![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Sexual abuse, and in particular sexual crimes perpetrated against women and children, has become widely acknowledged as a social problem in the United Kingdom. While it is important to acknowledge that sexual crimes are among the most under-reported (Grubin 1998; Scarce 2001; Myhill and Allen 2002; Fisher and Beech 2004; Walby and Allen 2004), they accounted for only 5 per cent of police recorded violent crime, and 0.9 per cent of all police recorded crime in 2003/04. In addition, research evidence generally reports lower reconviction rates for sexual offenders than for perpetrators of more routine crimes, such as theft and burglary (Hanson and Bussiere 1998). A study conducted by Hood et al. (2002) found that under 10 per cent of sex offenders were convicted of another sexual offence within six years. Nonetheless, public concern with the risks posed by sexual offenders is undisputed.

The public's highly emotive response to sexual offending has clearly been fuelled by media representations of sex crime and, in particular, the newsworthy value of the worst cases. The image of the sex offender that looms large in the press is that of an amoral, manipulative, predatory sociopath who preys on those persons in society, women and children in particular, who are considered most vulnerable (Greer 2003). Such powerful imagery succeeds in creating the inaccurate and misleading impression that sex offenders are somehow inherently different from the rest of society and are in need of treatment and management different from other types of offenders. This has led to growing pressure on the criminal justice system to protect communities from sexual offenders in their areas.

Current legislative responses have resulted in an increase in the number of sexual offenders receiving custodial sentences and for longer periods of time. However, the public's demand for draconian sentences is coupled with the expectation that something will be done to reduce the risk of future sexual offending. In the light of this, since the late 1980s there has been increasing recognition of the potential of reducing re-offending through treatment programmes. At the same time, in contrast to earlier more optimistic penal philosophies, where treatment programmes are undertaken they are no longer expected to ‘cure’ sex offenders but rather to help offenders control their behaviour in order to minimize the risk of them re-offending. To this end, stringent measures designed both to control and monitor sexual offenders in the community have also been introduced over the same period.

While a considerable amount of research and writing has been devoted to the treatment and management of sex offenders, one perspective notable by its virtual absence has been that of the offenders themselves. This book aims to fill that gap by exploring sex offenders’ perspectives of initiatives designed both to control and manage their risk of re-offending. I followed and interviewed 32 male sex offenders between 2001 and 2003 over the course of their participation in a number of prison-based and community-based treatment programmes. Each participant was about to start one of three sex offender treatment programmes, namely the prison-based Sex Offender Treatment Programme (SOTP) and the Behaviour Assessment Programme (BAP), and the probation-led Community Sex Offender Groupwork Programme (C-SOGP).

While the book focuses on adult male sex offenders it is important to note that a third of all reported sexual offences are committed by the under-18 age group (see Richardson et al. 1997; Grubin 1998; Masson 2004 for a summary). Female sex offenders also make up approximately 0.5 per cent of all sex offenders in prison (28 females compared to 5,550 male sentenced prisoners in November 2003),1 although the actual number of female offenders is considered to be much higher (Fergusson and Mullen 1999). Arguably, the true extent of female offending is difficult to determine given that in Western societies women are ‘permitted greater freedom than men in their physical interactions with children’ (Grubin 1998: 23). It is also perhaps too disconcerting to think that either women or children (precisely those members of society who are thought to be in need of protection from sexual abuse) are capable of committing such acts (Crawford and Conn 1997; Hetherton 1999; Kemshall 2004).

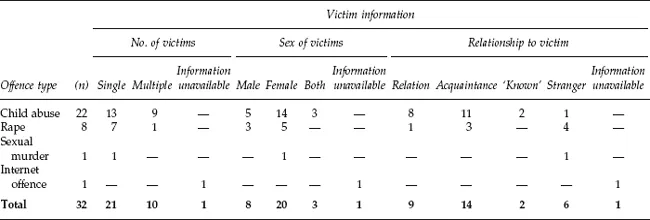

It should also be acknowledged that despite the growing preoccupation with the ‘predatory paedophile’ and ‘stranger danger’, sexual offending is not a homogenous act. There is of course a wide array of sexual offences ranging from what is commonly regarded as the less serious end of sexual offending, for example exposure, through to sexual murder (Fisher and Beech 2004). The men who participated in this research had committed the following types of crimes.

Child abuse

The majority (n = 22) of the men participating in this research had committed child abuse. Their offending behaviour ranged from non-contact offences to serious penetrative offences. Only one of these men had abused a child that was unknown to him.

Rape

Eight of the men who agreed to take part in this research had committed rape. Rape is defined here as a penetrative sexual act on an adult. Four of these men had raped a stranger; this applies to cases where the perpetrator had no contact with the victim prior to the abuse.

Sexual murder

Although there is no offence of sexual murder in the British legal system, offenders convicted of murder or manslaughter can participate in sex offender treatment programmes if there is an apparent or admitted sexual element to the crime (Fisher and Beech 2004). One participant had been convicted of murdering his victim. Although he was never charged with a sexual offence, forensic evidence suggested the possibility of a sexual assault. These details included a single matching pubic hair on the victim's cardigan, the fact that the victim's bra was ripped, and that her top was pulled over her head.

Internet offences

Finally, one research participant had been convicted of an internet offence. This involved downloading child pornography from the internet.

Table 1.1 presents a more detailed summary of the research participants’ current offences, including information regarding their victims’ sex and relationship to the perpetrator. Four categories have been used to describe each victim's relationship to the participant. The definition used to categorize offences committed against ‘strangers’ covers instances where the suspect had had no contact with the complainant prior to the abuse. ‘Acquaintance’ refers to cases where the victim was known to the participant. This might also include instances where the victim was ‘groomed’ over a period of time. The ‘relation’ category includes instances where the victim is a member of the participant's extended family. This includes stepchildren as well as nieces and nephews. Finally, the ‘known’ category includes cases where the offender abused multiple victims, where some of his victims were relatives and others were acquaintances.

Table 1.1 Research participants’ profile

As can be seen from the men participating in this research, sex offenders are not a homogenous group. These men also present different patterns of behaviour, different motivations for their behaviour and different levels of need. In addition, just as there are different types of sexual offences, men who commit such crimes have varying personalities and identities. This book is therefore interested in how the highly emotive and punitive social climate that surrounds the issue of sexual crime affects a sex offender's presentation of himself, and ultimately his ability to self-manage his risk of re-offending.

The structure of the book

The book is divided into three main parts. The first provides an overview of the measures in place both to manage and to treat sex offenders. Chapter 2 outlines the legislative response to sexual offending in England and Wales over the last two decades. In so doing, it outlines the continual trend of bifurcation and in particular the increasing, and overtly punitive, measures taken against sex offenders in sentencing. The chapter also starts to explain the current moral panic and obsession with sexual offenders by raising questions relating to the underlying debates that have shaped the new culture of crime control (Garland 2001).

Chapter 3 examines the role that rehabilitation plays in contemporary criminal justice policy. In particular, the chapter focuses on the new management styles and working practices that have been increasingly implemented in rehabilitative intervention with all offenders. The chapter then describes the current situation regarding sex offender treatment provision in prison and community settings. In doing so, it provides a brief overview of the three sex offender treatment programmes used in this research. Each programme is described in terms of eligibility criteria, programme content and style of delivery.

Part II provides an empirical account of the participants’ perceptions of how they are ‘treated’ and ‘managed’. Chapter 4 begins by exploring the participants’ views of the ways in which the public perceive and react to sexual offending. Of special importance here is the effect that this has on the way they manage their identity. Drawing on Goffman's (1963) notion of impression management, the chapter explores how individuals with a conviction for a sexual offence construct their identity by differentiating themselves from negative attributes typically associated with sex offenders. In doing so, the chapter presents the subjective accounts of three groups of participants, who have been labelled as ‘total deniers’, ‘justifiers’ and ‘acceptors’, in order to highlight similarities and differences in the way they attempt to preserve a more acceptable image, unencumbered by the popular image of the sex offender.

Chapter 5 explores participants’ decisions to start and complete treatment and the extent to which this is indicative of their state of denial. Consequently, the chapter concentrates on how personal, legal and temporal pressures might influence an individual's decision to take part in treatment. The chapter also goes some way in exploring the reasons given by participants for failing to complete their respective treatment programme, and the implications for their risk of future offending. This chapter is concerned with the participants who failed to complete treatment for reasons other than re-offending.

The next three chapters explore the participants’ views regarding their involvement in treatment. Chapter 6 is divided into two main sections. The first explores the participants’ perceptions of the group-work approach to treatment. In particular, it examines the relationship between the research participants, other group members, and the programme facilitators. In doing so, it examines the extent to which the group environment is conducive to the development of attitudinal and behavioural change. Following on from this, the second section explores whether the participants felt pressured to conform to the theories used within treatment to rationalize sexually abusive behaviour. This section traces the tensions and contradictions between programme content and the participants’ construction of identity.

Chapter 7 then explores the participants’ accounts of ‘what works’ in treatment, taking into consideration both the legal and formal obligations entailed in participating in treatment, and the demands of a process that is designed to reduce a person's offending. Within this context, the chapter examines how effective the main areas addressed in sex offender treatment programmes are at providing group members with the necessary skills to minimize their risk of future offending.

Chapter 8 traces the experiences of the two men taking part in this study who re-offended while participating in treatment. It begins by exploring the extent to which they felt they had benefited from treatment intervention. It also explores their fears of disclosing their risk of offending within a group setting. Having touched on this question in Chapter 6, Chapter 8 considers more fully the implications of conducting treatment in a group environment. In particular, the chapter explores the participants’ desire to maintain an identity that is upheld and accepted by the group. To this end, the rest of this chapter explores all the participants’ views on the measures designed to manage their risk of future offending in the community. Particular attention is paid to the sex offender register and the issue of full public access to the information contained in the register, in the light of the ability of such measures to prevent re-offending.

Finally, Part III sets out the conclusions of the book and offers some tentative suggestions on how best to deal with the threat posed by sexual offenders.

Lasting impressions

Scully (1990), in her study on convicted rapists, reported that curiosity about why and how her research was done was often greater than interest in the findings. Consequently, she was continually asked the same two questions whenever she presented her work: ‘What motivated [her] to undertake the project, and what kind of experience was it for [her], a women, to be confined daily in prisons talking face to face with men convicted of rape, murder, and assorted other crimes against women’ (Scully 1990: 1). Similar questions were repeatedly asked during this research study.

A quick answer to the first question is that as researchers we are similarly affected by moral panics. Thus, the main motivation for conducting this research was to determine how best to deal with sexual offenders in order to prevent future victimization. However, perhaps the most important thing I have learnt from conducting this study is that being a researcher does not provide you with any immunity from the intensely emotional issues that arise from research of this kind.

One of the biggest problems that I had to deal with was my need to justify repeatedly the reasons for undertaking this research. Returning to that first question then: What motivated me to undertake this study? I interpreted this question as a signal of disapproval and/or disbelief that someone would choose to sit in a room and talk face to face with convicted sex offenders. This feeling was accentuated by the fact that I came to like some of the men who participated in the research. On the one hand I could justify this safe in the knowledge that these men had multiple identities (see Chapter 4), and hence it was possible to like them while simultaneously maintaining a strong repulsion for what they had done in the past. But on the other hand it was hard to hold on to this balance when the popular view is to reject everything about them.

Another key problem was how to cope with listening to the participants’ accounts of their offences repeatedly over the course of the research. The majority of participants were interviewed at three different stages of their treatment: before the treatment began, during the course of treatment and after the treatment programme had been completed. I felt that the best way to manage the emotional burden of their stories was to block it out when not engaged in this research. However, by not sharing how I felt about these accounts with others, my own thoughts and feelings were allowed to mount. Eventually this became too much to deal with alone. This caused great anxiety for myself, often resulting in emotional outbursts. On such occasions there was usually a trigger incident. For example, after conducting an entire week of interviews with participants attending the SOTP I found myself in a shopping centre crying. In front of me were two children of a similar age to one of the participants’ victims. In his interview the participant had been both flippant and meticulous in the way he spoke about and described what he did to his victims. However, while the children I saw in the shopping centre reminded me of his victims, they were simply the catalyst for releasing the emotions that I had hidden away.

I also became aware of how the accounts that I had heard affected the way I perceived others and certain situations. For example, one of the participants had been a bus driver. He was convicted of murdering a woman who boarded his bus after it was no longer in public use. Over a year later I found myself aboard a bus in a location that I was unfamiliar with. I had asked the bus driver to tell me where to get off. Over the course of 20 minutes the bus gradually emptied of passengers until the point where I was alone on the bus with the driver. Immediately, my anxiety of the situation was heightened, made worse by my recollection of what I had been told in the interview with my participant. Although many people probably feel a little anxious about being alone on a bus, I became extremely frightened. As it turned out the ...