best preserved the Government had very properly seen to its protection and we had been instructed that on no account were we to move any of the brickwork remaining in situ. The cylinders found by Taylor told us that Ur-Nammu and his son Dungi had between them built the staged tower and that Nabonidus had restored and finished it, but they did not say that other kings too had worked upon it. A fair proportion of the burnt bricks of Ur-Nammu bore his stamp, and so did some of Nabonidus' bricks, but the vast majority of the bricks bore no name. We were in our early days at Ur and had still everything to learn; for us a plain brick was just a brick, and we had not got the experience to decide by its measurements and proportions to which period of history it ought to be assigned. Consequently when, high up on the Ziggurat, we brushed the surface of the bricks which we might not move (and the stamps were most often on the under side!) we assumed, or I assumed, that what did not belong to Nabonidus necessarily belonged to the Third Dynasty, and when it came to working out the reconstruction of the Third Dynasty building some of the evidence on which I relied was brickwork of an entirely different period. Later on, of course, I recognized that this first attempt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- The Kegan Paul Library of Archaeology and History

- Full Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- PLATES

- ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

- Introduction

- I. The Beginnings of Ur, and the Flood

- II. The Uruk and Jamdat Nasr Periods

- III. The Royal Cemetery

- IV. Al ‘Ubaid and the First Dynasty of Ur

- V. The Dark Ages

- VI. The Third Dynasty of Ur

- VII. The Isin and Larsa Periods

- VIII. The Kassite and Assyrian Periods

- IX. Nebuchadnezzar II and the last days of Ur

- Appendix: The Sumerian King-List

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Excavations At Ur by Woolley,Sir Leonard Woolley,Sir Leonard Woolley Woolley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Egyptian Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.