- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book, first published in 1986, is an excellent introduction to the main topics of economic and applied geology for undergraduate students of geology, geophysics, mining geology and civil engineering.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Economic and Applied Geology by W.G. Shackleton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

MINERAL DEPOSITS

INTRODUCTION

This chapter, together with those on coal, petroleum and groundwater, provides the background for the rest of this book. “Mineral deposits” is used here in the restrictive sense of applying to naturally formed inorganic metallic and non-metallic deposits. However, the term is often applied to any economic deposit including coal and petroleum. Texts such as Bateman (1950), Stanton (1972) and Park and MacDiarmid (1975) should be used to “flesh out” the following necessarily brief treatment of mineral deposits. References are also made to a number of papers in journals.

CLASSIFICATION OF MINERAL OCCURRENCES

Resources, Reserves and Ore

Mineral occurrences range in size from the very large aggregate we call the Earth to relatively small economically exploited mineral deposits.

The term “Resource” has been defined in many ways, generally implying something in reserve. The first part of this book is concerned with non-renewable resources such as copper, coal and petroleum. Skinner (1976, pl3) defines a mineral resource as “presently or potentially extractable concentration of naturally occurring solid, liquid or gaseous material”. Note that this is a very broad definition. McDivett and Manners (1974, p73) define a resource as “material that can be expected to become part of the reserve category during the foreseeable future through discovery or through changes in the economic, technological or political conditions”.

Reserves, with their economic implications, are the subject of considerable debate and warrant further discussion. The term “mineral deposit” must first be defined. A mineral deposit can be considered to be a volume of the Earth’s crust which contains a mineral or group of minerals in above average concentrations – that is, a positive geochemical anomaly. Traditionally, a mineral deposit from which the required material can be extracted at a profit is termed an ore deposit. However, more recent definitions are somewhat more liberal in their scope. For example, the Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy (Aus. I. M. M.) has defined ore as “a solid naturally occurring aggregate from which one or more valuable constituents may be recovered and which is of sufficient economic interest to require estimation of tonnage and grade” (Aus. I. M. M., 1981).

The same body has defined various categories of ore, given in full below:-

Proved Ore Reserves are those in which the ore has been blocked out in three dimensions by excavation or drilling, but include in addition minor extensions beyond actual openings and drill holes, where the geological factors that limit the ore body are definitely known and where the chance of failure of the ore to reach these limits is so remote not to be a factor in the practical planning of the mine operations.

Probable Ore Reserves cover extensions near at hand to proved ore where the conditions are such that ore will probably be found but where the extent and limiting conditions cannot be so precisely defined as for proved ore. Probable ore reserves may also include ore that has been cut by drill holes too widely spaced to ensure continuity.

Possible Ore (NOT RESERVES) is that for which the relation of the land to adjacent ore bodies and the geological structures warrant some presumption that ore will be found, but where the lack of exploration and development data precludes its being classed as probable.

Synonyms for the above categories are “measured”, “indicated” and “inferred”, respectively. A more recent discussion on ore reserves is given by King and Others (1982). The techniques involved in the quantitative estimation of mineral resource deposits are discussed in a later section.

The above classifications were prepared for metallic and solid non-metallic deposits but, with some modification, are also used for coal deposits. The actions of a very few unscrupulous geologists and directors of mineral exploration companies in the past several decades has led to the increased control over the issue of reports of a geological nature by stock exchange listed mining or mineral exploration companies. In Australia, for example, such reports must be compiled by a corporate member of the Aus. I. M. M. A readable account of some of the events which led to this requirement in Australia is the book “The Money Miners” (Sykes, 1978).

Traditional Classification Schemes

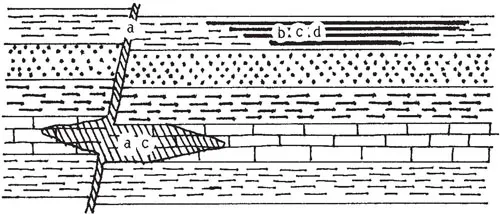

The early classification schemes of the middle nineteenth century were based on form and genesis. Later that century and to the present time most classification schemes are based mainly on genesis with some minor element of form. The initial main subdivisions of mineral deposits were primary, or bedrock, deposits and secondary, or disintegration, deposits. The terms epigenetic and syngenetic were introduced early this century. Epigenetic deposits are those which formed at a later time than that of the host rock. Syngenetic deposits formed at the same time as the host rock (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Illustrations of (a) Epigenetic, (b) Syngenetic, (c) Stratabound and (d) Stratiform Mineralisation.

Lindgren’s classification of 1911 was the first comprehensive genetic classification scheme. Variations of this scheme are still being used today (for example, Park and MacDiarmid, 1975). More recent, and traditionally, European workers, have not been satisfied with the emphasis that Lindgren’s scheme had on the importance of igneous rocks in ore genesis. Stanton (1972), for example, considers mineral deposits in terms of their associated rocks. The increasing move to an emphasis on sedimentary genesis for mineral deposits has generated considerable discussion. The terms stratabound and stratiform are being used in mineral deposit descriptions (Figure 2.1). Stratabound deposits are contained within one lithological layer (which may be sedimentary or igneous). Stratiform deposits have the form of sedimentary strata which can also be sedimentary or igneous in origin. An interesting review of these terms is in Canavan (1973).

All major texts on mineral deposits review the various classification schemes and theories of ore genesis and their development. Eateman (1958), Stanton (1972) and Park and MacDiarmid (1975) all provide interesting and informative reading on these topics.

THE FORMATION OF MINERAL DEPOSITS

Introduction

For centuries, mineral deposits were considered to be formed by exotic or extraordinary processes other than those which form the rocks of the Earth. It was not until the end of the 18th century that investigators began to seriously consider that mineral deposits may have formed in a similar manner to ordinary rocks. A consequence of this approach is that deposits could be considered to be rocks which have a chemical and/or mineralogical composition which may be of some value to our civilisation.

For example, Abraham Werner, the proponent of the Neptunist theory for the origin of rocks, considered that mineral deposits were simply special chemical sediments. This is consistent with his theory that all rocks were the result of precipitation from a primaeval ocean.

Similarly, James Hutton, leader of the Plutonist school, proposed that mineral deposits were formed by intrusion of molten sulfurous material. This is consistent with his theory that igneous rocks were formed from molten rock material.

Obviously, the above two views are extreme. However, it is significant that both workers saw the formation of mineral deposits not as particularly special events but as part of the broad scheme of rock forming processes.

Igneous Mineral Deposits

Introduction The stages in the crystallisation of a magma may be summarised:

1.Magmatic Stage – where there is equilibrium between liquid (silica melt) and crystalline phases.

2.Pegmatitic Stage – where there is equilibrium between liquid, crystalline and gas phases.

3.Pneumatolitic Stage – where there is equilibrium between crystalline and gas phases.

4.Hydrothermal Stage – where there is equilibrium between crystalline, aqueous solution and gas phases.

Note that it is not unusual to symplify the above scheme by combining 2 and 3 into the generalised pegmatitic stage.

Magmatic Deposits Mineral deposits formed during the magmatic stage are of great importance to our civilisation.

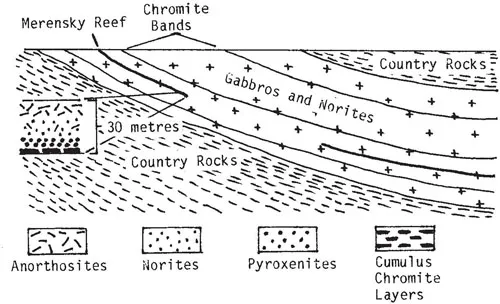

Figure 1.2: Simplified Diagram of the Bushveld Igneous Complex Showing Details of the Merensky Reef.

One example is the Merensky Reef, part of the Bushveld Complex in the Transvaal of Africa. This complex is 460 by 240 kilometres in areal extent, 8000 metres thick and has a lopolithic form. Successive intrusions of granodiorites, diorites, gabbros and ultramafic magmas were differentiated by gravity settling. During this process early crystallising chromite settled ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Introduction

- 1. Mineral Deposits

- 2. Coal

- 3. Petroleum

- 4. Groundwater

- 5. Resource Exploration

- 6. Exploration Geophysics

- 7. Exploration Geochemistry

- 8. Drilling Techniques

- 9. Bore Hole Logging

- 10. Extraction Techniques

- 11. Mineral Processing

- 12. Engineering Geology

- 13. Environmental Geology

- 14. Geology, Economics and Politics

- Index