- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Membrane-Distillation in Desalination

About this book

Membrane-Distillation in Desalination is an attempt to provide the latest knowledge, state of the art and demystify outstanding issues that delay the deployment of the technology on a large scale.

It includes new updates and comprehensive coverage of the fundamentals of membrane distillation technology and explains the energy advantage of membrane distillation for desalination when compared to traditional techniques such as thermal or reverse osmosis.

The book includes the latest pilot test results from around the world on membrane distillation desalination.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Scienze fisicheSubtopic

Chimica industriale e tecnica1

The Water Nexus and Desalination

1.1 Introduction: The Twenty-First Century Context for the Pursuit of Sustainable Water Resources

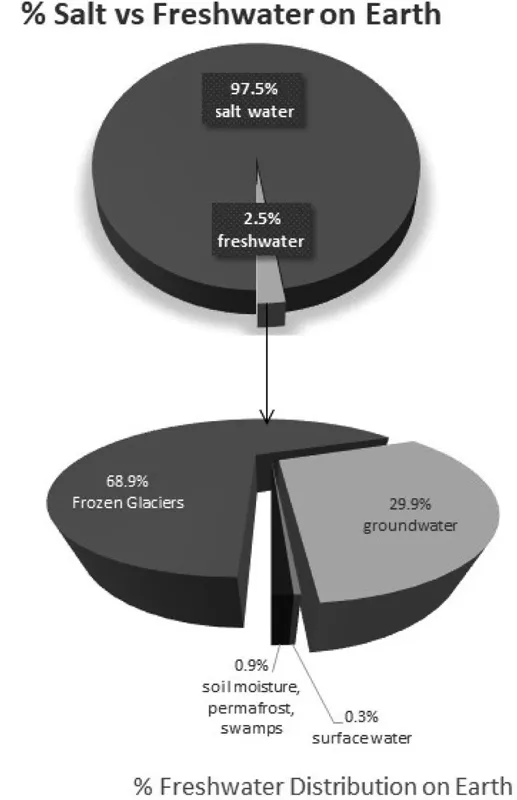

Humanity embarked on the twenty-first century facing a number of challenges leaving politicians, visionaries and academics pondering on elusive solutions for a long time to come. Some such major challenges include water resources, energy, food security and population. This is by no means an exhaustive list. However, the four challenges mentioned are intimately related. By far, availability and access to clean freshwater constitute the major concern to decision makers globally. Indeed, the inexorable increase in the world population over the past decades put a considerable strain on Earth’s freshwater. While planet Earth has an immense salt water inventory in the form of oceans and seas, freshwater constitutes a mere 2.5% of the global total water and from this fraction, nearly 69% of freshwater is locked as frozen glaciers and permanent icecaps, leaving just over 30% of freshwater available as groundwater and 0.3% of freshwater available as surface water. Surface freshwater constitutes a tiny 0.3% of freshwater available and the remaining 0.9% are accounted for as soil moisture, permafrost and swamps. This remarkable and striking estimate reported by Igor Shiklomanov [1] still remains a valuable reference for the global freshwater inventory of planet Earth. Figure 1.1 depicts Earth’s global water and freshwater distribution.

Unlike other natural resources, water circulates naturally according to the global hydrological cycle offering the possibility to recharge natural and man-made water catchments. However, according to Oki and Kanae [2], it is the flow of water that should be the focus rather than the stock in the assessment of water resources. Oki and Kanae [2] also pointed out that due to the long time it may take to recharge groundwater reservoirs naturally to their original volume stored, if ever, groundwater has sometimes been called “fossil water.”

FIGURE 1.1

Earth’s global water and freshwater distribution.

Earth’s global water and freshwater distribution.

This is particularly significant when groundwater is being withdrawn in many parts of the world at a rate that exceeds natural recharging [3,4,5] and that globally, about 70%–80% of the total water consumed is used in agriculture [1,6].

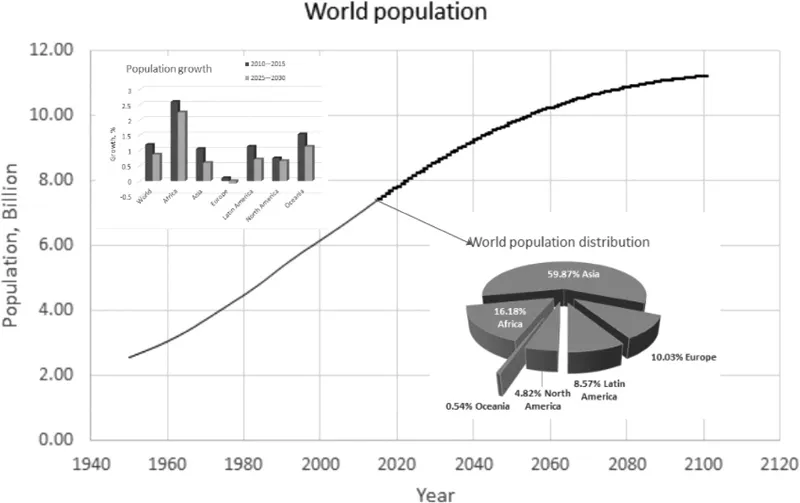

The surge in freshwater consumption is primarily due to an increasing world population that needs food from agricultural activity, industrial activities and urban/rural development to maintain or improve its lifestyle. The most recent United Nations population census [7] depicts an unprecedented upward trend in the past decades, reaching 7.63 billion in 2017 and projected to reach over 10 billion past the 2050 horizon. Figure 1.2 shows the world population trend from the 1950s to the 2100 horizon. It can be seen that the major fraction of the world population is currently (2017) located in Asia (59.87%), followed by Africa (16.18%), Europe (10.03%), Latin America (8.57%), North America (4.82%) and finally Oceania (0.54%). The population growth in Figure 1.2 indicates that the global population will continue an upward trend with the exception of Europe where a negative growth may be experienced past the 2025 horizon. Because the uneven distribution of renewable freshwater reserves (RFWR) has been somewhat exacerbated by the climate system, most regions in the world, regardless of the status of economic development or wealth, have been affected by water shortages intermittently or permanently. Consequently, a measure of water scarcity has been put forward in the form indices commonly called water scarcity indices. These indices have been reviewed by Brown and Matlock [8]. However, the simplest water scarcity index covered by Oki and Kanae [2] has been used to map water-stressed regions in the world. This water scarcity index is represented by the following equation:

FIGURE 1.2

The world population trend from the 1950s to the 2100 horizon.

The world population trend from the 1950s to the 2100 horizon.

(1.1) |

TABLE 1.1

Water Scarcity Scale

Rws < 0.1 | No water stress |

0.1 ≤ Rws < 0.2 | Low water stress |

0.2 ≤ Rws < 0.4 | Moderate water stress |

Rws ≥ 0.4 | High water stress |

where Rws is the water scarcity index, W is the annual abstraction, S is the desalinated water and Q is the annual available water. From this definition, a water scarcity scale system [9] has been proposed, as seen in Table 1.1 and used to identify regions with Rws equal or greater than 0.4. These regions include northern China, the region bordering Indian and Pakistan, the whole of the Middle-East and North Africa (MENA) and much of the western regions of the United States of America. Parts of southern Europe also suffer from water scarcity.

Tables 1.2 and 1.3 show the water withdrawal by source and usage sector in the MENA region and water withdrawal by sector (including desalination) as % of total, respectively [6].

Table 1.2 shows that the Arabian Gulf region has one of the highest groundwater consumption in the world for agriculture while Africa has the highest proportion of its freshwater resource used for agriculture. The world average for water usage in agriculture is 69%. The large water consumption for agriculture and indirectly for food production in all forms led to the introduction of a particular footprint called “water footprint” (akin to the carbon footprint) [10,11,12]. Ironically, most healthy foods (vegetables) have a rather large water footprint [13,14]. This has profound implications on the meaning of sustainability of freshwater supplies. In other words, water security is a global issue and truly deserves the phrase “water nexus” [15,16,17,18].

Given the status of the water scarcity globally, how can we increase the water supply when the hydrological water cycle is not only finite, but also exacerbated by an increasing world population and an erratic climate pattern that does not spare any region in the world?

TABLE 1.2

Water Withdrawal by Source and Usage Sector in MENA Region

1(2002) 2(2005) 3(2003) 4(2012) 5(2010) 6(2011) 7(2004)

a Combined ground and surface.

TABLE 1.3

Water Withdrawal by Sector (including Desalination) as % of Total

Agriculture | Municipal | Industry | |

World | 69 | 19 | 12 |

Africa | 81 | 15 | 4... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Author

- 1. The Water Nexus and Desalination

- 2. Membrane Distillation Desalination Principles and Configurations

- 3. Membranes for Membrane Distillation in Desalination

- 4. Membrane Distillation Module Design

- 5. Membrane Distillation Performance Analysis

- 6. Membrane Fouling and Scaling in Membrane Distillation

- 7. Membrane Improvement in Membrane Distillation

- 8. Modeling of Membrane Distillation

- 9. Low-Carbon Energy Sources for Membrane Distillation Processes for Desalination

- 10. Conclusions and Future Horizons for Membrane Distillation Desalination

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Membrane-Distillation in Desalination by Farid Benyahia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze fisiche & Chimica industriale e tecnica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.