- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

New Jersey. The name evokes many images, most of which are narrow stereotypes that fall short of reality. For example, though New Jersey's salient cultural characteristic is its high population density–the highest in the United States and higher than that of Britain–there is a surprising amount of open space in the state. Areas of the pinelands remain virtually unexplored, vast bogs are nearly impenetrable, and lush forests on the Appalachian ridges and holly-decked beaches on the ocean invite the city-weary urbanite. This geographic study of New Jersey, a multidimensional portrait of the state, incorporates three major themes: (1) the state's cultural diversity, an amalgam dating from colonial days, of many varied ethnic, national, and racial groups; (2) its bipolar orientation to two neighboring giant metropolitan areas, New York and Philadelphia, again a factor that dates to the time of the Revolution; and (3) an economy heavily influenced by the state's accessibility to major metropolitan centers and its well-developed corridor functions. Dr. Stansfield depicts New Jersey as a state others should watch: How it controls suburban sprawl, environmental deterioration, and the internal competition among agricultural, suburban, industrial, and recreational uses of land and water resources offers a model for the rest of the United States. Newark's Mayor Gibson observed of his city, "I don't know where America's cities are going, but I think Newark will get there first." It also might be fairly concluded, writes Dr. Stansfield, that wherever the United States is heading, New Jersey could get there first.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

FIGURE 1.1.

Chapter 1

Introduction

Some Basic Themes

New Jersey: The name evokes many images, but these commonly lack a positive focus and frequently fail to represent reality. However, the real New Jersey will become apparent to those who seek it out. Through 200 years of description of New Jersey—by geographers, journalists, historians, and social scientists as well as by astute travelers and perceptive citizens— three general themes are repeated that accurately depict the state.

The first is that New Jersey is culturally diverse—an amalgam of varied ethnic, national, and racial groups. From its colonial origins, New Jersey has had a heterogeneous culture that reflected no particular or distinctive proto-American culture and thus reflected in fact the new, definitively American culture. In many respects—geographic, economic, demographic, and historic—New Jersey is not just representative of the evolving American cultural landscape, but is perhaps the quintessence of the American experience, the American process, and the American dream.

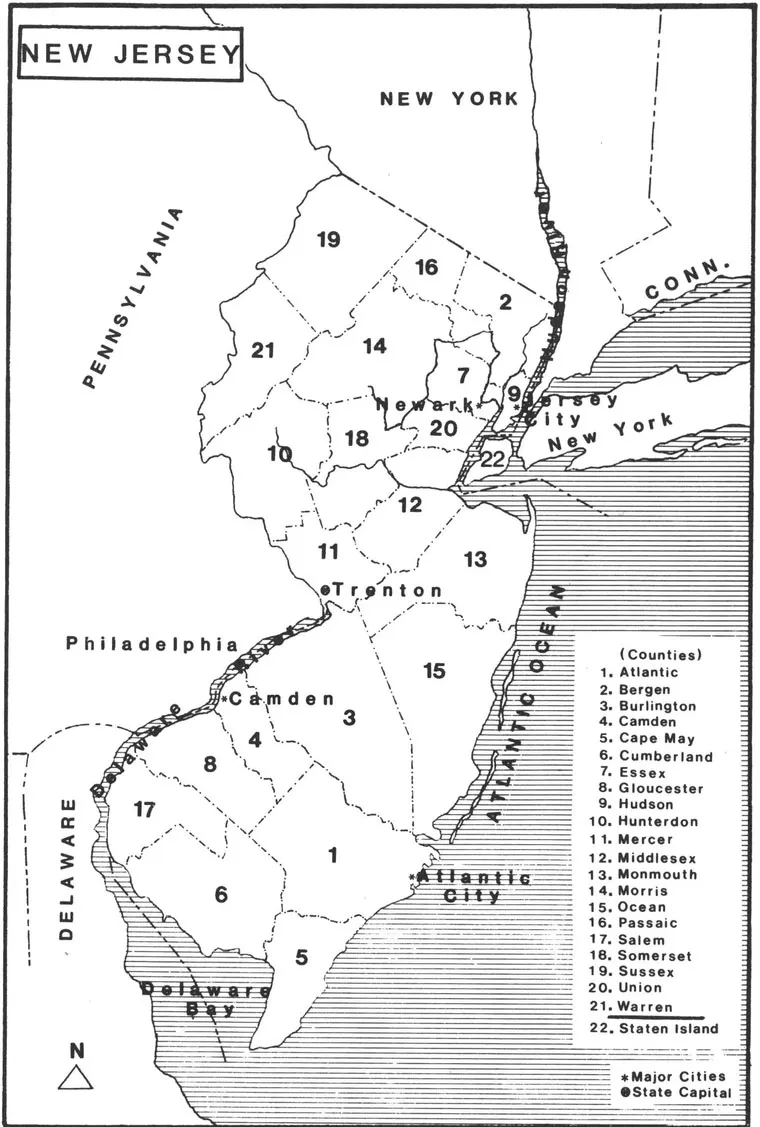

The second observation in common is that of New Jersey's bipolar orientation to its neighboring giant metropolitan centers, New York and Philadelphia (see Figure 1.1). The image of New Jersey as "a barrel tapped at both ends," attributed to Benjamin Franklin, is a widely understood one. New Jersey has somehow stopped short of developing its own cosmopolitan, powerful metropolis on the scale of its two dominant neighbors. It seemed at one time that the state was perversely doomed to play suburb: an array of satellites without a central star to call their own. In the present phase of deconcentration of many (if, indeed, not all) urban functions, New Jersey may come into its own as New York and Philadelphia effectively decentralize and disperse into New Jersey, as well as further into New York State and Pennsylvania.

An important corollary of New Jersey's intermediate position between New York and Philadelphia has been its corridor function. A prevalent image of New Jersey— that of a transportation-dominated landscape with the New Jersey Turnpike's' clamorous traffic rushing between the Newark Airport and the huge port facilities of Newark and Elizabeth—is an accurate if nearsighted view of the state. Since colonial times New Jersey has functioned as a corridor, and that function has been an important part of its economic and cultural life. Mobility and dispersal, suburbanization and exurbanization are typical of New Jersey and have been so throughout its history, just as they are prevalent themes in the contemporary United States.

A third fundamental observation about New Jersey and New Jerseyans is that the entire state's economy is heavily influenced by its accessibility to major metropolitan centers and its well-developed corridor function. The earliest geographers of the United States, for example, observed that New Jersey's agriculture produced a wide variety of crops and animal products, much of it destined for delivery as high-priced fresh produce to nearby urban markets. Likewise, New Jersey industry has been strongly influenced by the high density of transport facilities in the "corridor" and the proximity of huge markets, both industrial and consumer. The evolution of the northeastern seaboard megalopolis, that constellation of great cities growing toward one another along their interconnecting transport arteries, has enhanced the relative centrality of New Jersey. The state is midway within the southern New Hampshire-northern Virginia megalopolis, shown as the continuous bright area along the eastern coast in Figure 1.2. The heavily industrialized nature of New Jersey is thus based primarily upon its "situational resource" rather than on minerals or richly productive agricultural resources. Relative location has been, and continues to be, New Jersey's prime asset.

FIGURE 1.2. Nighttime Census Map. On viewing nighttime satellite photos showing cities as brilliant spots of light against the darker countryside, census officials realized that a satellite photo was very like a negative of the census dot-map of population distribution. This map negative highlights the continuous interlinkage of the northeastern megalopolis much as it might appear to astronauts seeing it at night. (U.S. Bureau of the Census)

Variations on the Themes

New Jerseyans—patriots, partisans, journalists, and scholars—tend to find themselves on the defensive when discussing the state. More than a century ago, a popular book included such a defense of New Jersey:

Although New Jersey, ever since her admission into the Union, has been the butt for the sarcasm and wit of those who live outside her borders, the gallant little state has much to be proud of. Her history is rich in instances of heroism, especially during the Revolutionary period. Her prosperity is far greater than that of many noisier and more excitable communities.... her territory includes every variety of scenery, from the picturesque hills and lakes of her northern regions to the broad sandwastes of her southern counties. Those interested in the statistics of industry will find much that is worthy of notice in her iron-works and other great manufacturing establishments, while those who seek the indolent delights of summer enjoyment cannot fail to be charmed with her famous and fashionable sea-side resorts. (Bryant 1874, 47)

Geographer Peter Wacker felt obliged to ask the rhetorical question as to why New Jersey should be of interest to scholars, answering with the observation that if New Jersey were an independent country of comparable population, or even another state, the question would not arise (Wacker 1975, 2). Popular historian and geographer John Cunningham observed that New Jerseyans rate the state highly as a place to live, indicating that the poor image of New Jersey is mostly generated, and swallowed, outside rather than inside the state (Cunningham 1978, 11).

This apparently poor, or at least blurred, image may be traced to the lack of a single, centralized, New Jersey-based government until near the end of the colonial period. Historically, New Jersey was not one colony but rather was referred to as "The Jerseys"; the division of East Jersey and West Jersey was remarkably close to the contemporary functional region boundary between a metropolitan New York orientation and a metropolitan Philadelphia orientation.

In addition, the lack of a distinctively "Jersey" culture is a situation not unconnected with New Jersey's role in developing and displaying the majority American culture. There is little in the state that is unexpected, unusual, or flamboyant. An obvious, though generally unremarked, corollary of this is that New Jersey's human landscape is typically American and therefore unexceptional within the national context. New Jersey shares with Pennsylvania an important role as cultural source or hearth for much of American culture.

A final and immediately relevant factor in New Jersey's notoriously unfocused image is the prevalence of externally based metropolitan news media whose writers and commentators apparently attempt to gain reputations as sophisticates by sneering at the suburbs, particularly New Jersey. New Jersey is a predominantly urban state of over 7 million people without a single commercial VHF television station based within it until 1983. (Delaware is the only other similarly deorived state.)

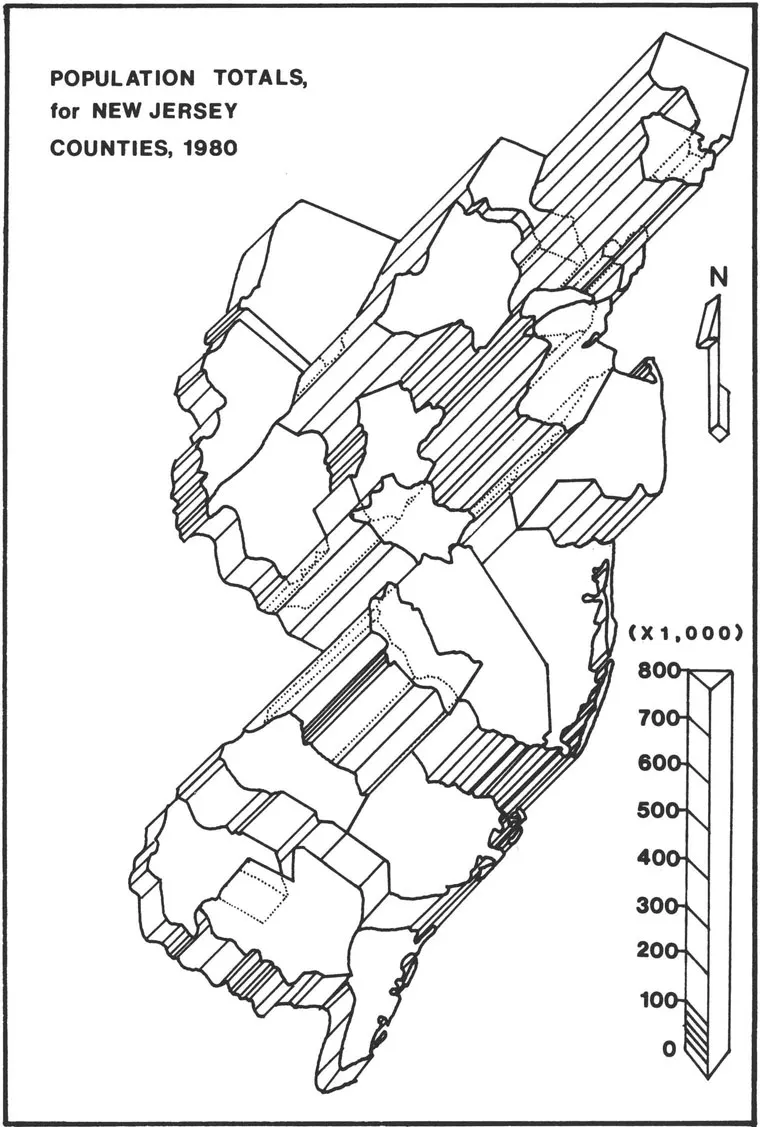

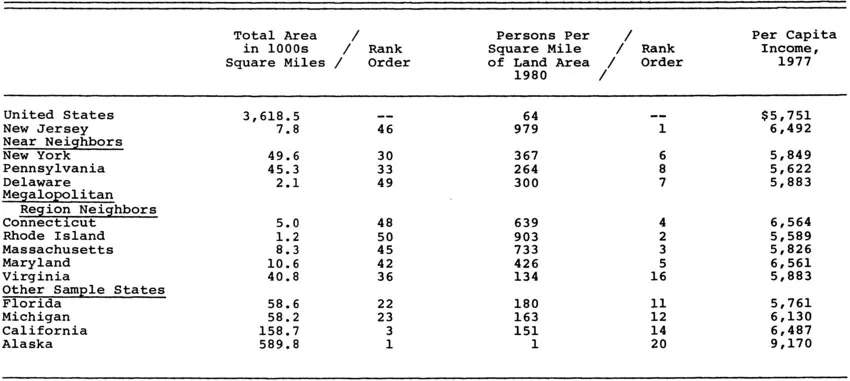

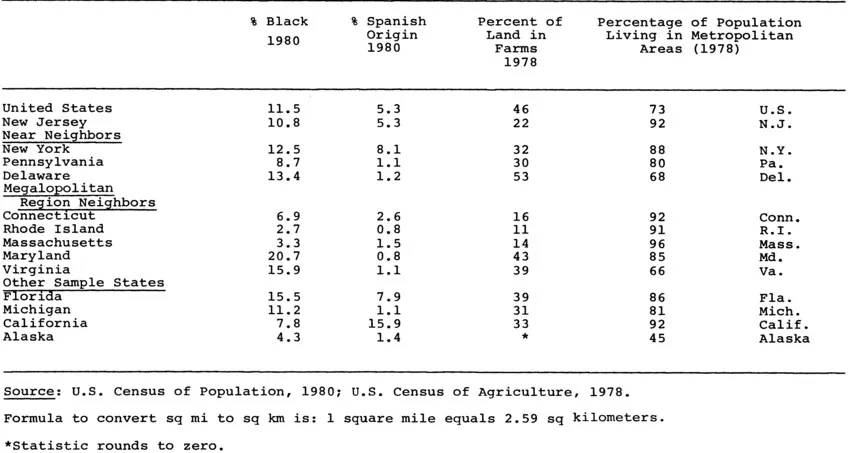

No region or area as large as a state would be expected to be homogeneous in its physical, economic, or cultural geography. Partisans of all states tend to emphasize the variety within their state and note the superlatives. New Jersey, though, seems to have more than its share of paradoxes, exceptions, and curiosities, considering that only four states (Rhode Island, Delaware, Connecticut, and Hawaii) are smaller in territory. New Jersey's salient cultural characteristic is its high population density—at 979 people per sq mi (378 per sq km), the highest in the United States (see Figure 1.3). The national average is only 64 per sq mi (24 per sq km), and few states even approach New Jersey in density (see Table 1.1). Only Massachusetts has a higher percentage of its population living in metropolitan areas, and only California and Connecticut match New Jersey's figure. New Jersey's per capita income is fifth highest in the nation, outranked only by Alaska, Connecticut, Maryland, and Nevada. New Jersey is close to average in its proportion of black population and precisely average in Spanish-origin population percentage (Table 1.1). While in some of the older industrial cities of northern New Jersey the population density approaches 40,000 per sq mi (15,440 per sq km), large tracts of the Pine Barrens are virtually

FIGURE 1.3. Population Totals, by Counties. A striking view of New Jersey's population distribution (and political geography) is this three-dimensional county outline map: the north-oriented nature of the state's population is evident.

TABLE 1.1 Representative Statistics: New Jersey in Comparison with Its Neighbors and Leading States in Statistical Categories

empty. Some Pinelands rural townships have population densities of less than 20 per sq mi (7.7 per sq km). New Jersey's population increased by only 2.7 percent from 1970 to 1980, far below the U.S. average of 11.4 percent, but respectably above those of its two largest neighbors. Pennsylvania barely grew at 0.6 percent, and New York suffered a loss of 3.8 percent (U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1980). Another paradox is that the license plates of this heavily industrial state brag "Garden State." Perhaps best known for its seashore resorts, New Jersey includes a section of the Appalachians (High Point, naturally the highest point, is 1,803 ft or 549 m high) that is also a mountain resort area. In a state known for its suburbs and industrial satellites of out-of-state big cities, Camden and Newark have attained a kind of grim notoriety among urbanists as "worst cases in the nation."

The corridor function of New Jersey means that many travelers are merely transients on their way to or from an out-of state metropolis. The very scale of the demand for transport facilities in the corridor eliminates any possibility of scenic, lightly traveled roads through bucolic countryside. "Corridor vision" may delude the corridor user into thinking that all of New Jersey must be like the congested corridor at its metropolitan extremes. In fact, New Jersey is 40 percent forested, a higher proportion in forest than is found in Minnesota or Alaska and about the same percentage as California.

"Garden State" is as much nostalgic as descriptive: a quick look through an atlas shows that "Manufacturing State" might be more appropriate. New Jersey's value added by manufacturing (value added is the difference between the value of the raw materials or components and the value of the finished or shipped manufactured product) outranks every other state with but six exceptions. Only California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania outproduce New Jersey in manufacturing, and New Jersey produces more goods by this measure than the states of Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, and Wyoming together! Considering its population size, New Jersey's economy is more dominated by manufacturing than three large states that outproduce it in total value. New Jersey's population, only 31 percent of California's, produces 44 percent of California's value added; similarly, New Jersey, with but 41 percent of New York's population, produces 52 percent of New York's value-added total. New Jersey also produces slightly more than Pennsylvania's output in relation to population.

If New Jersey were an independent nation in the world community, it would have more people than Denmark, Finland, Switzerland, Norway, Ireland, New Zealand, Bolivia, Haiti, Guatemala, Angola, or Tunisia. New Jersey's population is larger than any of ninety-five independent countries.

Related to New Jersey's highly industrialized and urbanized character is its relatively high income level. If this is expressed as an average income per capita, New Jersey as an independent country would have a higher average than that of the United States. In fact, it would be higher than every independent state in the world with the exception of some oil-rich, relatively lightly populated, Persian Gulf states (Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia—the only one of these that also exceeds New Jersey's population), Nauru (about 10,000 people on an island composed mostly of phosphate rock exported for fertilizer), and Switzerland.

For all its urban-industrial superlatives, New Jersey manages to be a frontier. It is clearly on the inner frontier where Americans are grappling with the intensifying problems of how to deal with a changing, perhaps diminishing, resource base and how to shift toward reliance on long-distance imports. It is a frontier in developing new strategies of pollution control and waste management. For much of its history, it has occupied a place on the frontiers of decentralization of urban populations and functions.

Finally, New Jersey is among the leaders in the ongoing human reassessment of the problems and potentials of the physical landscape. Kenneth Gibson, the mayor of Newark—the state's largest city and one with painfully obvious urban problems— has remarked, "I don't know where America's cities are going, but I think Newark will get there first." Geographers might as reasonably conclude that, wherever the United States is heading, New Jersey could get there first.

The "City of New Jersey"

In addition to ample evidences in the cultural landscape of New Jersey that it is a preeminently metropolitan state, statistics show that almost the entire area of the state is officially part of metropolitan systems.

Metropolitan areas have been recognized by the U.S. Bureau of the Census since the late...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 EARLY SETTLEMENT

- 3 THE PHYSICAL SETTING

- 4 THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

- 5 POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

- 6 TRANSPORTATION

- 7 AGRICULTURE

- 8 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

- 9 THE METROPOLITAN STATE

- 10 REGIONS

- 11 PLANNING

- Bibliography, Selected and Annotated

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New Jersey by Charles A. Stansfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.