- 410 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Telechelic Polymers: Synthesis and Applications

About this book

This first-of-its-kind publication reviews the most impor-tant literature on the synthesis, properties, and applications of telechelic polymers. Written by a group of internationally known ex-perts in the field, this text contains a review table which allows the reader to search for given polymers with given end groups. Over 1,250 references are listed, covering primary and review articles as well as patents. Chapters include the preparation of telechelics by stepwise polymerization, anionic polymerization, radical polymer-ization, cationic polymerization, ring-opening polymerization and controlled polymer degradation. Polyols for the polyurethane pro-duction are described, as well as halato-telechelic polymers. Also, a more theoretical contribution on the physical properties of net-works formed from telechelic polymers is provided.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS

I. DEFINITION

The term “telechelic polymer” was proposed in 1960 by Uraneck et al.1 to designate relatively low molecular weight macromolecules possessing two reactive functional groups situated at both chain ends. The term originates from the Greek words telos, far, and chelos, claw, thus describing the molecule as having two claws far away from each other, i.e., at the extremities of the chain, able to grip something else.

Of course, the concept of prepolymers, which can be transformed into final products, with well-specified properties by reaction of end-standing functional groups with multifunctional coupling agents was not new. As early as 1937, Otto Bayer had recognized the potential of this chemistry: “Die neue Methode gestattet zum ersten Male Kunstoffe mit praktisch beliebigen Eigenschaften und eindeutich klarem chemischen Aufbau herzustellen”.2 Hereby he referred to the — at that time newly developed — polyurethane chemistry based on hydroxy-terminated prepolymers and diisocyanates that opened new perspectives of making materials with a wide array of physical properties by controlling the molecular architecture of the polymers. However, the importance of the Uraneck paper was not only scientific but also, or even more so, of a “philosophical” nature. Bayer used polyether polyols as prepolymers for polyurethane synthesis because it so happened that the usual polymerization of epoxides leads to hydroxy-terminated polymers; in other words, hydroxyls are the normal end-groups of these polymers. Uraneck et al., on the contrary, had to use special procedures to produce their telechelic polybutadienes since the usual polymerization techniques lead to polymers with inert or ill-defined end-groups. The authors also have the merit of having attracted attention to the importance of the functional end-groups by introducing a special name, which became more and more accepted as the need to designate terminally functional polymers increased.

The great interest in telechelic polymers resides in the fact that such polymers can be used, generally together with suitable linking agents, to carry out three important operations: (1) chain extension of short chains to long ones by means of bifunctional linking agents, (2) formation of networks by use of multifunctional linking agents, and (3) formation of (poly)block copolymers by combination of telechelics with different backbones. These concepts are of great industrial importance since they form the basis of the so-called “liquid polymer” technology exemplified by the “reaction injection molding” (RIM). Great interest has also been shown by the rubber industry because the formation of a rubber is based on network formation. In classical rubber technology, this is achieved by the cross-linking of long chains that show high viscosity. The classical rubber technology, therefore, requires an energy-intensive mixing operation. The use of liquid precursors, which can be end-linked to the desired network, offers not only processing advantages, but in some cases, also better properties of the end-product. Finally, the development of the “thermoplastic rubbers” (TPRs), which consist of ABA block copolymers or polyblock copolymers, in which A is a segment with high glass transition temperature (Tg) or melting point (Tm) and B a segment with low Tg, has furthermore stimulated the industrial interest in telechelic polymers, which are potential starting materials for such TPRs.

Although introduced in 1960, it took some years before the term “telechelic” became accepted in the literature, but in recent years, it appears frequently in the titles of articles and in the table of contents of books on polymer chemistry. The term appears regularly in the subject indexes of scientific journals such as Journal of Polymer Science, Macromolecules, Die Makromolekulare Chemie, and Polymer Journal. It is also mentioned in the keyword index of Chemical Abstracts single issues but not in the general subject index.

The original definition of telechelic polymer may need some comment or refinement. To start with, the term reactive functional group implies a reactivity toward another molecule, i.e., toward another functional group or a class of functional groups. It means that a polymer may be telechelic under certain conditions, but not telechelic under others. Theoretically, all polymers can be considered to be telechelic, provided one can find a reaction that is selective for the chain ends of the polymer, in other words, provided a given reagent is able to distinguish the end-groups from the main chain. Not only must the end-groups be reactive, they should react in such a way that a bond with another molecule is formed. This bond will mostly be a covalent bond, but also other (weaker) bonds such as coulombic bonds between charged end-groups (“halatotelechelic” polymers) or charge transfer complex-type bonds may be of great interest.

A second problem that is encountered when looking for a general definition and classification of telechelic polymers is the “functionality” of the telechelic. We have to make a distinction between the “telechelic functionality” and the functionality of the end-group itself. An important group of telechelic polymers have more than two reactive end-groups because they are branched or have a star-shaped structure. These polymers can be designated as tritelechelic, tetratelechelic, or polytelechelic.* Consequently, the “original” telechelics, having two reactive end-groups, are ditelechelics. Of course there is no reason to eliminate polymers that possess only one reactive functional end-group, and we will call these monotelechelic. (These polymers have sometimes been called “semitelechelic”, a term that makes sense only if the definition of telechelic is restricted to designate polymers with two reactive end-groups.)

II. FUNCTION

The functionality of the reactive end-group itself is another important parameter that will play a primordial role in the potential uses of the telechelic polymer. The usual telechelic polymers have monofunctional end-groups, i.e., end-groups that can form one bond with another functional group. Other end-groups may be unequivocally bifunctional or multifunctional. Such groups, if they can participate in a polymerization reaction, are of special importance because copolymerization of polymers containing such end-groups with low molecular weight monomers leads to graft copolymers (for monotelechelics) or to polymer networks (for di- or polytelechelics). Such telechelic polymers are “macromolecular monomers” and are commonly called macromonomers or macromers. Therefore, macromers have to be considered as a special class of telechelics, the classical macromer being bifunctional monotelechelic.

In defining the nature of a telechelic polymer, an important question is the following: can a polymer having different functional end-groups be regarded as telechelic polymer? Suppose we can make a linear polymer having one hydroxyl end-group and one amino end-group. Undoubtedly, this polymer would give a number of possibilities for constructing interesting well-defined polymer structures. The condition is, however, that all molecules have indeed one hydroxyl and one amino end-group. If only the average amount of hydroxyl and amino end-groups is one for each polymer molecule, it will not be possible to use this compound to produce well-defined structures, and we will not consider this as a telechelic polymer.

Keeping this in mind, the classical polycondensation polymers, obtained from two bifunctional monomers, cannot be regarded as telechelic, although they possess two functional end-groups, unless their synthesis has been conducted in such a way that the end-groups are the same for each individual polymer molecule present in the mixture. For example, a linear polyester having two hydroxyl end-groups or two carboxyl end-groups, is a telechelic polymer, but a linear polyester with a distribution of molecules having two hydroxyls, one hydroxyl and one carboxyl, and two carboxyls is not a telechelic polymer. On the other hand, a linear polyester in which all polymer molecules have one hydroxyl and one carboxyl end-group may again be considered as a telechelic. It will be monotelechelic for reactions involving either the hydroxyl or the carboxyl; it will be ditelechelic if it reacts at both extremities.

A very important requirement of telechelic polymers is their perfect terminal functionality, i.e., the number-average functionality of a ditelechelic polymer must be 2.0, that of a tritelechelic must be 3.0, etc. The main application of telechelics is the production of well-defined high molecular weight polymer structures such as graft polymers, (poly)block copolymers, and polymer networks by various end-linking reactions. End-linking being extremely sensitive to accurate end group stoichiometry, the end-products will be well-defined only if the functionality is a known whole number. For example, high quality networks can only be prepared by the use of prepolymers having a functionality of 2.0 or 3.0 or higher whole numbers. One of the great problems for the synthesis of telechelics is this requirement of perfect end-group functionality, especially when end-group transformations have to be carried out. A supplementary difficulty is the analysis to determine the end-group concentration within an acceptable experimental error.

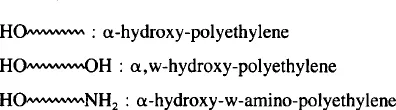

Finally, here are a few thoughts about nomenclature. The “α, ω-nomenclature” can be used for ditelechelic polymers (and also for monotelechelics). It uses the usual prefix substituent names for the functional end groups, followed by the name of the polymer. For example:

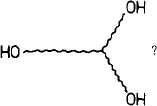

But, how to name a polymer as:

The Greek alphabet has only two extremities (α and ω), but this polymer has three! I propose the name “trihydroxytelechelic polyethylene”. This has the advantage that it can be used for polytelechelic polymers, also for those having different end-groups.

The “prefix-terminated” nomenclature or “prefix telechelic” such as “carboxy-terminated polyethylene” or “carboxytelechelic polyethylene” can be used to designate a class of polyethylenes having carboxylic end-groups, but the description is in fact incomplete because it does not say if it is a mono-, di-, or polytelechelic. To designate a particular polymer structure, it is better to use “a-carboxypolyethylene”, “γ, ω-dicarboxypolyethy-lene” or “tricarboxytelechelic polyethylene”.

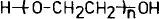

For complex end groups, the prefix name is put between brackets and preceded by mono-, bis-, or tris-; examples: γ, ω-bis(p-hydroxyphenyl)polyethylene. Another problem may arise if the polymer chain is unsymmetrical, as is the case for mono-substituted vinyl polymers and polymers containing hetero atoms in their chain. Let us take the example of polyoxyethylene (POE). The recurring constitutional unit of POE is -O-CH2-CH2-. If we consider a POE having two hydroxy end-groups, then we should, if we want to be rigorously correct, call this molecule a-hydrogen-ω-hydroxy-POE:

However, if we would call this a.w-dihydroxy POE, no sensible chemist would understand this to be a POE terminated at one end by an alcohol and at the other end by a hydroperoxide function. In fact, the second name is the commonly used one, and the first name would create confusion. As a conclusion, one can say that in the nomenclature the two important features of a telechelic must be clearly recognizable: the nature (and number) of the end-groups and the nature of the polymer backbone.

The flourishing of a field of scientific research depends on many factors, but two are preponderant: there must be a potential utility so that researchers feel that they are doing something useful, and reliable methods for doing the research must be available so that the researchers do not get frustrated. In the last 15 years, there have been tremendous advances in analytical methods available for characterization of polymers, more specifically the high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and gel permeation chromatography. Undoubtedly, the general availability of these methods has greatly contributed to the continuously increasing amount of research in the field of telechelics. On the other hand, more and more knowledge has been accumulated about the mechanisms of several polymerizations that made it possible to extend the number of polymers available in the form of telechelics.

It is the purpose of this book to assemble all this knowledge under the same cover.

REFERENCES

1 Uraneck, C. A., Hsieh, H. L., and Buck, O. G., J. Polym. Sci., 46, 535, 1960.

2 Bayer, O., Angew. Chem., 76, 553, 1947.

* The prefixes mono, di, tri, tetra, and poly are also derived from Greek.

Chapter 2

REACTIVE OLIGOMERS BY STEP-GROWTH POLYMERIZATION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. | Introduction | |

II. | Termination of an Oligocondensation Before Complete Conversion of the Functional Groups | |

III. | Use of the Stoichiometric Balance | |

A. | General Discussion | |

B. | Reactions Carried Out in Stoichiometric Conditions | |

C. | Reactions... | |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Introductory Remarks

- Chapter 2 Reactive Oligomers by Step-Growth Polymerization

- Chapter 3 Anjonically Prepared Telechelic Polymers

- Chapter 4 Telechelics by Free Radical Polymerization Reactions

- Chapter 5 Telechelics by Carbocationic Techniques

- Chapter 6 Telechelic Polymers by Ring-Opening Polymerization

- Chapter 7 Telechelics by Polymer Chain Scission Reactions

- Chapter 8 Macromonomers

- Chapter 9 Polyols for Polyurethane Production

- Chapter 10 Terminal Transformation of Telechelics

- Chapter 11 Halato-Telechelic Polymers: A New Class of Ionomers

- Chapter 12 Networks from Telechelic Polymers: Theory and Application to Polyurethanes

- Review Table

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Telechelic Polymers: Synthesis and Applications by Eric J. Goethals in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences physiques & Chimie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.