- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

At the end of the eighteenth century, Alexandria was a small unimposing town; less than a century later, the city had become a busy hub of Mediterranean commerce and Egypt's master link to the international economy. This is the first study to examine the modern transformation of the city, the surges of internal and international migration; the spa

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Colonial Bridgehead by Michael J Reimer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Geographical and Historical Inheritance

1

Between Egypt and the Sea

The Geography of the Alexandria Region

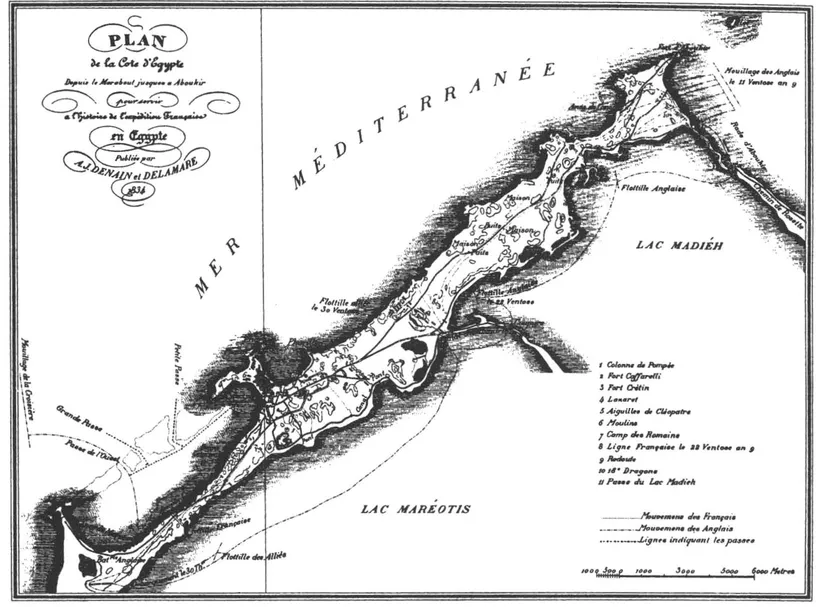

Alexandria is located on a narrow isthmus separating Lake Maryut from the Mediterranean Sea. The narrowest part of this isthmus, which is the city's immediate hinterland, is scarcely a kilometer across, although the isthmus widens out as it joins in the southwest to the Libyan desert and in the northeast to the headlands of Abu Qir (see Map I).1

Early in the Pleistocene epoch, this area was not connected to the Nile valley. What later became the Alexandria isthmus consisted of elevated ridges of oolitic limestone fronting the Mediterranean and extending from northwestern Egypt toward what is now Abu Qir. The mouth of the Nile in this period was far to the south and east, only some 33 kilometers north from the area of present-day Cairo. As the Nile brought down its annual discharge of mud and silt, alluvial deposits began to build up the Delta. This process was not, however, uniform or continuous, since there were substantial fluctuations in the level of the Mediterranean sea during the Pleistocene, causing major changes in the position and contours of the coastline. The general tendency, however, was for the level of the sea to fall relative to the land. By late Paleolithic times, the Mediterranean coast had advanced some 181 kilometers north of Cairo (from which it has receded to its present position, 170 kilometers north). As the Delta bulged northward, the great lakes of northern Egypt were formed. The northwestern coastal ridges became directly linked to the expanding Egyptian landmass on both sides of Lake Maryut. However, it is worth emphasizing that the Alexandria area, though joined to the Nile valley, remained geologically distinct from the Delta. The limestone substructure of Alexandria is quite different from the thick alluvial muds and fiuvio-marine sands and gravels underlying the Delta.2

These ridges of limestone ran parallel to the present-day seacoast and are the outstanding physiographic feature of the isthmus. The highest ridge consists of a range of hills, averaging about thirty meters in height, that have long been quarried by the coastal inhabitants for building materials. There is also a second, lower ridge that runs parallel to the first, just behind the Mediterranean beaches. It disappears under the sea just to the west of Alexandria, but reemerges as a chain of rocky islets, of which the cape of Ra's al-Tin was originally part. There is some archaeological evidence that suggests that these islands along the northern coast may have served as a prehistoric port.3 After the founding of the city of Alexandria by Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., a seven-stade causeway—hence Heptastadion—was built to connect one of the islands, the island of Pharos as it was then known, to the mainland, with the object of developing the port. The discharge of mud and silts through the ancient Canopic mouth of the Nile and, probably, the dumping of debris into the harbors, gradually built up against the causeway, giving rise to a distinctive hammerheaded peninsula that juts out into the Mediterranean.

The flow and interaction of its surrounding bodies of water—the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile River, and Lake Maryut—have had a decisive influence on the history of Alexandria. It is significant to note that the direction of the current in the southeastern Mediterranean sets toward the east. The primary reason for this is the low level of water in the Mediterranean relative to the Atlantic, which creates a natural influx from the ocean and results in a general eastward current. However, as this current passes the mouth of the Nile, it slows due to the resistance of the river's discharge. Also, as one would expect, there is a wide arc of shallow sea along the northern coastline. This explains why the port of Alexandria has an advantage over the ports lying farther to the east, such as Rashid and Dumyat. Situated at the extreme northwest corner of the Delta, it is the least exposed to the accumulation of silt brought down by the Nile. The shallow areas of sea north of the Delta have posed continual problems for mariners along this stretch of coastline, known for its shifting local currents and treacherous sand bars. In addition, the towns of the northern Delta have been affected by slow but substantial shifts in the bed of the river's lower branches. Although some silting-up does occur at Alexandria, it does so at a much slower rate than at either Rashid or Dumyat, both because these ports lie in the flood plain of the Nile and because the Mediterranean current tends to bear mud and silt away from Alexandria to the east.4

Map 1. Alexandria Coastal Region from 'Agami to Abu Qir (1834)

The complete obstruction of the ancient Canopic branch of the Nile around the twelfth century by alluvial deposits has presumably slowed the silting of Alexandria's harbor even further. The blockage of the Canopic branch had a significant effect on Lake Maryut as well. In antiquity the lake occupied a much larger proportion of the Maryut depression than at present. It served as a source of fresh water for the inhabitants of the surrounding area in ancient times, was surrounded by vineyards and olive orchards, and was famous for its commerce and fisheries.5 To facilitate the movement of ships, artificial channels linked Lake Maryut to the Canopic Nile and to the Mediterranean Sea. As it appears, the chief engineering problem in antiquity was to prevent the lake from rising during the flood season and inundating the towns along its shores. But the disappearance of the Canopic branch in medieval times and the slow subsidence of land in the Alexandria area, radically altered the situation of Lake Maryut. No longer replenished by the annual inundation of Nile waters, evaporation caused a rapid shrinking of the lake and a fast increase in salinity. One Egyptian irrigation engineer estimated that, because of the shallowness of the lake, it would take no more than four years for the lake to become dry and salt encrusted, unless Nile waters were diverted into its basin. In fact, when the French arrived in 1798, the lake had become no more than a sandy plain, of which the lowest portions retained some rainwater during the winter.6

Finally, there are the influences of climate, and in particular the winds, upon the situation of the city. Like the rest of Egypt, the northern coast is characterized by a paucity of rainfall, although there was clearly much greater rainfall in ancient times than at present, and this area still gets more rain, on the average, than other parts of the country. The local weather pattern can be described as rainless, sultry summers and cool winters with considerable, if erratic, rainfall. The temperatures are moderate in comparison with the often intense heat of the interior, which is why Egyptians are so enthusiastic about a holiday in 'Iskandariya.' More important from the standpoint of navigation, clouds and fog only rarely obstruct visibility near the city.7

The critical factor in the era before steamships was, of course, the direction and force of the wind. In this regard, too, Alexandria was blessed. While the northerly winds that prevail throughout most of the year favor the quick passage of ships from, for example, Rhodes to Alexandria, the same winds can turn violent and destructive, especially in the winter, jeopardizing ships sailing and anchoring along the southern Mediterranean. It was just such a tempestuous northeastern wind that blasted the ship carrying the Apostle Paul to Rome, causing it to founder near Malta.8 Hence the wisdom of the Aegean proverb, "Get under sail with a young south wind or an old north wind."9 Even Alexandria's eastern harbor had this disadvantage: it did not provide sufficient protection from northern gales. But the western harbor was a perfect haven from the winds, virtually the only one in the southeast Mediterranean. Thus, Napoleon Bonaparte declaimed, with more than a little exaggeration: "All the fleets of the world could anchor here, and in this ancient port, would be sheltered from the winds and from every attack."10

Alexandria’s Pre-Ottoman History

Before the founding of Alexandria by Alexander, the area was occupied by a cluster of villages, the chief among them called Rhakotis.11 The Greek geographer Strabo claims that the site was fortified by the pharaohs for the purpose of restricting the importation of foreign goods and to fend off Greek marauders.

Content with what they had, and with no real need of imports, they were hostile toward all who sailed to their shores, and particularly the Greeks (for they were pirates and desirous of foreign land through their lack of it); and they established a guard-post in this place, with orders to repel all comers; and they gave the guard for dwelling the region called Rhakotis, which is now that part of Alexandria lying above the shipyards, but was then a village. And the region round about the village he gave to herdsmen, who were also able to resist foreign intruders.12

Strabo's remarks sound several of the leitmotivs in Alexandria's history. While the self-sufficiency of Egypt is probably overstated, the passage makes clear that the gateway to Egypt was this peculiarly accessible stretch of coast. Recognizing its vulnerability, the rulers of Egypt posted a guard against predatory Mediterraneans. In a provocative analogy to the events of Bonaparte's invasion, 'herdsmen' (like the Bedouin) were empowered to resist intruders, which calls to mind Alexandria's propinquity not only to the sea but to the desert.

The antecedents are important, but unimpressive.

Like that other great entrepôt of the eastern Mediterranean, Constantinople, the birth of Alexandria was part of a drama of world politics. Thus, in 331 B.C., Alexander of Macedon seized upon Rhakotis as the site for a city. He helped to design the city, intending that it command the commerce of east and west, and become a nursery for the germination of a new religious and cultural synthesis. Moreover, the city was to serve as a link to Greece and a memorial to his name. He succeeded beyond his dreams, since Alexandria became the supreme commercial and cultural center of the ancient world, outlasting Alexander's empire by many centuries.

The auspiciousness of the choice was confirmed soon after the foundation of the city. With a splendid climate, ample limestone quarries, plentiful fresh water, and an energetic imperial administration, the city was poised for expansion. It required, however, a good harbor. The island of Pharos afforded a degree of protection to ships at anchor along the coast, but Alexander's plan called for improving the port by building a causeway to connect the isthmus to the island. This feat of engineering (actually completed under the Ptolemies) created a double harbor by breaking the force of local currents, creating secure anchorage especially on the western side of the mole. The eastern harbor (the Great Harbor of antiquity, so-called because of its greater depth) gained in protection from the building of the causeway as well, though much more from the eventual addition of breakwaters projecting from Silsila and the eastern tip of Pharos.13

A short time after its establishment Alexandria had become one of the greatest cities in the Mediterranean basin. It prospered as Egypt's first port, and from its intermediate position between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which was a through-route in antiquity. The Ptolemies, the successors of Alexander in Egypt and Syria, set out to embellish the city still further by the construction of the great lighthouse of Pharos, over 120 meters in height (located at the site of the recently restored Qayt Bey Fortress). They established the Mouseion (whence our word 'museum'), a scientific academy with laboratories, lecture halls, observatories, and a world-famous library. While the population of the city in antiquity cannot be determined with much accuracy, it is certain that it reached several hundreds of thousands by late Ptolemaic times (around the first century before Christ). The remark by one Greek traveler that Alexandria was the largest city in the world suggests that its population may even have approached one million. In any event, it enclosed a population of tremendous diversity: Greeks, Persians, Egyptians, Syrians, Africans, Jews, Romans, and many others.14

When the Arabs conquered Egypt in 642, Alexandria was still an imposing city with a population of perhaps three hundred thousand.15 Though much of its cultural richness had been dissipated—the Mouseion with its great library had long since disintegrated—it remained a force to be reckoned with in terms of cross-cultural trade and ecclesiastical politics. The conquest probably had little immediate effect on the level of population. The Arab Muslim conquests, unlike the later migrations of nomads from the steppes of Central Asia, caused relatively little destruction to the existing material civilization of the Middle East. On the contrary, the unification of an immense belt of territory under a single administration stimulated the growth of cities. Moreover, the Arabs had no innate aversion to the sea, as has sometimes been suggested. Although they did not have a navy in the early years of the conquest, they soon developed one that carried the war to Constantinople itself. Muslim navies and merchant shipping dominated the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Serias Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables, Maps, and Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART ONE The Geographical and Historical Inheritance

- PART TWO Muhammad Ali's City, 1807−1848

- PART THREE Bridgehead of Colonialism, 1848−1882

- Appendix: Census Documents

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index