- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Target Sites of Fungicide Action

About this book

Target Sites of Fungicide Action presents a critical examination of the mode of action of antifungal inhibitors, especially the mechanistical aspects of agricultural fungicides and antifungal drugs. It provides an interdisciplinary approach through its discussions of inhibitors with target sites in sterol biosynthesis, molecular studies in fungicide research, and fungal resistance. Researchers and students in plant pathology, mycology, and medicine will find this book to be a comprehensive summary of current knowledge, as well as a source of stimulation for future research in the field of applied mycology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Target Sites of Fungicide Action by Wolfram Koeller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

TARGET SITES OF CARBOXAMIDES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. | Introduction | ||

II. | Mechanism of Antifungal Activity | ||

III. | Mutation Modification of Carboxamide Sensitivity of Fungal SDCs | ||

IV. | Action on the SDC in Fungi, Bacteria, and Higher Plants | ||

V. | Structural Requirements for Carboxamide Inhibition of Mitochondrial Complex II Activity | ||

VI. | General Nature and Composition of Mammalian Succinate-Ubiquinone Reductase (Complex II) | ||

VII. | Inhibition Kinetics | ||

A. | Kinetics of Dye Reduction | ||

B. | Kinetics of Coenzyme Q2 Reduction | ||

VIII. | Binding Studies | ||

A. | Equilibrium Dialysis | ||

B. | Photoaffinity Labeling | ||

IX. | Comments on the Stoichiometry of Carboxanilide Binding to Complex II and Molecular Mechanisms of Inhibition | ||

X. | Direction of Future Research Studies with Carboxamides | ||

References | |||

I. INTRODUCTION

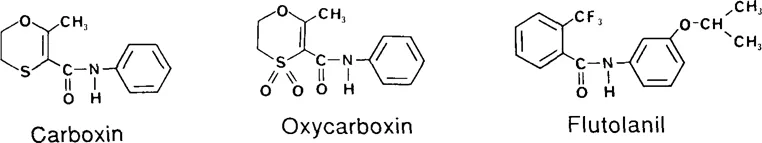

It appears that the initial carboxamide shown to be fungicidal was salicylanilide (2-hydroxybenzanilide), which was described nearly 60 years ago by Fargher et al.1 as a selective, protectant fungicide. However, it was not until 1966 that von Schmeling and Kulka reported the first truly systemic carboxamide, i.e., carboxin (5,6-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-oxathiin-3-carboxanilide) and its sulfone analogue, oxycarboxin.2 Carboxamides since then became of considerable interest for plant disease control, and subsequently an array of compounds with different planar and nonplanar ring systems were synthesized and tested for antifungal properties. Woodcock,3 and more recently Kuhn4 and Kulka and von Schmeling,5 have reviewed these heterocyclic carboxamide structures in some detail. Representative structures are shown in Figure 1.

Carboxin and oxycarboxin act as systemic fungicides for disease control displaying apoplastic movement as shown by experiments with cereals, beans, and other plants. Thus, foliage diseases can be controlled by treating the seeds or the soil with fungicide. Cytological studies have revealed the details of protective and curative effects of oxycarboxin against the bean rust fungus, Uromyces phaseoli.6,7 When bean plants were root-treated with oxycarboxin, germination of uredospores proceeded normally, but the germ tubes were shorter than those of uredospores germinating on untreated plants. Formation of appressoria and intercellular hyphae was not hindered, but no haustoria could be detected. When treatment was postponed until the chlorotic spot stage, no further symptoms developed and the original spots became less evident. Microscopic examinations showed disrupted haustoria, encased by material of plant origin. It is interesting that the mitochondria of such haustoria had become swollen with dilated cristae. Also, wall appositions were formed within the plant cell wall, indicating that plant defense mechanisms might contribute to the curative action of oxycarboxin. Hirooka et al.8 found that 3’-isopropoxy-2-trifluoromethylbenzanilide (Flutolanil) was absorbed and translocated internally through rice plants giving protectant control of sheath blight (Rhizoctonia solani) by retardation of fungal growth and penetration of infection cushions. Severely collapsed hyphae and infection cushions were observed.

Carboxamide fungicides have generally been found most active against Basidiomycete fungi, e.g., rusts, smuts, and bunts of cereals and damping off caused by R. solani.2,9, 10, 11 The 2′-phenyl analogue of carboxin (F 427) has a broader spectrum which shows preference for specific taxonomic groups of Basidiomycetes, Porosporae, and Aspergillus spp.9 It has also been noted that 2,5-dimethylfuran-3-carboxanilide is effective against some Helminthosporium and Fusarium spp.12 In vitro it has been possible, by structural modification, to extend the fungitoxic spectrum of carboxamides to include some Ascomycete and Phycomycete fungi where, for example, a number of thiophene carboxamides were active spore germination inhibitors, particularly toward Phytophthora infestans and Verticillium dahliae.13 In vivo experiments with late blight (P. infestans) on tomato plants showed that several thiophene carboxamides, e.g., 3′-n-butyl-3-methylthiophene-2-carboxanilide, gave satisfactory protectant activity.13

II. MECHANISM OF ANTIFUNGAL ACTIVITY

The first indication that carboxamides inhibit respiration was obtained in experiments with intact cells by Mathre14 and Ragsdale and Sisler.15 Glucose oxidation by R. solani mycelium in phosphate buffer was blocked to about 60% by a growth-inhibiting concentration of carboxin. With Ustilago maydis, inhibition of glucose oxidation was less severe and declined with sporidial age. However, acetate, pyruvate, and succinate oxidation was much more sensitive to carboxin than was glucose oxidation.15 When teliospores of U. nuda or mycelia of R. solani were incubated with [U-14C] glucose or [U-14C] acetate, carboxin caused a decreased incorporation of label into citrate, malate, and fumarate but an increased incorporation into succinate.14 This was the primary indication that carboxamide fungicides might affect succinate metabolism. Another early observation that carboxin affects respiration and therefore the mitochondrial electron transport system was made by Georgopoulos and Sisler.16 These workers found that carboxin selects for mutants of U. maydis which lack the alternative antimycin A-insensitive electron transport pathway.

FIGURE 1. Chemical structures of carboxamides.

Of considerable interest during these studies was the rather marked difference in carboxin sensitivity on acetate substrate as compared to glucose.15 Growth tests made with three organisms showed a tenfold increase in toxicity when acetate replaced glucose as the carbon source, and this was considered to indicate that ATP generated in glycolysis and possibly during glucose oxidation is less affected by the fungicide than is ATP formed during acetate metabolism. Yeast cells utilizing glucose anaerobically were indeed appreciably more tolerant to carboxin than those aerobically cultured on acetate. In fungi unable to grow anaerobically, growth inhibition on glucose, though less pronounced than on acetate, is quite considerable and cannot be accounted for by the small amount, if any, of inhibition of glucose oxidation by carboxin. This was explainable if carboxin inhibited some reaction in the citric acid cycle. Since glucose was not oxidized via this cycle in the presence of carboxin, it was suggested by Mathre14 and Ragsdale and Sisler15 that a lack of cycle intermediates and/or limited availability of ATP was responsible for growth inhibition.

Following studies with whole cells, the identification of the succinate dehydrogenase complex (SDC,1 complex II, succinate-ubiquinone reductase) of the respiratory electron transport system as the site of action of carboxin and related carboxamides was established by experiments with mitochondrial preparations. Succinate oxidation by mitochondria of U. maydis was very sensitive to carboxin with a Ki of 0.32 µM, while NADH oxidation was not inhibited even at a carboxin concentration of 150 µM.17 The oxidation of succinate was also inhibited in mitochondria from rat liver and pinto bean, although to a lesser extent than in mitochondria from the sensitive fungus. Particulate preparations from U. maydis and Cryptococcus laurentii, exhibiting succinate dehydrogenase activity, were also used by White18 and White and Thorn19 to study the effect of carboxin and a number of carboxin analogues. The 1,4-oxathiin carboxamides inhibited the reduction of DCIP dye by succinate and this inhibition was sufficiently high to account for both the accumulation of succinate and inhibition of cell growth. It wa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Target Sites of Carboxamides

- Chapter 2 Target Sites of Hydroxypyrimidine Fungicides

- Chapter 3 Target Sites of Tubulin-Binding Fungicides

- Chapter 4 Target Sites of Fungicides with Primary Effects on Lipid Peroxidation

- Chapter 5 Target Sites of Fungicides to Control Oomycetes

- Chapter 6 Target Sites of Melanin Biosynthesis Inhibitors

- Chapter 7 Antifungal Agents with Target Sites in Sterol Functions and Biosynthesis

- Chapter 8 Target Sites of Sterol Biosynthesis Inhibitors in Plants

- Chapter 9 Target Sites of Sterol Biosynthesis Inhibitors: Secondary Activities on Cytochrome P-450-Dependent Reactions

- Chapter 10 Target Research in the Discovery and Development of Antifungal Inhibitors

- Chapter 11 Biotechnology and Fungal Control

- Index