- 72 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Constructed Wetlands: Hydraulic Design provides fundamental information on internal wetland hydraulic and biochemical processes, as well as practical guidance on the effective design of wetlands for water treatment. It includes the latest innovations and technological advances of constructed wetlands based on the newest technologies in the field.

Features:

-

- Explains how various pollutants are either retained or removed from treatment systems

-

- Examines system geometry, flow rate, inlet-outlet configurations, and more

-

- Offers useful guidance and tools to practitioners for designing wastewater treatment structures naturally and optimally

-

- Introduces the various aspects of hydraulic engineering through porous media

This book will serve as a valuable resource for practicing professionals, researchers, policy makers, and students seeking to gain an in-depth understanding of the hydraulic processes involved in constructed wetlands water treatment systems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Constructed Wetlands by Saeid Eslamian,Saeid Okhravi,Faezeh Eslamian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to Constructed Wetlands

Saeid Eslamian, Saeid Okhravi, and Mark E. Grismer

1.1 GENERAL

In this fast-changing and highly interconnected world, problems related to water availability, scarcity, quality, and the associated conflicts are numerous, complicated, and challenging. Efforts to effectively resolve these problems require a clear vision of future water availability and demand as well as new ways of thinking, developing, and implementing water planning and management practices. Reclaiming and reusing treated wastewater can create an alternate water source for secondary use by reducing demand on potable water sources utilized for drinking water (Eslamian 2016; Eslamian et al. 2016).

Nowadays, the use of constructed wetlands (CWs) for urban stormwater and wastewater treatment is widely adopted in many urban environments, many of which are successfully incorporated into urban landscapes (Okhravi et al. 2016; Jabali et al. 2017). First, as compared to conventional energy-intensive treatment technologies (physical–chemical–biological treatments), CWs are an attractive and stable alternative due to low cost and energy savings (Zhang et al. 2009). Second, CWs can provide potentially valuable wildlife habitat in urban and suburban areas (Rousseau et al. 2008), as well as an esthetic value within the local natural environment. Finally, CWs are often beneficial in small- to medium-sized towns due to easy operation and maintenance, providing a useful complement to the traditional sewage systems used predominantly in larger cities. Thus, the introduction of CWs in municipal wastewater treatment systems has been something of a revolution. The incorporation of CWs aids in future design plans for new wastewater treatment facilities and provides a greater understanding of CW benefit for residents (Vymazal 2019). Abundant research indicates that wetlands can filter wastewater in an environmentally and economically efficient manner. With their low mechanical input and high environmental benefits, development of CWs appears to be a good tool for the water resources planners considering wastewater treatment and reuse.

Like conventional wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), CWs are engineered systems, but are much lower-cost construction, operation, and maintenance alternative for wastewater treatment and reclamation where applicable. They deploy eco-technological biological wastewater treatment technology, have an excellent pollutant removal performance, and enjoy lower energy consumption. CW systems are designed to mimic processes found in natural wetland ecosystems. Thus, CWs are an environmentally friendly technology that helps to reduce environmental impacts associated with wastewater treatment by treating waste on-site with low energy and chemical consumption (Flores et al. 2019).

CWs are shallow water bodies typically planted with water-tolerant vegetation common to the locale. The basin substrate material is usually sand or gravel that enables root penetration and sedimentation filtration and pollutant uptake processes to remove pollutants from wastewater. A CW is comprised of five primary design aspects including basin dimensions, substrate materials, type and density of vegetation, and liner and inlet/outlet configuration. Generally, wastewater enters the CW basin through a distribution manifold and flows over the surface and/or through the substrate and discharges from the basin through a structure that controls the CW water depth (Sudarsan et al. 2015).

CWs reduce contaminant concentrations through a complex of physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms that occur through water, substrate, plants, and microorganism interactions (Chang et al. 2012). Particular removal mechanisms depend on the wastewater constituents, type of substrate, and available plant/microbial species in the system. Physical procedures are mainly filtration by the substrate layer, plant-root zone, and sedimentation. The main chemical reactions consist of chemical precipitation, adsorption, cation exchange, and oxidation/reduction reactions (Ramond et al. 2012). It is widely acknowledged that biochemical reactions attributed to bacterial communities (biofilms) play the most important role in pollutant transformation in aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Chang et al. 2012; Samsó and García 2013).

Design considerations include hydrodynamic factors aimed at optimizing performance of the various physical, chemical, and biological treatment processes within the CW system. The macrophytes in CWs can support a number of very important pollutant removal mechanism, including removal of suspended solids and associated contaminants (e.g., nutrients, metals, organic contaminants, and hydrocarbons). In addition, design considerations for stormwater treatment CWs include the botanical structure and layout of the wetland and the hydrologic regime necessary to sustain the botanical structure. However, the operating conditions of these systems are stochastic, with intermittent and highly variable hydraulic and pollutant loading. The achievable treatment by a CW system can be improved by careful consideration of such factors as the CW shape, vegetation, wetland volume, and the hydrologic and hydraulic effectiveness. The relationship between residence time and pollutant removal efficiency is largely influenced by the targeted particulate settling velocity and reaction kinetics that are controlled by the CW hydraulics.

To date, previous publications on CW systems have focused on comprehending the processes leading to the pollutant removal. Research on flow hydraulics through the CW porous media (substrate) has concentrated primarily on the assessment of relationships and interactions between microbial communities and plants and the reduction of pollutants in the system (Steer et al. 2002; García et al. 2005; Caselles-Osorio et al. 2007). However, there are areas of CW internal hydraulic functioning that remain poorly understood. Comparatively, there is less research dedicated to CW hydraulic design. Thus, this book assesses and elaborates CW hydraulic design aspects to obtain the best CW hydraulic and treatment performance (Persson et al. 1999; Zahraeifard and Deng 2011; Alcocer et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014a, 2014b; Okhravi et al. 2017). Our objective with this book is to provide information about the internal hydraulic behavior of CWs as described by hydraulic parameters like hydraulic efficiency, active/dead zones distribution, and short-circuiting as related to pollutant removal efficiency.

1.2 CW CONFIGURATIONS

Wetlands can be effective in removing biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), total suspended solids (TSSs), nitrogen, and phosphorus, while also reducing the metals, organics, and pathogen content of storm- or wastewaters (Kadlec and Wallace 2008). CW design configurations are classified according to the flow pattern through the CW system, type of wastewater treated, basin substrate, dominant macrophytes, operational usage type, and desired level of treatment. Among these criteria, there are three main CW types considered in the literature based on flow patterns: free-water surface (FWS), horizontal subsurface flow (HSSF), and vertical subsurface flow (VSSF) systems (IWA 2000).

1.2.1 Free-Water Surface CWs

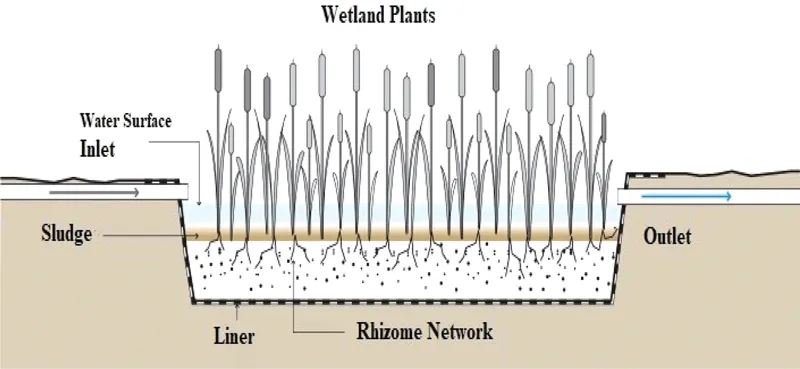

FWS CWs are defined by the exposure of the water surface to the atmosphere and shallow ponded depths (~0.3 m) where treatment is achieved largely within the water column (EPA 2000). SSF wetlands (natural and constructed) are defined by most flows below the substrate (e.g., sand/gravel) surface (Kadlec 2009). Both wetland types may contain a variety of plants including submerged, emergent, and floating plants. Many FWS wetlands have similar characteristics to natural marshes that provide additional wildlife habitat benefit (Figure 1.1).

FWS CWs tolerate variable water levels and nutrient loads and can achieve a high removal of suspended solids and BOD and moderate removal of pathogens, nutrients, and other pollutants, such as heavy metals, depending on the CW residence time and ambient temperatures. This type of wetland is more appropriate for low-strength wastewater following primary or secondary treatment sufficient to reduce wastewater BOD due to limited aeration (Vymazal 2011). FWS CWs are a good option where land is readily available and/or inexpensive, and they work well in warm climates. The hydraulic efficiency of FWS CWs depends, in part, on how well the wastewater is distributed at the CW inlet (Tilley et al. 2014). Wastewater typically flows into the CW using weirs, orifices, or a distribution manifold pipe.

1.2.2 Subsurface Flow (SSF) CWs

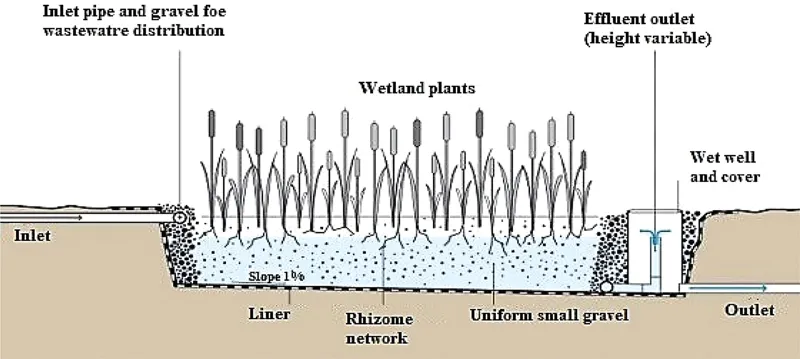

Greater wastewater treatment (at comparatively lower flow rates than in FWS CWs) is possible in SSF CWs (Vymazal 2011). These systems rely on water flow through the substrate material in a horizontal (HSSF) or vertical configuration (VSSF). HSSF CWs are typically a shallow basin (depths of 0.3–1.0 m) filled with filter material (usually sand or gravel substrate) and planted with vegetation tolerant of saturated or submerged conditions (Figure 1.2). Water levels within the SSF CW are maintained at several centimeters below the substrate surface through control of outlet conditions. Depending on the wastewater inlet–outlet conditions, the wastewater moves through a wetland substrate more-or-less horizontally. Within the wetland substrate, the wastewater encounters a network of aerobic, anoxic, and anaerobic zones associated with relative depth, plant-rooting depths, and overall CW depth. Aerobic zones occur near the substrate surface and around the plant roots and rhizomes that leak oxygen into the substrate (UN-HABITAT 2008). However, much of the saturated bed is anaerobic under most wastewater loadings. Wastewater treatment generally occurs by filtration adsorption and microbiological degradation processes. Typical plant species include common reed (Phragmites australis), cattail (Typha spp.), and bulrush (Schoenoplectus spp.). HSSF CWs can effectively remove wastewater organic pollutants (TSS,1 BOD, and COD2) as well as various nutrients, metals while breaking down some industrial or pharmaceutical chemicals.

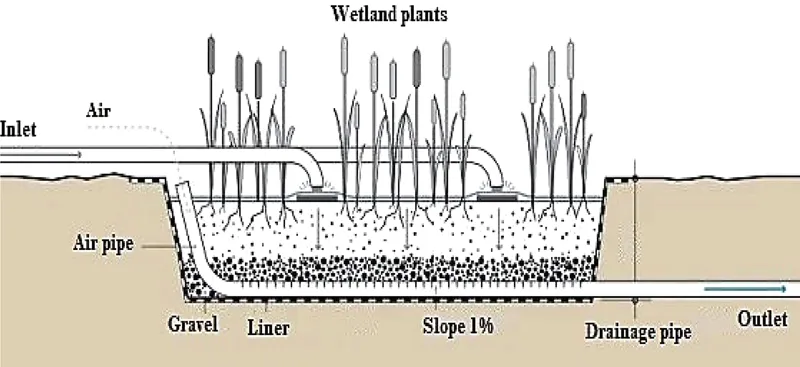

VSSF CWs are also a planted filter domain for secondary or tertiary treatment of wastewater (e.g., gray- or black-water) that enters at substrate surface, gradually percolates, and drains at the bottom (Figure 1.3). As possible with other systems, intermittent dosing (4 to 10 times a day) of the VSSF CWs enable the substrate to oscillate between aerobic and anaerobic conditions, thereby facilitating nitrification (Tilley et al. 2014). The oxygen diffusion from the air created by the intermittent dosing system contributes much more to the filtration bed oxygenation as compared to oxygen transfer through the plant (Brix 1997; UN-HABITAT 2008). However, the primary role of vegetation is to maintain permeability in the filter and provide a habitat for microorganisms. Schematic illustrations of horizontal and vertical SSF CWs are shown in Figures 1.2 and 1.3, respectively.

Generally, some type of primary wastewater treatment is essential to limit clogging within SSF CW substrate and ensure effective treatment. Depending on the situation, such a pretreatment might include septic tanks, sand or rotating screen filters, and anaerobic baffle reactors (Hoffmann and Platzer 2010). A well-designed inlet layout could improve the removal efficiency of these types of CWs by preventing short-circuiting.

By way of an example, Liu et al. (2019) investigated the removal efficiencies and accumulated concentrations of the antibiotics oxytetracycline and ciprofloxacin in three pilot-scale CWs with different flow configurations (FWS, HSSF, and VSSF). They found that the average mass removal efficiencies of the CWs for the target antibiotics in one year of treatment ranged from 85% to 99%. The VSSF achieved the greatest and most stable removal efficiencies for oxytetracycline (99% ± 0.27%) and ciprofloxacin (97% ± 0.26%). Further, their analysis indicated that the type of CW influenced the bacterial community more significantly than the wetland substrate and residual concentration of antibiotics.

1.2.3 Hybrid CWs

Greater nitrogen removal from domestic wastewater was one of the primary drivers to develop CW technology. The nitrogen degradation process includes nitrification of ammonia under aerobic conditions followed by denitrification...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Authors

- CHAPTER 1 ■ An Introduction to Constructed Wetlands

- CHAPTER 2 ■ Hydraulic Theory: Constructed Wetland

- CHAPTER 3 ■ Hydraulic Design of Constructed Wetland

- CHAPTER 4 ■ Factors Affecting Constructed Wetland Hydraulic Performance

- CHAPTER 5 ■ Future Constructed Wetland Research Orientations

- REFERENCES