- 616 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geological Explorations in Central Borneo (1893-94)

About this book

This book, first published in 1902, is the product of the detailed geological survey undertaken by the Borneo Expedition of the late nineteenth century. The scientific exploration focused on Central Borneo, especially the sources of the Kapoewas and its tributaries, and its analysis of the geology of the region still today forms the bedrock of research into the area.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geological Explorations in Central Borneo (1893-94) by G.A.F. Molengraaff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I.

THE RIVER KAPOEWAS BELOW SĔMITAU.

The name of “Mudland” by which Borneo and especially West-Borneo is known, has little in it to attract the geologist, but so far. I had not been able to judge for myself whether it deserved to be so called. As, however, on the 8th of February 1894, we approached the mouth of the Kapoewas, I realized whence the name must have originated. Mud greets the newcomer far out into the sea. At a distance of 50 kilometres from the land, the clear seawater becomes discoloured by the mud carried out by the Kapoewas, and only very slowly and gradually it mixes with the salt water. The line which separates the salt from the fresh water is very clearly marked, there is a slight ripple on the water and an accumulated mass of vegetable matter and scum. When the water level is high in the rivers, which for the Kapoewas is usually during the months of November, December and January, this line of demarcation extends out as far as Poelau1) Datoe, fully 62 kilometres beyond the mouth of the Kapoewas Kĕtjil.

The real coastline had not yet come into view, but looking north I could see the hills of the Chinese districts, like an archipelago of rocky islands, rising out of the morning mist. Right in front of us was the Goenoeng2) Lontjek (124 metres), the most westerly outpost of the hills east of the marshy delta of the Kapoewas, forming a capital landmark. Southeastward, well within the delta, rises the Ambawang (450 metres) an isolated mountain surrounded by flat marshland, once no doubt surrounded by the sea, before the alluvial deposits of the Kapoewas had annexed it.

We were now fast approaching the reputed bar1), which is said to be most dangerous to cross at about 4 kilometres from the shore, because of the sandiness of the bottom there. Further out the bar is higher, but consists entirely of mud. A boat of small size can work its way through the mud even if the depth of water is a foot or two short of the draught of the vessel, but when the mud is sandy this becomes impossible. As we entered, there were 9 feet of water on the bar, so we could glide over it without much difficulty. When the bar is passed, the bed of the river becomes very deep, and ships of any size might pass over it. From its mouth up to the town of Pontianak the Kapoewas Kĕtjil1) flows on smoothly between banks covered with nipah palms, and here and there along the shore may be seen the apparently floating houses of the Malay fishermen. At Batoe2) Lajang, the monotony of this ever verdant scenery is somewhat relieved by the narrowing of the stream and the appearance of a small island. On the right side several masses of rock stand out of the water, and the only navigable channel is on the left side of the stream.

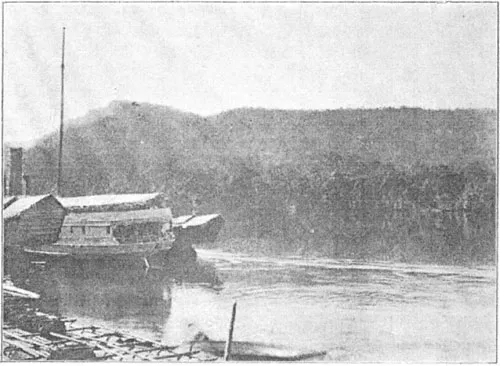

Fig. 1. THE KAPOEWAS NEAR MOUNT KĔRAMAT.

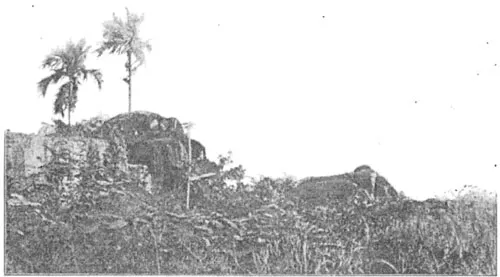

A little higher up, the river curves slightly to the southeast, and the beautiful picture of the Malay portion of Pontianak unfolds itself. The Sultan’s residence, the missigit3) and the greater part of the Malay Kampong4) are situated on the tongue of land at the confluence of the Kapoewas and the Landak. The remainder of Malay Pontianak is on the right shore of the combined rivers. On this same shore a few small sailing-vessels and bandongs5), lie at anchor. Presently the landing-place of the European portion of Pontianak comes in view, and behind it, a little further upstream and on the same shore, a dense mass of bandongs, some moored to the bank, others lying at anchor in the river secured by long rattan ropes, a sure sign that the Chinese passir6) is there. At 8 o’clock we reached the landing-place and after a few formalities I went to the badly managed hotel, close by. That same day I took a sampan1) and rowed up to the Batoe Lajang already mentioned. It is a small hill about 7 metres high composed of coarse amphibole-biotite-granite, large boulders of which lie on the surface, (see fig. 2). This granite hill partly forms the foundation of a decayed Malay fortress, where still a few cannons remain in position. Downstream, close to Batoe Lajang, are a missigit and the graves of the sultans of Pontianak. The granite rock slightly extends into the river and stretches across to the other side as a submerged bank which forms a small island close to the right shore. I was told that on the left bank rocks of the same granite may be found, evidently the continuation of the hill in that direction. I did not visit the place because a strong westwind blowing straight from the sea, the precursor of heavy rain, ruffled the water to such an extent that it was not safe to venture any further in our small sampan. So we returned to Pontianak with the greatest possible speed.

Fig. 2. BATOE LAJANG.

Pontianak itself lies low, and the ground is swampy. At high tide it becomes flooded daily, where not artificially protected, where-as at low tide the river leaves an unsightly mass of mud behind. To these tidal occurrences the drainage of the town is intrusted.

As Pontianak had no charms for me, I took the first opportunity which presented itself to go further upstream. I left on February 10th at half past eight in the morning in the Ban Tik, a small Chinese boat which had to pull up three bandongs. The Kapoewas Kĕtjil is at first fairly thickly set with houses on either side, but after the kampong Rasan is past there is a decided falling off in their numbers. The shores reveal a terrace vegetation with brushwood from 3 to 4 metres high bordering the river and behind this the real forest appears, with trees ranging from 20 to 30 metres in height. The shores of the Kapoewas are so monotonous that I got tired of them before the first day was over; this was my first experience of one of the darkest sides of travel in Borneo, viz: the oppressive, leaden monotony of its rivers. Soeka Lanting is a beautiful spot; here the river divides into two branches, the Poengoer Bĕsar and the Kapoewas Kĕtjil. I was delighted to find the river at this point opening out into a large clear sheet of water a kilometer in width.

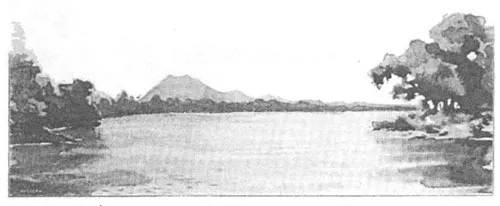

Fig. 3. MOUNT BĔLOENCAI.

Shortly after passing Soeka Lanting, the Kapoewas divides into several branches, which meet again soon afterwards and enclose small islands in their embrace.

We spent the night on the deck of our vessel and drifted past Djamboe Island, but we got so entangled in the bushes which skirt the banks that in the morning we found ourselves not much beyond that place. At some little, distance a few solitary mountains rise in bold relief from the low lying land; the most striking are Mount Bĕloengai (770 metres) (fig. 3) E. N. E. and Mount Kĕdikit (429 metres) (fig. 4) E. to S. On the south-side of Djamboe Island another branch of the river tends southward, and by afternoon I reached the upper part of the delta, above Sĕparoh Island, and then saw the entire width of the Kapoewas river before me. Straight in front the prospect was cut off by Mount Sĕbajan and other hill-tops of the ranges situated between the Lower Tajan, and the Landak river. At Tjempĕde Island near the mouth of the river of that name the characteristic sharply pointed cone of Mount Tijoeng Kandang (887 metres) (fig. 5) first comes in view. This mountain is held sacred in the neighbourhood, and the Dyaks moreover believe it to be the abode of the departed; its summit can be reached in two days from Tajan. On the first day one travels as far as Batang Tarang and the second suffices for the ascent. We reached Beloengai Island at 4 p. m. The river is here at its widest, being from 1400 to 1600 metres in width. At 6 p.m. I landed on the island Tajan, close to the house of the controller1) Westenenk, who shortly after welcomed me most heartily. His house stands on the highest extremity of the island, and the fast fading daylight only just enabled me to enjoy for a few moments the glorious view of the majestic stream, from the spot where a neat block of masonry indicates the position of the astronomical station Tajan1).

Fig. 4. MOUNT KĔDIKIT, SEEN FROM THE KAPOEWAS NEAR DJAMBOE ISLAND.

Fig. 5. MOUNT TIJOENG KANDANG, SEEN FROM THE KAPOEWAS NEAR TJĔMPEDE.

In the evening the controller and myself made our plans for the next two days at my disposal, before the Kwantan2) would be ready to take me on to Sintang. We decided to make an excursion in the hilly district in the vicinity of the kampong Tĕbang.

At sunrise next morning I went about 3/4 kilometre downstream to examine some granite blocks exposed on the right-shore of the Kapoewas. These blocks are not boulders, but form the outcrop of a granite boss, the rock is in many places much weathered and altered into yellowish brown laterite. One of these rocks, the batoe bĕlang3) or “spotted rock”, is held in great awe by the natives. It is almost black with a coating of lichens but in some places the lighter weathered surface of the granite may be seen. The undecomposed rock both here and lower down the stream is a light coloured amphibole-biotite-granite.

At 8.43 a. m. we left Tajan, in a long open sampan, here called sampan djaloer, to go up the river Tajan. The Malay kampong is built on the two shores close to where the river joins the Kapoewas. The Chinese settlement is on the island Tajan which is Government property.

Along the shores of the Tajan, a number of ladangs1) have been laid out, and all the wood is cleared with the exception of some tall rĕnggas-trees. This tree has a very stout white trunk, and the bark, which is always pealing off, hangs down in long red scaly festoons. The rĕnggas is feared both by Malays and Dyaks, because of the acrid milky juice which oozes from the bark when the tree is felled, and they therefore, generally, leave it untouched.

A long pintas2), here called bĕntassan, considerably shortened our passage upstream, and we entered a r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface To The First Dutch Edition

- Preface To The English Edition

- Introduction

- List Of The Maps, Plates And Text-Illustrations

- Chapter I. The River Kapoewas below Sĕmitau

- Chapter II. Sĕmitau and Neighbourhood

- Chapter III. Mount Kĕnĕpai

- Chapter IV. The Mandai River and the Müllek-mountains

- Chapter V. The Lake-district

- Chapter VI. Mount Sĕtoengoel, Sintang, and Mount Kĕlam

- Chapter VII. The Embaloeh River

- Chapter VIII. The Upper Kapoewas, the Boengan, the Boelit, and the boundary mountains between West and East Borneo

- Chapter IX. The Sĕbĕroewang and the Embahoe

- Chapter X. Right across Dutch Borneo from North to South

- Chapter XI. Geological description of the section across Dutch Borneo, from North to South

- Chapter XII. Summary of the geology of a portion of Central Borneo to the east of the meridian of Sintang

- Chapter XIII. Remarks on the Kapoewas and some other rivers of Borneo

- Chapter XIV. About Karangans and Pintas

- Alphabetical List Of Literature Quoted

- Register

- Appendix I: Dr. George J. Hinde. Description of Fossil Radiolaria from the Rocks of Central Borneo, Obtained by Prof. Dr. G. A. F. Molengraaff in the Dutch Exploring Expedition of 1893—94. With Four Plates

- Appendix II: Note on the Microscopic Structure of Some Limestones from Central Borneo

- Explanation of Plates

- Index