Chronicle of the Third Crusade

A Translation of the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi

- 410 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Chronicle of the Third Crusade

A Translation of the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi

About this book

Published in 1997, this is a translation of the Intnerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, 'The Itenerary of the Pilgrims and the deeds of King Richard, ' based on the edition produced in 1864 by William Stubbs as volume 1 of his chronicles and memorials of the reign of King Richard I. This Chronicle is the most comprehensive and complete account of the Third Crusade, covering virtually all the events of the crusade in roughly chronological order, and adding priceless details such as descriptions of King Richard the Lionhearts personel appearance, shipping, French fashions and discussion of the international conventions of war. It is of great interest to medieval historians in general, not only historians of the crusade. The translation is accompanied by an introduction and exhaustive notes which explain the manuscript tradition and the sources of the text and which compare this chronicle with the works of other contemporary writers on the crusade, Christian and Muslim. The translation has been produced specifically for university students taking courses on the Crusades, but it will appeal to anyone with an interest in the Third Crusade and the history of the Middle Ages.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Book 1

Chapter 1: The Lord exterminates the people of Syria because of the people’s sins.

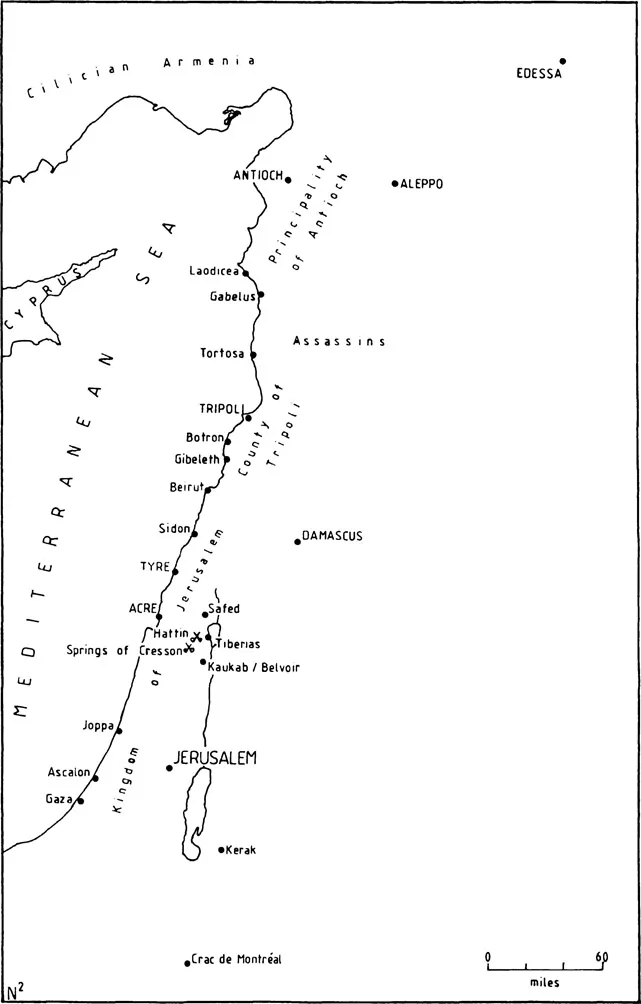

Chapter 2: Saladin routs the Master of the Temple and others [Battle of the Springs of Cresson, 1 May 1187]. 2

Chapter 3: Saladin’s descent and origins.

Chapter 4: Saladin seizes the kingdoms of Egypt, Damascus, India, and other lands.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- List of Maps

- Introduction

- The Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi

- Prologue

- Book 1

- Book 2

- Book 3

- Book 4

- Book 5

- Book 6

- Bibliography

- Index