- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

China As A Maritime Power

About this book

This book examines the evolution of Chinese maritime power for each of three major periods in modem Chinese history: 1945 to the Sino-Soviet break, 1960 to the Lin Biao incident, and 1971 to the present.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access China As A Maritime Power by David G. Muller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

The End of World War II Through the Sino-Soviet Break

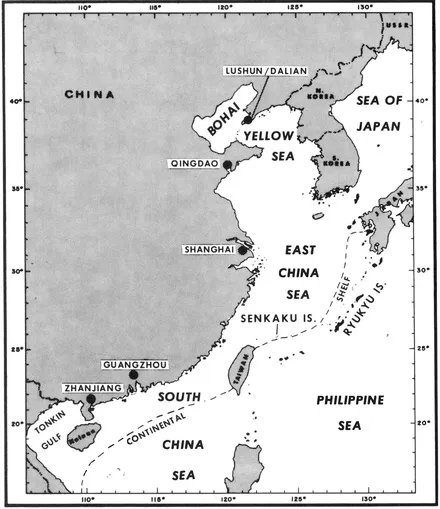

Figure 1.1. The China seas and the continental shelf

CHAPTER ONE

Naval History, 1945–1960

The Navy of the Republic of China, 1945–1949

At the end of World War II, the Republic of China (R.O.C.) had no navy. Pitifully small and underdeveloped in the 1930s, the R.O.C. Navy evaporated before the seapower of Japan and played no role in the Chinese war of resistance. The entire navy—57 small and ill-equipped ships and craft—was wiped out piecemeal. Japan occupied all of China's coastal ports and shipyards, indeed virtually the whole of China's coast, trapping both the Chinese Nationalists and Communists deep in the interior.

The war caught some 2,000 Chinese naval personnel in the United States and Great Britain, where they were undergoing training for what was to have been a major expansion of Chinese naval power.1 Five battleships and 10 cruisers were to have been the nucleus of a new Chinese fleet. In 1945, most of these officers and enlisted technicians returned to China, where they formed the promising core of a renewed program of naval development. In addition to their modern technical training, they had absorbed many of the professional values of the navies with which they had studied and thus were less prone to the complacency and corruption that plagued all branches of the Nationalist military.

The postwar Chinese Navy needed ships, of course, and these were forthcoming, chiefly from the United States. Between 1945 and 1949, China received 271 World War II surplus ships and craft from the United States.2 Britain and Canada provided another 15 ships, and an additional 33 were transferred from Japan as war reparations. The flagship of the new fleet was the 7,400-ton* ex-HMS Aurora, an impressive cruiser provided by the British in 1948 and renamed Chongqing (Chungking). Chongqing was destined to play an important role, both symbolic and concrete, in the demise of the old R.O.C. Navy and the development of the new naval force of the People's Republic of China.

With the war surplus ships came American naval advisors. The U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in China had an active naval contingent that supervised and coordinated the transfers of ships, weapons, and other equipment and trained Chinese naval personnel in their use. The training was not only technical; U.S. advisors attempted to instill in a largely uninterested and certainly inexperienced cadre of naval commanders and staff officers an awareness of how naval forces could be used in modem warfare. The Kuomintang government and military establishment, however, were almost solely interested in pursuing the developing civil war against the Communists, and the navy figured only peripherally in the government's strategy against a land-based foe. The development of the R.O.C. Navy in the latter 1940s reflected this bias. Virtually all naval operations conducted during this period were simply seaward extensions of ground operations.

The Civil War

In 1945 and 1946, the focus of most of the developing civil war was in the Northeast. In the maritime sphere, the Communists shuttled supplies and men back and forth between the Liaodong peninsula of Manchuria and their enclave on the Shandong peninsula, hemmed in by Nationalist ground forces. In its first operations since the navy had been demolished by the Japanese in 1937, the rebuilt R.O.C. Navy sought in 1946 to interdict this traffic with frequent patrols in the Bohai Strait between the two areas. By August 1947, the navy had progressed to the point that it was able to stage an unopposed amphibious landing on the south coast of Shandong, where some reinforcement of troops was needed, and in the following month the navy was instrumental in the temporary recapture of Yantai and Weihaiwei in northern Shandong. Aside from occasional gunnery support to ground forces engaged near the coast, there were no further offensive actions in the naval sphere.

As Kuomintang fortunes declined in the campaigns ashore, the navy was more frequently called upon to aid in retreats. Using amphibious landing ships, the navy extricated forces trapped in coastal pockets and transported them south to areas not yet under Communist control. The navy itself was affected by the Nationalists' great southward retreat: By December 1948, its main operating base in Northern China, Qingdao (Tsingtao), was cut off by the Communists, leaving the navy some 250 miles from the nearest Nationalist territory. The large Qingdao naval training center, along with such base facilities as could be disassembled, was evacuated to Taiwan. Indeed, over the next year, the R.O.C. Navy was engaged almost entirely in transporting more than 600,000 military personnel and 2 million civilians from the Chinese mainland to Taiwan.3 Chiang Kai-shek himself was ferried across in a navy destroyer.

Demoralization in the Nationalist Navy

By no means did the entire navy evacuate to Taiwan. The R.O.C. Navy was not immune to the mass defections to the Communist side that marked the latter stages of the civil war. These defections played a minor role in the further demoralization of the Kuomintang government; more importantly, they formed the foundation of the navy of the People's Republic of China.

By the latter 1940s, morale in the R.O.C. Navy had sunk to a very low level. Pay was impossibly meager, and officers were unable to survive without outside income. As in the army, corruption was rife. To supplement their pay, many officers sold sailors' rations and other essential supplies for their own profit, causing a further decline in morale and also in operational readiness. Corruption was, if anything, more intense at the highest command levels in the navy, and it was matched only by high-level incompetence. The navy commander, Vice Admiral Gui Yongjin, was an army officer by background and cared little to learn about the navy he commanded. In addition, high-level operational decisions were made more on the basis of factional politics or illegal profit than good sense and professional expertise.4 Most of the bright young officers and sailors sent off to study in the United States and Great Britain in the 1930s and early 1940s were dedicated to the creation of a strong Chinese navy and knew that this could not be accomplished under the Nationalist regime. Many were thus susceptible to the appeals of the Communists to defect for the good of China.

The first significant incident occurred in February 1947. The destroyer escort Tai He, newly transferred to Chinese hands from the United States, called in Pearl Harbor as it proceeded en route to China.5 The ship was sabotaged by dissident crew members—perhaps Communists— while it was at the Pearl Harbor naval base, and its departure for China was delayed.

Early in 1949, entire ships began to defect to the Communist side. The first was the naval icebreaker Zhang Bai, which left Dagu in the Bohai Gulf for Qingdao on 6 January.6 When the ship failed to appear at Qingdao, it was reported as probably sunk at sea by a storm that was passing through the area. It soon became clear, however, that Zhang Bai had gone over to the Communists. On 13 February, the destroyer escort Huang An left Qingdao without authorization, with 1 officer and 65 sailors embarked.7 It, too, joined the Communist forces. The first major naval defection, that of Chongqing, the new cruiser and flagship of the Chinese fleet, followed close on the Huang An incident. For many reasons, the defection of Chongqing symbolized the problems then bringing about the downfall of the R.O.C. Navy.

Chongqing arrived in Shanghai from Britain, manned by Chinese, in August 1948. Immediately, the navy's endemic demoralization began to affect Chongqing's crew. They lost their relatively high overseas pay and found that it was necessary to compete with corrupt shoreside officers for the ship's rations and supplies. There were many desertions. The captain, Deng Zhaoxiang, made his complaints known to his superiors, was immediately suspected of disaffection, and was put under surveillance. Adding to navy headquarters' suspicions was what Deng himself later described as his "lack of enthusiasm for the civil war."8 It is little wonder that Deng was slated to be relieved in February 1949 as commanding officer by Lu Dongge, a protege of the navy commander. Lu was described by a U.S. intelligence report of the time as "comparatively incompetent." On the evening of 24 February, Chongqing lay at anchor near Shanghai, fueled and ready for sea. Both Deng and Lu were aboard. It appears that at that moment Communist sympathizers in the crew led a mutiny aboard Chongqing, giving Deng and the other officers the choice of joining their defection or facing the consequences. Deng joined; Lu, it is reported, was thrown overboard.

In the early hours of the 25th, Chongqing put to sea and headed north. It arrived at the Communist-held port of Yantai in Shandong the following day. The R.O.C. Air Force searched for the cruiser and, after locating it on the 1st of March, sent four B-24s to bomb it. Only slightly damaged, Chongqing retired to Huludao, on the northern shore of the Bohai Gulf. The air force found the cruiser again and launched several more attacks without success. Finally, on 21 March, Chongqing was hit on the stern and damaged. According to Deng, "The People's Liberation Army decided not to risk our lives defending the ship. They moved us 500 officers and men away to safety and let the cruiser be sunk."9 U.S. intelligence reports at the time, however, indicated that Chongqing was hurriedly stripped of all easily removable equipment; machinery was coated with grease to protect it, and the pride of the Chinese navy was scuttled to prevent further damage or possible defection back to the Nationalist side. Also removed, no doubt, was the R.O.C. Navy's emergency fund of a half million silver dollars being stored aboard Chongqing against the time when the naval command had to evacuate Shanghai.

A second and more devastating naval defection occurred in April 1949. The R.O.C. Navy's Second Squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Lin Zun, was assembled in the Yangzi (Yangtze) River in late 1948 to prevent the Communist armies from crossing as they advanced southward.10 Some 26 ships and craft, ranging in size from destroyers to gunboats, were stationed between Shanghai and the waters above Wuhan, more than 600 miles* from the coast. Perhaps none too hopeful of their success, navy Commander Gui affirmed in February 1949 that the navy was determined to hold the Yangzi line "until forced to withdraw." The Communists reached the river in the spring of 1949. In April, Lin Zun defected, taking 25 of the 26 ships of the Second Squadron—and 1,200 trained sailors—with him. It was later reported in Chinese Communist accounts of the incident that the party had had agents in place in the Second Squadron since June 1948, ready to move when the necessity arose. Whether Lin was carried along by events as Chongqing's Deng Zhaoxiang had been remains unclear.

The navy figured no further in the civil war, except as a means to evacuate the Nationalist forces first southward and then to Taiwan. By February 1949, navy headquarters in Nanjing (Nanking) was down to a skeleton staff of 200, the rest having moved to Shanghai so as not to be caught inland when the time came to move.11 In May, as the Communists approached Shanghai, the R.O.C. naval staff evacuated to Taiwan and the Penghu (Pescadore) Islands in the Taiwan Strait. A new naval headquarters was set up in Gaoxiong (Kaohsiung). Depleted, demoralized, and disorganized, the Nationalist navy awaited the invasion from the mainland that all expected and few believed could be resisted successfully.

The Soviet Naval Presence in China, 1945–1949

The Soviet naval presence in the Lushun (Port Arthur) area of Liaodong Province in Manchuria from the end of World War II on was an important factor in Chinese maritime affairs in the immediate postwar period. The Soviets had long coveted Lushun, and had "leased" it from the Manchu empire in 1898. They were forced out by the Japanese in 1905, however, as one result of the Russo-Japanese War. Forty years later they returned, following their belated entry into the war against Japan in August 1945. According to the terms of the Sino-Soviet agreement of 1945, Soviet occupation of Lushun was permitted only until the end of the war and then only jointly with Nationalist forces.12 Predictably, the Soviets refused to leave. Because no peace treaty had yet been signed between the U.S.S.R. and Japan, they claimed that the war was not yet over. An occasional, nominal Nationalist presence was permitted to enter Lushun, but essentially the strategically positioned naval facility was kept solely in Soviet hands. By August 1946, the Soviet Pacific Fleet had some 5,000 naval personnel at the baXe, along with 19 patrol craft and a number of torpedo boats. By mid-1947, 4 submarines had been moved to Lushun from Vladivostok. The number of submarines grew to about 14 by 1948. Added to this was the presence of some 20,000 Soviet ground troops on the peninsula. With some reason, the Nationalists complained that the Soviets were allowing Chinese Communists free run of the occupied area and in fact were allowing a certain quantity of supplies through the port to the rebel forces as well. As will be discussed below, the Soviet navy in Lushun came to play an important role in the development of the nascent navy of the P.R.C.

Chinese Communist Naval Forces, 1945–1950

To a small degree, the initial development of Chinese Communist naval forces can be dated from late 1945, when Soviet occupation forces in Manchuria turned over to the Communist Chinese between 20 and 30 Japanese gunboats on the Sungari River in Manchuria.13 This riverine force, far removed from the focus of conflict in the civil war, never amounted to much.

The Impetus for Naval Development

The Soviets seem to have been the driving force in the first significant moves toward the establishment of a Chinese Communist naval force. In late 1946, they established at Dalian (Dairen, part of the occupied Liaodong peninsula naval complex) the Democratic Naval Academy for future Chinese naval officers.14 A training school for enlisted sailors was established at about the same time inland at Jiamusi, near the Soviet-Manchurian border. Information on the early course of study and student enrollment is sketchy, but it is clear that virtually all instructors in technical naval subjects were Soviet naval personnel. By mid-1948, the Dalian academy was reported to have graduated some 300 cadets, and new students were being conscripted from the youth of coastal Shandong Province. U.S. intelligence reports of the period noted that one focus of the curriculum was submarine training. This included familiarization on the Soviet submarines based in Lushun, and by late 1948 some 100 graduates of the Dalian Democratic Naval Academy were reported en route to Vladivostok for further training in submarine warfare. In November 1948, the first formal Communist naval force, the Northeast Navy, was established. It comprised little in the way of operating forces, but rather was an organizational structure for the developmental and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Sources and Transliteration

- Introduction

- Part 1 The End of World War II Through the Sino-Soviet Break

- Part 2 The Sino-Soviet Split Through the Fall of Lin Biao

- Part 3 Maritime China Since the Fall of Lin Biao

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index