eBook - ePub

Neoliberalism, Transnationalization and Rural Poverty

A Case Study of Michoacán, Mexico

- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neoliberalism, Transnationalization and Rural Poverty

A Case Study of Michoacán, Mexico

About this book

Carlos Salinas's government drew praise from many academic commentators and foreign governments for its boldness in embarking on neoliberal economic reforms that tackled some of the shibboleths of the Mexican revolutionary tradition and for its supposedly astute political management of change. This book offers a more critical understanding of the e

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neoliberalism, Transnationalization and Rural Poverty by John Gledhill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Introduction: Structural Adjustment, Neoliberalism and the Mexican Countryside

For a majority of the world's population, the 1980s was a lost decade. Even in the metropolitan countries, rising prosperity for some was counterbalanced by an escalating polarization of income distribution, rising unemployment and growth in the number of families living below the poverty line. Yet as conditions worsened in the North at the start of the Nineties, the leaders of the "First World" insisted that their policies had been virtuous. Recession was explained as a product of global forces, including the failure of the world economy as a whole to move far enough towards the deregulation and free market policies which would guarantee future growth. The North's advice to the South was to persevere with policies of "structural adjustment" despite the high social costs of those policies in countries which lacked effective public welfare systems, systems which northern governments themselves were now claiming that their own societies could no longer afford to maintain in their existing forms, in the face of fiscal crisis and ageing populations.

Even the most schematic account of the costs reveals the magnitude of the sacrifice demanded and the size of the gap a longer-term renewal of growth is being asked to bridge. In the case of Latin America, the richest 5% of the population maintained or increased their incomes through the Eighties, whilst the bottom 75% suffered a decrease. Consumption per capita declined by 25% for labor between 1980 and 1985, but rose by 16% in the case of owners of capital (Ghai and Hewitt, 1991: 21). According to a United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America study of Mexico, Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina and Chile, the number of people living in absolute poverty in those counties increased from 136 to 183 million individuals, equivalent to 44% of the total population (CEPAL, 1992). Increasing poverty was associated with massive rural-urban migration: in 1970, 37% of the Latin American poor lived in cities, whereas 55% were urban by 1986. Yet rural poverty remains endemic. In 1990, Mexico's National Solidarity Program (PRONASOL) identified the seventeen million persons living in "extreme poverty" in the country as predominantly inhabitants of rural communities. In Latin America as a whole, around 54% of the rural population were estimated to live below poverty level in the mid-Eighties (Ghai and Hewitt, op.cit.: 23) and 43% of rural households in Mexico were in this condition at the start of the next decade.

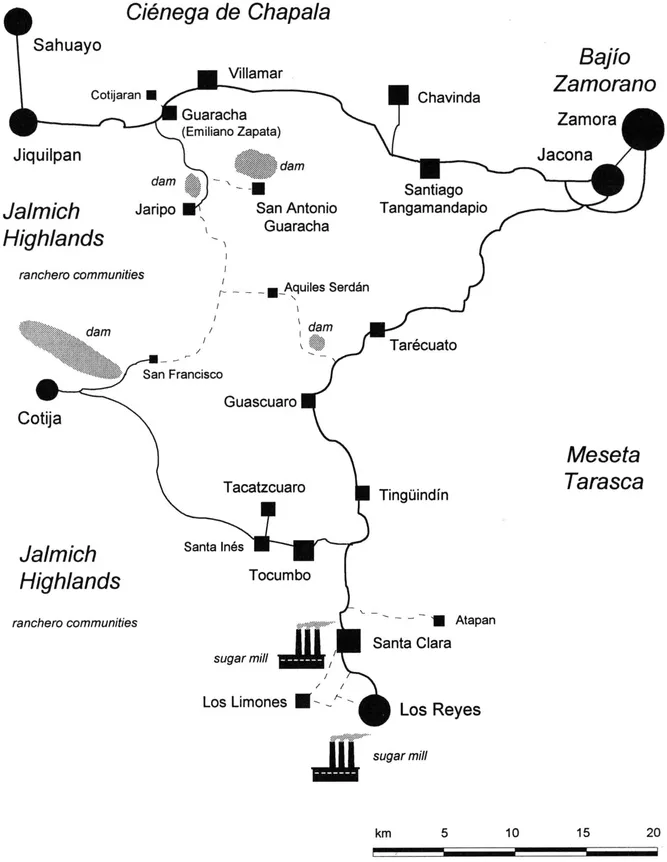

FIGURE 1.1 Map of the State of Michoacán

The direct impact of the stabilization policies mandated by the IMF fell in the first instance on the public sector, although the broader structural adjustment package, with its emphasis on opening up the domestic economy to the forces of international competition, also put the squeeze on small and medium sized firms in the private sector in Mexico. This was because the Mexican government opted for strong trade liberalization and reduced protection for national producers without waiting for reciprocal concessions from the country's metropolitan trading partners. Nevertheless, in the early phases of adjustment, public sector pay was cut in real terms more than private sector pay, and many public sector jobs were eliminated entirely. It is easy to denounce the unproductive nature of the massive public sector job creation associated with statist development—although there is a cruel irony in the fact that some of the most venal of former bureaucrats have been able to take their place at the forefront of the new free-market enterprise culture, whether we are talking about Latin America or the former Soviet Union.

There is, however, another side to the picture. In the first rural area which I studied in the state of Michoacán, the Cienega de Chapala, public sector employment in manual work was the most significant form of off-farm employment for landless married men at the start of the Eighties. Almost all these jobs have now disappeared, as have some of the minor technical posts occupied by those with more

FIGURE 1.2 Map of the Ciénega de Chapala, Zamora and Los Reyes (showing places mentioned in the text and main communication routes)

education. Even those who worked in the supposed "profession" of school-teaching were earning no more than a field-hand in 1991. In some communities children lost months of education because too many teachers decided to take a working leave-of-absence in the United States.

Austerity meant a dramatic loss of social position for some families: the ECLA survey found that just over 12% of homes on the poverty-line in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela at the end of the Eighties were former middle class families. But if the middle class lost most relatively speaking, the catastrophe was worse for working class people who had less to start with: not only did real wages fall, but labor productivity declined as well.1 Most depressingly of all, the proportion of young people who had neither studied nor worked in the kind of job which would be recognized in official statistics as "employment" was higher at the end of the 1980s than at the end of the 1970s. Much of this youth did not even work within the secondary labor markets which proliferated under the new post-Fordist regime of capitalist accumulation which David Harvey has dubbed "flexible accumulation" (Harvey, 1989: 124). In the new world forged by neoliberalism, the once discredited concept of "marginality" at last seemed to be having its day.

Into the Nineties

The stark aggregate statistics on the costs of a decade of structural adjustment describe the consequences of rural impoverishment coupled with falling urban real incomes and declining opportunities for employment in cities in any kind of stable work, even at the lowest of wages. Yet although the costs of adjustment have been broadly similar, there are differences in the precise policies individual countries have pursued, particularly with regard to the degree of trade liberalization. Further-more, many countries have not pursued a consistent line of policy. Within the broad parameters of structural adjustment and the shift to neoliberal policies, some countries appear to have been more "successful" than others and the jury remains out on whether extreme versions of economic liberalization yield the best long-term results in terms of stabilization and growth. Still more significantly, it is not clear how we should measure "success."

In terms of "recovery" and renewal of economic growth, 1991 did see a general turnaround throughout the region, although the rate of increase in the number of people living in poverty continued to exceed overall population growth. Yet as UNCTAD's economists observe in their 1993 Trade and Development Report, most Latin American countries grew at rates which remained low in comparison with the region's post-war average in 1991 and 1992. If the primary goal is to enter a new phase of export-led manufacturing growth, Latin America has yet to achieve rates comparable to those which underlay the "take-off into export-orientated growth of Asian countries such as Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia and Singapore. Growth has been stimulated more by consumption than by investment, and high current account deficits cannot necessarily be viewed as a benign phenomenon of transition (caused by imports of capital need to finance the restructuring of production necessary to achieve long-term growth). Domestic savings in Mexico actually fell by 3% of GDP in the period 1988-92, and the bulk of foreign capital inflows have been destined for the financial markets rather than direct investment in production. The proceeds of privatizations and incentives to citizens to repatriate capital helped to produce a brighter short-term picture. Yet Mexico's consumer boom of 1990-92 was based on an extension of credit to individuals which the Central Bank subsequently judged imprudent in the light of stagnant real incomes, and the picture on repatriation of capital under the Salinas administration turns out to be less positive on closer inspection. During the period 1989-93, U.S.$11.6bn of flight capital was repatriated, but Mexican deposits in U.S. banks fell by only U.S.$3.8bn (Latin American Weekly Report 94-22: 260). Those deposits still totalled U.S.$15.8bn at the end of 1993—equivalent to 64.5% of Mexico's international reserves—making the country the largest Latin American depositor in the U.S. banking system, and the fourth largest world-wide (ibid.). A new flight of capital, estimated at U.S.$11bn, occurred in the first half of 1994, in the wake of the Chiapas uprising in January, the assassination of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio in March and subsequent fears of a problematic outcome to the August elections.

The economic restructuring achieved by Salinas did not, in itself, lay the basis for sustainable growth. Mexico's commitment to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) encouraged the government to maintain an overvalued currency and a budget surplus even though this caused growth to slow (and unemployment to rise) during 1993. Manufacturing output registered its first fall since 1987 in the second quarter of 1993. The primary sector, including agriculture, fishing and forestry, but excluding mining and crude oil extraction, continues to be the worst performer in the entire economy. Its contribution to GDP contracted throughout 1992. The official figure for open unemployment in Mexico, produced by the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Information (INEGI) increased from 2.9% to 3.3% between May 1992 and May 1993, but using INEGI's alternative measure of "unemployment and underemployment," the proportion of the economically active population earning less than a single minimum wage, the rate rose from 12 to 13%. In the first quarter of 1994, the maquilidora sector showed a strong upsurge of activity, along with the steel industry, but domestically orientated industries, such as shoes and textiles, continued to contract. The particular policy tightness which caused this conjunctural slowdown is reversible, but the deeper questions posed by UNCTAD's survey remain to be answered in the longer term.

The basic presumption of structural adjustment policies is that removal of protection and subsidies from inefficient producers will, in the long term, produce a more rational allocation of national resources. Whatever the short-term costs, countries which accept the disciplines of full incorporation into the world market should be able to maximize growth and provide their citizens with a superior standard of living based on higher productivity and efficient exploitation of the potential gains from specialization in world trade (on the principle of comparative advantage). There is considerable scope for debate about the theoretical validity of this prescription in a "real world" of imperfect markets and historically entrenched unequal development. We need to ask, for example, how much of the "comparative advantage" in the production of a given type of commodity a given country enjoys (or lacks) at a particular moment reflects the accumulated result of its wider pattern of economic development to date, so that only decisions to plan for the future and ignore short-term difficulties can truly realize a nation's economic potential within the international division of labor. At this stage, however, I want to focus on the evidence provided by actual experience. In particular, the question of how far renewed economic growth will produce greater social equity remains as open an issue for the First World as for the Third.

Social and Political Dimensions of Economic Policy: A Broader View

If the performance of countries is measured in terms of the UNDP's Human Development Index rather than per capita GNP, supposed "success stories" like Mexico, Chile and Argentina are seen in a different light (UNDP, 1993). Between 1990 and 1992, Mexico fell eight places (from 45 to 53) in the world ranking on this index, which combines indicators of purchasing power, education and health. Chile and Argentina both continued to rank higher than Mexico but their absolute HDI scores declined. When increasing inequality in income ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: Structural Adjustment, Neoliberalism and the Mexican Countryside

- 2 On Audacity and Social Polarization: An Assessment of Rural Policy Under Salinas

- 3 Social Life and the Practices of Power: The Limits of Neocardenismo and the Limits of the PRI

- 4 The Transnationalization of Regional Societies: Capital, Class and International Migration

- 5 A Rush Through the Closing Door? The Impact of Simpson-Rodino on Two Rural Communities

- 6 The Family United and Divided: Migration, Domestic Life and Gender Relations

- 7 American Dreams and Nightmares: The Fractured Social Worlds of an Empire in Decadence

- 8 Neoliberalism and Transnationalization: Assessing the Contradictions

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Book and Author