- 166 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1990, Urban Markets looks at how the informal sector of the economy should be encouraged to assist in the alleviation of problems of poverty and unemployment. Despite this rhetoric, few concrete, implementable ways have been developed. This book is concerned with one such potential strategy which the authors consider to be particularly effective: the creation of both built and open markets for very small retailers and wholesalers. Based on experience of observing such markets in several continents, the authors combine a discussion of the theoretical issues surrounding the creation of urban markets with practical hints of how to establish and run them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Markets by David Dewar,Vanessa Watson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction: Urban markets and informal-sector stimulation

Considerable rhetorical emphasis is being placed, in many countries, on the potential role of the informal sector in alleviating poverty and unemployment, and there is a growing call for the ‘stimulation’ of this kind of activity. There is little clarity, however, about precisely how such stimulation should occur. This book focuses on one potential instrument of stimulation: urban markets which cater for small-scale vendors. Specifically, it seeks to provide insights into issues relating to the role, location, physical structure, financing, and administration of such markets. Its origins stem from research initiated in 1980 (Dewar and Watson 1981) into the question of the urban informal sector and its stimulation. In the course of that work it became apparent that the stimulation and facilitation of markets to accommodate small-scale traders and manufacturers represents one significant means of promoting small-scale economic activity in urban areas. It also indicated that the efficacy of markets, and thus their effectiveness as a policy tool, is strongly informed by their location, structure, form, and administration.

To understand the significance of the issue, and the concerns underlying the observations which follow in this book, it is necessary to locate the question of markets in the broader context of informal-sector stimulation.

Informal-sector policies

Over the past few decades, attitudes of policy-makers towards the informal sector have undergone some major changes (Sanyal 1988). Development theorists and policy-makers alike in the 1940s and 1950s regarded the informal sector as the declining remnant of pre-capitalist economies. As such, it was perceived to be an inefficient, backward, irrational, and frequently unhygienic form of economic activity. It was assumed, in keeping with general tenets of the then dominant modernization paradigm, that as the less-developed economies progressed from a ‘traditional’ to a ‘modern’ state, the informal sector would be incorporated into the ‘modern sector’ of the economy and would gradually disappear. In policy terms, there were attempts in many parts of the world, at both central and local levels of government, to restrict the operation of the informal sector and, in particular, to exclude it from residential areas and the main commercial centres of cities.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, both this perception and its associated policy approaches underwent a significant reversal in many countries. In less-developed countries particularly, problems such as poverty, inequality, and unemployment were manifesting themselves in political dissatisfaction, and policy-makers were concerned about finding alternative ways to ameliorate such problems. It was becoming clear, too, that previously accepted, indeed almost unquestioned, approaches to economic development, which assumed that the benefits of economic growth would ‘trickle down’ to the lower income groups more or less automatically, were not always resulting in widespread improvements in welfare levels, particularly amongst the poor. Strategies which consciously promoted a wider distribution of economic benefits and, particularly, greater employment, were required.

A watershed event in this regard was the launching, in 1969, of the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) ‘World Employment Programme’. While acknowledging the need for economic growth, the agency argued that ‘part of the difficulty is structural, in the sense that many of these difficulties will not be cured simply by accelerating the rate of growth’ (International Labour Office 1972: xi). Accordingly, it initiated a series of country-wide studies to evolve employment-orientated strategies of development.

Perhaps the best-known and most influential of these was the Kenya Mission Report (International Labour Office 1972), which advocated an economic-development strategy for that country termed ‘redistribution with growth’. The report identified as a central issue the need to stimulate local demand in order to lay the basis for a broader, less import-dependent economic system. To achieve this, the report placed emphasis on the redistribution of income, the stimulation of rural and agricultural development, the reorientation of industry towards local raw materials and demands, the promotion of labour-intensive practices, the use of appropriate technology, and increased economic self-reliance.

Most significantly for this discussion, however, it identified the informal sector as having the potential to play an important role both in providing employment and in contributing to a reorientation of the economy. As opposed to previous conceptions of the informal sector as a stagnant and undesirable phenomenon, the Kenya Report emphasized that the informal sector, which provided employment for between 28 and 33 per cent of the working population of Nairobi, was by no means unproductive or declining. Instead, the authors argued, it was competitive, labour-intensive, made use of locally produced materials, developed its own technology and skills, and businesses were usually locally owned. According to the report, therefore, it not only played an important part in reducing Kenya’s employment problem, but also helped to serve the lower end of the consumer market without making excessive demands on foreign exchange or imported capital goods. In policy terms, the report recommended the direct encouragement by the government of the informal sector as a partial solution to the problems of unemployment and poverty.

This switch in attitude towards the informal sector was by no means universally accepted in policy terms. In many countries, the perception of it as an aberration and a nuisance has continued. However, the ILO study did have the effect of focusing attention on the phenomenon, and it unleashed, in subsequent years, numerous empirical and theoretical studies on it.

While it is not the intention here to undertake a review of theoretical developments in the field of informal-sector studies, these studies have raised a number of debates and issues which are directly relevant to policy formation in this field. Since this book is about a dimension of policy formation, it is important that the authors’ personal positions on these debates are clarified for the reader from the outset.

Definitional debates

The first debate centres on definition. Over time, many and varied attempts have been made to define the phenomenon of the informal sector, and it is clear that ‘an analytically verifiable definition of the informal sector still remains to be constructed’ (Sanyal 1988: 66). It has, however, become apparent that the definition will properly vary according to the purpose for which, or the philosophical position from which, the definition is being made. One of the central issues which has emerged in the definitional debate is whether the focus of attention should be on the business or activity, or on the household unit. The approach taken here is that, from a theoretical perspective, and in terms of explaining the nature and characteristics of these activities, the household unit is clearly a crucial variable in terms of both income generation and income distribution. However, if the concern is with policy and the impact of outside stimulatory agents and instruments on informal activities, then properly the emphasis is better placed on the economic enterprise.

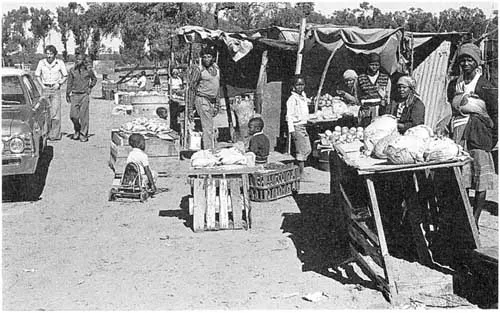

Further, it is misleading, from a policy perspective, artificially to separate informal, small-scale economic activities from larger, more formal ones. They do not operate in separate economic circuits: indeed, they are vitally interrelated. They also have similar economic requirements and respond to similar stimulatory or depressive impulses, although the form of these may vary. From a policy perspective, therefore, the term ‘informal sector’ simply focuses attention on economic enterprises at the bottom end of a continuum ranging from very small to very large businesses. It is used here as a convenience, since the widespread and popular use of the term ‘informal’ conjures up an image of less stable, more oppressed and fragile, and sometimes impermanent economic activities, and these represent the focus of the activities which are central to this work (Plate 1).

Plate 1 Informal selling: Crossroads, Cape Town.

The informal sector is usually viewed as a fragile and impermanent economic activity.

Debates relating to linkages

The second debate stems from a recognition of the numerous and complex linkages which exist between the ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ sectors, and hinges on two questions: first, are the linkages of a benign or exploitative nature; and second, is the lower end of the economic continuum capable of responding to promotional policies or is it not – is it evolutionary or is it involutionary? (Tokman 1978).

Basically the debate has revolved around the question of how capital accumulation takes place in the informal sector. On one hand, it is argued that these activities do generate surpluses unless unduly repressed by the law: in this case it is assumed that the linkages are benign (Weeks 1975, Sethuraman 1981). On the other hand, it has been argued that the informal sector is incapable of significant accumulation because its level of surplus is dictated by the accumulation process in the formal sector: that is, the linkages are exploitative (Bromley and Gerry 1979, Moser 1984).

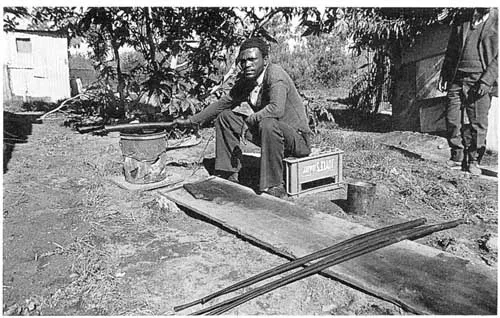

Those who argue in favour of a benign relationship emphasize the crucial role played by the informal sector in the circulation process by being located near customers, by providing credit, by selling in units as required, and by targeting products specifically at the needs of the low-income market (Tokman 1978). The informal sector, therefore, generally serves a specifically poor market and in this sense remains complementary to the formal sector (Plate 2). Its capacity for accumulation can then be enhanced by its access to the expanding markets in the rest of the economy: its growth may be ‘evolutionary’.

Plate 2 Making sjamboks (whips): Crossroads, Cape Town

The informal sector frequently targets products specifically designed for the low-income market. These sjamboks (whips) made in Crossroads, Cape Town, serve as symbols of authority as well as protective instruments in low-income areas.

Those who argue that the relationship between the formal and informal sector is exploitative have generally taken as their point of departure the theory of unequal exchange as fundamental to an explanation of regional inequality. In brief:

The process of accumulation in the developed countries assumes the characteristic that productivity gains are retained within the centres, while simultaneously the gains in productivity registered in the periphery are appropriated through different mechanisms . . . such as . . . international price determination and market control . . . and institutional arrangements fostered by transnational capital.

(Tokman 1978: 1067).

The relationship between the formal and informal sectors is analyzed as a subcomponent of this process, whereby the economic surplus generated in the informal sector is transferred to the formal sector. There are two major mechanisms through which surpluses may be transferred from the informal to the formal sector.

First, the informal sector lacks access to basic resources of production because these resources are monopolized by the formal sector. Thus

the oligopolistic organization of the product markets leaves for informal activities those segments of the economy where minimum size or stability conditions are not attractive for oligopolistic firms to ensure the realisation of economies of scale and to guarantee an adequate capital utilization.

(ibid.: 1069).

Second, the informal sector is forced into a position whereby it must pay higher prices for its purchases, but can only ask lower prices for its outputs, the difference being reaped by the formal sector. Prices of purchases are generally higher because small operators can only buy small quantities and they do not have access to credit facilities, while prices for their products, mostly services, are lower because of the market they depend upon (ibid.). Because the ability of the informal sector to accumulate is thus limited by its relationship to the formal sector, the ability of the informal sector to grow or respond to promotional policies is limited, and the sector as a whole is said to be ‘involuting’.

The question of interconnectivity between small businesses and large, and the implications of this for the evolution or involution of small businesses, is thus an important one. These authors believe that the weight of evidence favours the position taken by Tokman, who questions the simplicity of both the ‘benign relationship’ and ‘exploitative relationship’ schools. The informal sector comprises a great variety and range of enterprises and it is not possible to generalize as to their relationship with the formal sector. ‘The problem’, Tokman says, ‘is to determine how strong the subordination is, and whether there is room left for evolutionary growth.’ (ibid.: 1071). While both prices and markets may indeed be determined outside the informal sector, there are also numerous ways in which the informal sector can maintain a share of the market. Tokman (ibid.: 1073) quotes, in the case of small retail outlets: ‘Location, owner-customer personal relationships, credit, infinite possibilities of product sub-division, permanent presence because of the non-existent “business hours”, etc. . .’. It is evident that in any study of small businesses, a careful disaggregation needs to take place, to determine exactly where the possibilities of expansion or contraction are likely to be.

Nevertheless, there is no intrinsic reason for rejecting the introduction of policies to stimulate this kind of activity. Certainly, it is untenable to suggest, in contexts characterized by high unemployment and an increasing competitive imbalance in favour of larger, ‘formal’ businesses, that the repression of informal sector activities should continue. It can be assumed that if a more facilitative policy towards the informal sector were adopted, it would be possible for a greater number of people to improve their survival chances, or at least to supplement their income, in this way. Similarly, it is sensible to introduce policies which seek to strengthen the relative position of economic co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Urban markets and informal-sector stimulation

- 2 Urban markets: some issues relating to their location, design, and administration

- 3 The empirical foundation

- 4 Market cases

- Bibliography

- Index