- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The principle objective of this book is to review the biological characteristics of estuaries. The volume has been as a text for undergraduates and graduate students as well as reference for scientists conducting research on estuarine systems. And the rapid development of estuarine ecology as a field of scientific inquiry reflects a growing awareness of the immense societal importance of a coastal ecosystem. While the volume of literature on estuaries amassed, scientists deemed it necessary to synthesize the field periodically. Consiquently, several books have been produced in recent years which examine variuous aspects of the disicpline.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ecology of Estuaries by Michael J. Kennish in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Alternative & Complementary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

CLASSIFICATION OF ESTUARIES

I. Introduction

The objective of this chapter is to define the basic characteristics of estuaries and to provide a review of the major schemes for classifying them. Knowledge of estuarine processes has increased substantially in recent years in response to man’s intensive use of these complex coastal ecosystems. Population centers, which developed along coastal regions, have placed an enormous demand on estuaries, utilizing this unique environment for food production, transportation, waste disposal, recreation, and other purposes. The growing awareness of the societal importance of estuaries, as well as concern over potential anthropogenic impacts, have prompted an expansion of estuarine research during the past two decades.

Concomitant with the collection of vast amounts of data on estuaries has been an effort to synthesize and summarize information for comprehension, planning, and management purposes. This effort has culminated in the classification of estuaries. The schemes of classification proposed in the scientific literature are diverse, with the bases of classification including biological, chemical, geological, and physical factors. Despite the wide range of estuarine classifications, all have proven to be useful in understanding the general processes and properties of these critical ecosystems.

II. Definition of an Estuary

The word “estuary” is derived from the Latin aestuarium, meaning tidal inlet of the sea. Aestuarium, in turn, is derived from the term aestus meaning tide. According to Webster’s dictionary,1 an estuary is defined as “a water passage where the tide meets a river current: an arm of the sea at the lower end of a river.”

Some geomorphologists and physical geographers define an estuary by the upper limit of tidal action.1a These scientists have accepted the definition of an estuary as proposed by Dionne2 which states: “An estuary is an inlet of the sea reaching into a river valley as far as the upper limit of tidal rise, usually being divisible into three sectors: (a) a marine or lower estuary, in free connection with the open sea; (b) a middle estuary, subject to strong salt- and freshwater mixing; and (c) an upper or fluvial estuary, characterized by freshwater but subject to daily tidal action.” Because of the flux of river discharge, the spatial limits of these three sectors generally vary.

Many other definitions of an estuary, which reflect the professional expertise (i.e., geomorphology, hydrology, etc.) of the writers, have been proposed in the scientific literature.3,4 Perhaps the most widely adapted definition is that of Pritchard:5 “...an estuary is a semi-enclosed coastal body of water which has a free connection with the open sea and within which seawater is measurably diluted with freshwater derived from land drainage.” This definition, however, excludes coastal lagoons which may be temporarily cut off from the sea and inundated with seawater at irregular intervals. It also excludes hypersaline coastal bodies of water in which evaporation exceeds freshwater inflow. Day,4,6 therefore, has defined an estuary as “a partially enclosed coastal body of water which is either permanently or periodically open to the sea and within which there is a measurable variation of salinity due to the mixture of seawater with freshwater derived from land drainage.” As noted by Biggs,7 the upper limit of an estuary lies in an area where chlorinity values decrease below 0.01 ‰ and the ratios of the major dissolved ions differ markedly from those in seawater.

Estuaries are transition zones or ecotones where freshwater from land drainage mixes with seawater. Most of them are drowned lower reaches of river systems, being highly variable in form and extent.8 However, coastal bays, inlets, gulfs, sounds, and embayments behind barrier islands, in which the mixing of freshwater and seawater takes place, are also considered by most workers to be estuaries. Estuaries comprise a substantial percentage of the coastline of the U.S. Approximately 80 to 90% of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and 10 to 20% of the Pacific coast consist of estuaries and lagoons,9 with estuaries occupying about 1.09 × 107 ha. Nearly 900 individual estuaries are identifiable on the coasts of the U.S.7

The Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S. are characterized by estuaries that differ structurally from those on the Pacific coast. Having formed on gently sloping coasts with broad continental shelves under the influence of a gradually rising sea level, estuaries along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts are generally extensive and often bordered by well-developed salt marshes. In contrast to these coastal plain landforms, estuaries along the Pacific coast, which are more greatly affected by tectonic activity, occur in narrow river mouths on areally restricted, continental shelves. Here, rivers drain onto steep continental slopes in many areas, and salt marshes are generally small or absent.

III. Classification of Estuaries

Estuaries have been classified according to a number of schemes. Included among the most common classifications are those based on: (1) geomorphology and physiography, (2) hydrography (water circulation, mixing processes, and stratification), (3) tidal and salinity characteristics, (4) sedimentation, and (5) ecosystem energetics. Although the literature contains numerous classification schemes for estuarine types, with the exception of the work of Fairbridge,1 the classifications have not been organized systematically.

A. Classification Based on Geomorphology and Physiography

1. Classification Based on Geomorphology

Pritchard5 classified estuaries according to their geomorphology, identifying four types (drowned river valleys; lagoon-type, bar-built estuaries; fjord-type estuaries; and tectonically produced estuaries). The general characteristics of these estuarine types are described below.

a. Drowned River Valleys

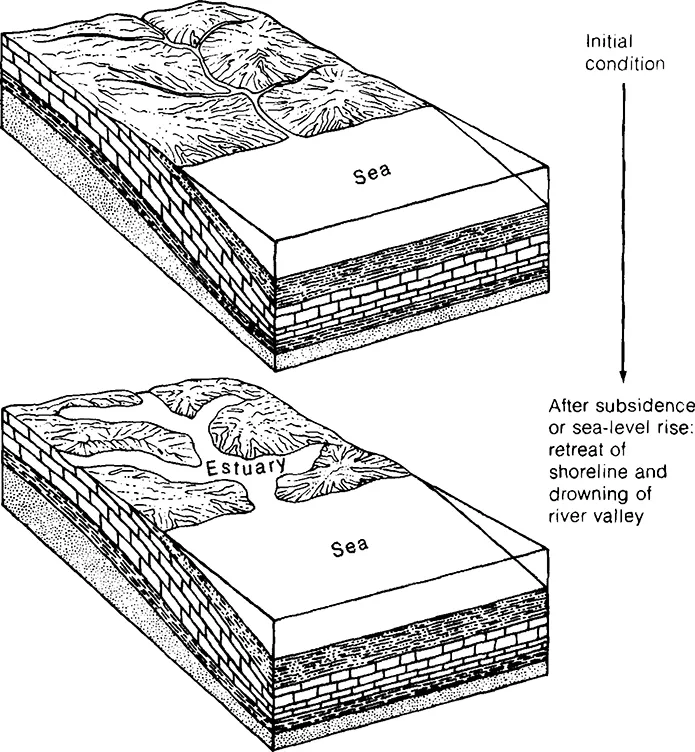

Drowned river valleys, also known as coastal plain estuaries or rias, are common features of the temperate waters of the Atlantic coast of the U.S., but can be found throughout the world. They formed within the last 15,000 years during the Flandrian transgression — a transgression which ended approximately 5000 years ago. A eustatic rise in sea level of 100 to 130 m subsequent to the Wisconsin glaciation flooded river valleys, creating these estuarine systems; they attained their present configuration during the last 2000 to 5000 years as the eustatic rise in sea level declined (see Chapter 2). The general subsidence of coastal regions, such as the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S., also contributed to their development (Figure 1). Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the U.S., are good examples of drowned river valleys (Figure 2).11 Both are large with broad expanses of water in which salinity decreases from approximately 35‰ at their mouth to less than 0.5‰ at their head.

Well-developed, drowned river valleys exist on submerged shorelines where sedimentation has not kept pace with inundation. Their width to depth ratio is usually large, and they often appear wedge-shaped, broadening and deepening seaward.12 Water depths rarely exceed 30 m. This type of estuary commonly forms on coastlines with low, wide coastal plains. Pritchard5 notes that drowned river valleys are generally confined to this geological regime.

b. Lagoon-Type, Bar-Built Estuaries

These shallow basins are semiisolated from coastal oceanic waters by barrier beaches (barrier islands and barrier spits) composed primarily of sand. Barrier beaches, enclosing lagoons and estuaries, occupy approximately 10 to 15% of the world’s coastlines.13,14 Lagoon-type, bar-built estuaries characteristically develop on gently sloping coastal plains located along tectonically stable, trailing edges of continents and along marginal sea coasts,15 and are particularly extensive on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the U.S. in areas of active coastal deposition of sediments. They appear to be restricted to shorelines where tidal ranges are less than 4 m. Notable lagoon-type, bar-built estuaries include Barnegat Bay, N.J., Pamlico Sound at Cape Hatteras, N.C., and the Laguna Madre, Tex. (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Drowned river valleys or coastal plain estuaries formed by eustatic rise in sea level or general subsidence of coastal regions. (From Earth, by F. Press, and R. Siever, W. H. Freeman and Co., Copyright © 1986. With permission.)

Lagoon-type, bar-built estuaries may have a composite origin. Rivers entering these systems from mainland regions frequently have been drowned at their lower end by a gradual rise in sea level. Formation of barrier beaches partially encloses the outer embayment, creating a lagoon-type environment,5 with narrow inlets breaching the barrier beaches and enabling the communication of estuarine and nearshore ocean waters via tidal currents.

Barrier beaches that enclose lagoon-type, bar-built estuaries can have multiple origins. Schwartz,16 Swift,17 Field and Duane,18 Godfrey,19 and Barnes20 have reviewed various hypotheses of barrier beach genesis. Four major hypotheses describe the development of barrier be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- The Author

- Dedication

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Classification of Estuaries

- Chapter 2. Origin and Longevity of Estuaries

- Chapter 3. Physical Factors

- Chapter 4. Chemical Factors

- Chapter 5. Organic Matter

- Chapter 6. Sediments

- Index