- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Theory as Science (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

This book, written by a philosopher interested in the problems of social science and scientific method, and a sociologist interested in the philosophy of science, presents a novel conception of how we should think about and carry out the scientific study of social life. This book combines an evaluation of different conceptions of the nature of science with an examination of important sociological theorists and frameworks. This second edition of the work was originally published in 1982.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Theory as Science (Routledge Revivals) by Russell Keat,John Urry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part one

Conceptions of science

In the following three chapters, we will present a critical analysis of three widely differing conceptions of the natural sciences—positivism, realism, and conventionalism. The analysis will be conducted primarily by reference to Anglo-American philosophers of science who have developed and defended these positions in the twentieth century. These positions have important connections with earlier views in the history and philosophy of science, and also with more general philosophical and intellectual movements. But, first, let us provide a brief outline of the three positions.

For the positivist, science is an attempt to gain predictive and explanatory knowledge of the external world. To do this, one must construct theories, which consist of highly general statements, expressing the regular relationships that are found to exist in that world. These general statements, or laws, enable us both to predict and explain the phenomena that we discover by means of systematic observation and experiment. To explain something is to show that it is an instance of these regularities; and we can make predictions only on the same basis. Statements expressing these regularities, if true, are only contingently so; their truth is not a matter of logical necessity, and cannot be known by a priori means. Instead, such statements must be objectively tested by means of experiment and observation, which are the only source of sure and certain empirical knowledge. It is not the purpose of science to get ‘behind’ or ‘beyond’ the phenomena revealed to us by sensory experience, to give us knowledge of unobservable natures, essences or mechanisms that somehow necessitate these phenomena. For the positivist, there are no necessary connections in nature; there are only regularities, successions of phenomena which can be systematically represented in the universal laws of scientific theory. Any attempt to go beyond this representation plunges science into the unverifiable claims of meta-physics and religion, which are at best unscientific, and at worst meaningless.

The realist shares with the positivist a conception of science as an empirically-based, rational and objective enterprise, the purpose of which is to provide us with true explanatory and predictive knowledge of nature. But for the realist, unlike the positivist, there is an important difference between explanation and prediction. And it is explanation which must be pursued as the primary objective of science. To explain phenomena is not merely to show they are instances of well-established regularities. Instead, we must discover the necessary connections between phenomena, by acquiring knowledge of the underlying structures and mechanisms at work. Often, this will mean postulating the existence of types of unobservable entities and processes that are unfamiliar to us: but it is only by doing this that we get beyond the ‘mere appearances’ of things, to their natures and essences. Thus, for the realist, a scientific theory is a description of structures and mechanisms which causally generate the observable phenomena, a description which enables us to explain them.

We have noted already that, despite their differences, positivists and realists share a certain general conception of science and its objectives. What is common to those philosophers of science we call ‘conventionalists’ is their rejection of these shared attitudes. But their reasons for doing so are varied. It may be argued that observations cannot by themselves determine the truth or falsity of theories, and that no useful distinction between theory and observation can be maintained. Or, that there are no universal criteria for choosing rationally between different theoretical frameworks, and that moral, aesthetic, or instrumental values play an essential part in such choices. More radically, the idea of an external reality which exists independently of our theoretical beliefs and concepts may be rejected. Associated with these different claims are different positive conceptions of science. In all of them, there is a sense in which the adoption of theories is a matter of convention. But ‘conventionalism’, as we use this term, does not denote a homogeneous set of views about science, which can be simply contrasted with positivism and realism. What unites conventionalists is their opposition to the view of science as providing true descriptions and explanations of an external reality, through theories which can be objectively tested and compared by observation and experiment.

So far, these accounts of positivism, realism and conventionalism have been couched, as far as possible, in terms that are not specific to the way in which they have been developed in twentieth-century philosophy of science. For we wish to emphasize that each of these views has a long history in science and philosophy. The realist position, with its emphasis on causal explanations through the discovery of essences, was systematically articulated by Aristotle, developed by various medieval philosophers, and continued through the seventeenth-century scientific revolution and after; for example, in the writings of Locke, who developed an epistemology based on the corpuscularian realism of the science of his time. Positivist philosophy of science was significantly developed in the early eighteenth century, through the work of Hume and Berkeley, with the denial of causal necessity in nature, the defence of a regularity view of causation and explanation, and the rejection of any scientific concepts which went beyond the realm of the observable. Elements of positivism were already present in the writings of medieval philosophers, such as Ockham; and the positivist tradition continued through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when, until quite recently, its dominance seemed assured. Likewise, several of the ideas involved in conventionalist philosophies of science have a long history, particularly in astronomy. From very early on, there developed the view that all that mattered for an astronomical theory was that it should ‘save the appearances’, that it should be a computational device which enables us to make correct and useful predictions about the observed movements of the heavenly bodies. Such theories should not be seen as describing any physical reality, or making claims to truth: their value was primarily instrumental. If more than one theory adequately ‘saved the appearances’ the choice between them should be made on the basis of partly aesthetic criteria, such as mathematical elegance.1

These different conceptions of science have also been related to more general philosophical positions and movements. In the twentieth century, these relationships are particularly interesting. Until about twenty years ago, the dominance of positivist philosophy of science was closely associated with the dominance of the logical positivist movement, itself a complex blending of the Humean empiricist tradition with the late nineteenth-century development of mathematical logic. The recent attacks on positivist philosophy of science, which have taken both realist and conventionalist forms, have themselves been linked with some of the philosophical movements that emerged in opposition to logical positivism. Thus, several conventionalist philosophers of science have been influenced by the later writings of Wittgenstein, and realist philosophy of science has partly been developed from the standpoint of ‘scientific realism’, a position which is opposed both to logical positivism, and also to the movement of analytical philosophy inspired by Wittgenstein, Ryle and Austin.2

It should already be clear that our own use of the term ‘positivism’ is a more restricted one than is usual, particularly in debates about the methodological unity of the natural and social sciences. First, the term is frequently used in such a way that the positions which we distinguish as positivist and realist are conflated under the terms ‘positivist’, or ‘empiricist’. Although positivism and realism have common features, and have both been developed within a broadly empiricist philosophical tradition, the failure to distinguish the two positions is misleading. Indeed, the differences between these positions itself reflects important divergences within the empiricist tradition, several of which are manifested in the differences between Hume and Locke. Second, ‘positivism’ is sometimes used as if synonymous with ‘naturalism’, a use which we have already criticized. Third, the term is also applied to a more general intellectual tradition which, although partly constituted by what we have called positivist philosophy of science, also involves other, more sweeping claims. In particular, positivists in this wider sense not only adopt a certain view of the natural sciences, but insist that science, conceived in this way, is the only legitimate form of human knowledge. Other intellectual enquiries must either conform to this model of knowledge, or be dismissed as providing no real knowledge at all. Questions of values, theology and metaphysics are to be rejected in this manner, and the embryonic social sciences must, to deserve the name of ‘science’, be developed on the lines of the natural sciences.

But positivism purely as a philosophy of science may be maintained without these additional claims. Thus some philosophers have adopted this view of science, without thereby rejecting other forms of knowledge as meaningless or unintelligible. Instead, they may merely wish to distinguish science from, for example, theology, sometimes even to protect theology from the claims of science, rather than using science as a weapon against theology. Similarly, though positivist philosophers of science deny the relevance of values to the conduct of science and the validity of its results, this denial need not be based upon the rejection of value claims in toto: they may simply be regarded as having no legitimate part in science.3

Our procedure in these three chapters will be as follows. In chapter 1, we examine the positivist view of science, beginning with its analysis of explanation. We then consider its general view of scientific theories, and their relation to observations. An important aspect of this view is its use of a distinction between theoretical and observational terms; this we examine separately. And in the final section, some further characteristics of positivist philosophy of science as a whole are considered, especially those associated with its concept of ‘the logic of science’.

Throughout chapter 1, although we emphasize the difficulties and problems that are raised by various positivist doctrines, we do not attempt any systematic criticism of the position. But in chapter 2, we present the realist view of science both as an alternative to positivism, and in terms of its critical diagnosis of the problems facing positivism. Thus in the first three sections, we partly parallel the corresponding sections of chapter 1, by discussing the realist accounts of explanation, theories, and the distinction between theoretical and observational terms. We conclude by pointing to some of the problems for a realist philosophy of science, and drawing out some of the characteristics common to both positivism and realism.

The organization of chapter 3 is rather different from that of the first two chapters. Only in the final section do we consider conventionalism as a general position in the philosophy of science, and even here we emphasize the diversity of positions that may be grouped under this single category. In the earlier sections of the chapter, we confine ourselves to a critical analysis of several writers and arguments which stand in opposition to both positivism and realism.

Finally, the accounts we provide of both positivism and realism are composite constructions, and although there may be philosophers of science who subscribe to every element of one of these, this is not assumed by the procedure we have adopted. Thus, we do not claim that any writer who supports, say, the positivist view of explanation, will necessarily support all the other doctrines we describe as positivist—though support for at least some of them is likely. The various elements of the realist and positivist positions do fit together into coherent, alternative conceptions of science, most fully developed in the twentieth century, but present at many earlier stages in the history of science and philosophy.4

1

Positivist philosophy of science

1 The positivist view of explanation

That the explanation of an event consists basically in showing that it is an instance of a well-supported regularity has long been maintained by positivist philosophers of science. By examining the detailed development of this view by twentieth-century positivists, we will also gain insight into the main difference between these more recent writers, and their predecessors. This consists in the considerable reliance of the former upon the techniques and concepts of modern formal logic. These have been used both to express characteristically positivist views of science with a far greater degree of rigour and precision than was previously possible, and to provide a basic framework in which to analyse the nature of scientific theories.1 There can be little doubt that the attendant rigour and precision have often been highly beneficial to the philosophy of science—though not always to the positivists, since the careful and systematic statement of their views has frequently revealed serious problems and difficulties which may be unresolvable within the positivist framework.

We will examine the positivist view of explanation in the form in which it has been presented and defended by Carl Hempel, since his account is, in several senses, exemplary.2 Let us begin with the following passage (1965a, p. 246), in which he describes a typical case of scientific explanation, and presents an analysis of it which indicates his general conception of such explanations:

A mercury thermometer is rapidly immersed in hot water; there occurs a temporary drop of the mercury column, which is then followed by a swift rise. How is this phenomenon to be explained? The increase in temperature affects at first only the glass tube of the thermometer; it expands and thus provides a larger space for the mercury inside, whose surface therefore drops. As soon as by heat conduction the rise in temperature reaches the mercury, however, the latter expands, and as its coefficient of expansion is considerably larger than that of glass, a rise of the mercury level results.—This account consists of statements of two kinds. Those of the first kind indicate certain conditions which are realized prior to, or at the same time as, the phenomenon to be explained; we shall refer to them briefly as antecedent conditions. In our illustration, the antecedent conditions include, among others, the fact that the thermometer consists of a glass tube which is partly filled with mercury, and that it is immersed into hot water. The statements of the second kind express certain general laws; in our case, these include the laws of the thermic expansion of mercury and of glass, and a statement about the small thermic conductivity of glass. The two sets of statements, if adequately and completely formulated, explain the phenomenon under consideration: they entail the consequence that the mercury will first drop, then rise. Thus, the event under discussion is explained by subsuming it under general laws, i.e. by showing that it occurred in accordance with those laws, in virtue of the realization of certain specified antecedent conditions.

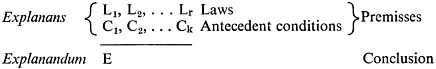

Here, scientific explanation is presented as a form of logical argument. The conclusion of the argument is a statement describing the event which is to be explained—in this case, the behaviour of a mercury thermometer which is immersed in hot water. This statement is termed ‘the explanandum-statement’. The premisses of the argument are of two kinds: statements of general laws, and statements of antecedent conditions. These are termed ‘the explanans-statements’. Thus, schematically:

So far, we have talked of the ‘general conception of explanation’ presented by Hempel. But this phrase needs to be made more precise, and qualified in various ways, before we proceed to a further examination of his account. Hempel sees his task as that of providing the necessary and sufficient conditions for something to be properly regarded as a scientific explanation. That is, he wishes to specify certain conditions to which any scientific explanation must conform, and which are such that, if these conditions are satisfied, a legitimate explanation has been given. Such specifications are often termed a ‘model’ of scientific explanation. Hempel in fact offers more than one model, and these differ in some respects, whilst having several features in common. We can regard these as attempting to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for several, slightly different, types of scientific explanation.

The two most important models, for our purposes, are called ‘Deductive-Nomological’, and ‘Inductive-Statistical’. We shall refer to these as the ‘D-N’ and ‘I-S’ models, respectively. It is the former which we described in our initial discussion of Hempel. In the latter, the law-statements of the D-N model are replaced by probabilistic, or statist...

Table of contents

- International Library of Sociology

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- part one Conceptions of science

- part two Conceptions of science in social theory

- part three Meaning and ideology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index