- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book examines the causes of the economic and political crisis in Argentina in 2001 and the process of strong economic recovery. It poses the question of how a country which defaulted on its external loans and was widely criticized by international observers could have succeeded in its growth and development despite this decision in 2002. It examines this process in terms of the impact of neo-liberal policies on the economy and the role of development strategy and the state in recovering from the crisis

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Argentina's Economic Growth and Recovery by Michael Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economia & Economia dello sviluppo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Emergence of Neo-Liberalism in Latin America

Situating the Argentine Experience

One of the central objectives of this book is to locate the Argentine experience within three broader theoretical and policy debates about the economic and social development process in developing countries. These debates concern the significance of the neo-liberal framework known as the Washington Consensus for economic management in Latin America, the role of state performance in the development process, and the role of institutional capacity as a critical component of state performance. This introductory chapter examines the first of these issues in order to frame the narrative and analysis that follows and also to distinguish the experience of Argentina in relation to other countries in the region and beyond. The debates about state performance and institutional capacity are presented in Chapter 2. As noted earlier, these three issues have proven to closely inter-connected.

Setting the Context of Economic History

The adoption of neo-liberal economic policies in Latin America during the 1990s can only be understood within the broader context of the often tumultuous history of economic and political change in Latin America during the twentieth century. This history is one of power struggles and conflicts between landed aristocracies and urban workers, middle classes and recent rural migrants, labor and capital, and state and civil society. The economic and social policies of individual countries reflect these struggles and also contribute to them. The region is the most unequal continent, with great differences between rich and poor, and the struggle for resources, opportunities, inclusion, and social mobility is a constant theme of this history. Neither the array nor relative power of these political forces remains static, so the history of the region is one of instability of policies and institutions. Ideas change and so does the capacity of institutions to implement them.

In 1998, the British economic historian, Rosemary Thorp, captured the changing and cyclical character of thinking about Latin American economies and development performance in the following observation:

Today’s conventional wisdom for Latin America heralds export-led economies fueled by technical innovation, but in 1900, the same idea was in vogue. The social cost of excluding poor and marginalized people is singled out as a crucial issue today, while only two generations ago exclusion was so thoroughly woven into the fabric of Latin America that it was simply accepted. The focus now is on the shortcomings of import substitution industrialization, in the process seemingly wanting to forget it was once reasonably considered to be the pillar of progress upon which a modern Latin America would be built.1

The adoption of a particular development strategy and set of policies, however, is not just an outcome of the evolution of changing circumstances, but also about the shifting theoretical ideas and framework supporting those strategies and policies including their origins, the experience of their application in other places, and how and through what channels do the ideas themselves travel and eventually are adopted. This chapter, therefore, seeks to explain the adoption, performance, and consequences of neo-liberal policies in light of the region’s economic and political history. These shifts in thinking can also be understood in terms of the broader historical changes and shifting pendulum of views about the relative primacy of the state and the market as explained by historian and philosopher Karl Polanyi.2

The understanding of this recent economic and political history is itself both enormously enriched and confused by the myriad interpretations of analysts, leading public figures, and the media, as well as by external observers and international institutions. Telling the story and identifying its implications for present policy and politics therefore is an enterprise with high stakes. Recently published books and institutional reports demonstrate that the debates about appropriate economic policies are hot, much contested, and actively present in current political struggles in many countries.3 The politics of the chosen historical narrative is present in the media on a daily basis.

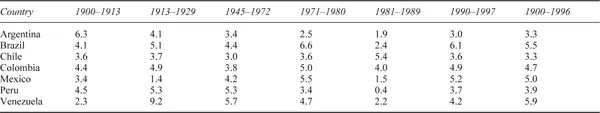

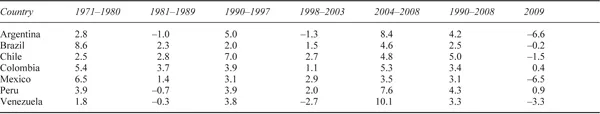

At the start of the twentieth century, Latin America had a population of 70 million people, 75 percent of whom lived in rural areas. By 2000, the population had reached 500 million, with 66 percent living in cities and towns. In 1900, some 75 percent were illiterate; by 2000, 87 percent were literate. Population growth accompanied massive economic growth as well. Tables 1.1 and 1.2 show the gross domestic product (GDP) growth for Latin American countries for different periods from 1900 to 2008 Despite this growth, at the beginning of the twentieth century, 40 percent of the Latin American population was poor.4

Table 1.1 Average GDP growth, 1900–1996

Source: Thorp, 1998. Progress, Poverty And Exclusion: An Economic History of Latin America in the 20th Century, p. 2.

Table 1.2 GDP growth, 1971–2009 annual rates of variation

Source: United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2010, Time for Equality, 2010, p. 53.

The first decades of the twentieth century saw rapid economic growth, fueled by trade, European immigration to Argentina and Brazil, and institutional development. Many countries celebrated the first 100 years of independence from Spain. The 1920s was a period of institutional innovation: central banks were created and customs and tax collection agencies established. It was a time of the consolidation of capital in industry and manufacturing, as well as by an urban middle class. This process varied across countries, but it created the basis of significant political struggle throughout the 1930s and through World War II.5 Twenty years later, new development institutions began to appear: planning ministries, development banks, and industrial development institutions. The first half of the twentieth century was also one of incorporating new economic and political forces into society, including labor, which became an increasingly important political force.

Unlike Europe and Asia, Latin America came through the 1939–1945 period without the physical and institutional destruction of its economies, but it did strongly feel the economic and political impact of the World Wars and the Great Depression, with a drop in demand for its exports, higher prices for its manufactured imports, and changing levels of protection of its trade. While there were differences in the position of Latin American countries towards the war against fascism, Latin American economies had continued to grow following the 1930s and the subsequent growth in global demand for goods, services, and raw materials, which accelerated after 1939.

Ideological conflict became important in the postwar period in many countries, with arguments about the role of the state, the need for land reform, and how to address the well-established differences in income and wealth between a landed upper class and rapidly growing middle and lower classes. Even though these historic debates predated the Cold War in countries such as Guatemala, Brazil, Chile, or Argentina, these economic issues quickly became politicized internally through the growing activity of groups across the ideological spectrum.6 They were also internationalized by the Cold War perception of the United States that more social and distributive views of economic policy would take Latin American countries towards socialism and the Soviet Union, thereby providing the justification for active intervention in all countries in the region.7

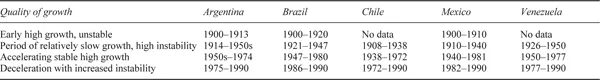

Taking a broad view, Latin American economies grew substantially but very unevenly during the first half of the twentieth century, with high levels of volatility depending heavily on the changing global economic environment. These twists and turns resulted in processes and patterns of growth that generated and exacerbated many conflicts and unresolved problems. A central and continuing question concerned the quality of economic growth itself and how its benefits were distributed. Indeed, the highly unequal pattern of economic growth from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the concentration of wealth and land in many countries had provided the foundation upon which export-led economies continued to grow, diversify, and consolidate during the twentieth century. This form of growth was built on monopolies and land ownership patterns inherited from the colonial period. Indeed, powerful landed elites were able to avoid paying taxes and thereby also limited the redistributive power of the state.8 This distribution of wealth and income also had a major impact on the evolving character of political systems in the region as rural elites struggled with urban middle classes for political power.9

The growth of Latin American economies, therefore, was not a smooth process. The region experienced extraordinary instability of prices and incomes over time, with major consequences for macro-economic performance and the welfare of national populations. While Latin American economies grew at over 4 percent through the twentieth century, they experienced intense periods of instability even before the debt crisis and post-1980, growth of the global economy.10 Some of this instability resulted from the weak performance of national financial systems, and later by the interaction of these institutions with global markets. There is an extensive literature on the economic instability of individual countries, particularly Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico, but other countries also experienced wide swings in their growth.11 This is well-illustrated in Table 1.3 on the levels of growth over various periods in the region.

Table 1.3 Phases of productivity growth, 1900–1990

Source: Thorp, op. cit., p. 16.

Postwar Economic Growth: 1950–1980

The post-World War II period saw a continuity with patterns in the 1930s as the state was expected to play a growing role in economic development and in protecting individual countries from the growing impact of the world economy. This led to the adoption of import substitution strategies in most countries, including the biggest economies: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico. These strategies were well articulated by Latin American economists such as Raul Prebisch, who argued in a 1951 report of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) that, “Two World Wars in a single generation and a great economic crisis between them have shown the Latin American countries their opportunities, clearly pointing the way to industrial activities.”12 Latin America could not depend on the stability of the global economy. Moreover, despite patterns of trade and foreign investment, the economic gains from technological innovation in the industrialized countries actually remained in those countries, while those gains at the periphery did not generate local benefits. He concluded that there was a need to actively promote local innovation and investment as central components of industrial development strategy and a means to substitute local production for imports, a strategy that became widely known as “import substitution.”13 Other leading Latin American economists such as Celso Furtado also supported this view. Their intention was to protect growing national industries from international competition in order to allow the growth of employment, productivity, and technology, and to keep incomes and profits within national economies. The period of 1945 to 1973 saw a growing role for the state in many Latin American economies in promoting industrialization.14

These policies we...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Prologue

- 1. The emergence of neo-liberalism in Latin America: situating the Argentine experience

- 2. State performance and institutional capacity in development

- 3. The Argentine crisis: what happened?

- 4. Stabilization in 2002: stopping the free fall into poverty

- 5. Electing a new government and facing the external world

- 6. Strengthening the state to manage at home

- 7. A new government to address the geographies of inequality

- 8. The politics of redistribution: the conflict with el campo

- 9. Urban inequality

- 10. From crisis management to sustainable development: extending the time horizon

- 11. Argentina’s experience and the search for alternatives

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index