- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geomorphology & Time

About this book

Time is a central feature of geomorphological research, and is used in this book (first published in 1977) to provide a conceptual framework within which to consider and compare old and new approaches to the field of geomorphology. The emphasis is on providing not merely a manual of current research but an introduction to isolate ideas and concepts, stimulate critical discussion and examine some of the problems that are involved in dealing with data.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

‘The leading idea which is present in all our researches, and which accompanies every fresh observation, the sound which to the ear of the student of Nature seems continually echoed from every part of her works, is —

Time!——— Time! ——— Time!’

George Poulett Thomson Scrope 1858

Time pervades all fields of geomorphology, from the most restricted observation of an obscure localized geomorphological process, for example the solution of minerals from potholes in glacially eroded granites, to the macroscopic, highly abstract modelling of drainage systems development over several thousands of years. Moreover, some of the most important geomorphological concepts, are time-centred — equilibrium and grade, magnitude and frequency, equifinality, denudation chronology, variance minimization and entropy maximization.

The various interests range over the finite span of time of which we have knowledge: the development of erosion surfaces across the Archean basements; the sequence of uplift and erosion in the late Tertiary; the chronology of glacial and deglacial stages in the Quaternary; the lateral translation of fluvial activity on the flood plain; the passage of a peak of sediment in the channel or the variations in stress on a sand particle in the turbulence of a laboratory flume.

The techniques we use to observe the phenomenon under investigation are conditioned by the time scale and time characteristics of the processes or forms which are deemed important. There is, for example, little place for continuous observation of snow cover in temperate latitudes; the spacing of observations on wave height must take into account the periodic nature of the phenomenon both in time and space, and similarly observations of mudflow activity at very long intervals yield cumulative results which are probably of very limited use in illuminating the principal factors generating and controlling the flow, especially if the response rate to the factors controlling the flow is rapid.

The centrality of time in geomorphology stems from three fundamental developments in the study of the subject. These are, in order of development, (i) denudation chronology and evolutionary studies, (ii) accurate description of the mechanism and rates of operation of geomorphic processes, (iii) the adoption of a systems-based attitude towards geomorphological investigations. It is ironic, but by no means fortuitous, that time — the central theme of denudation chronology — plays so important a role in the latter studies. It seems to make good sense to rearrange the order of these issues to represent increasing time spans, decreasing time precision and a logical change in the observation, model-building and model-testing techniques. We also choose to progress from scientifically general ideas about time and observation in time to those which are particularly ‘geomorphological’. The difficult subject of denudation chronology therefore comes late in our discussion. At the same time, it is not the purpose of this book to perpetuate the rather fruitless polarization of the subject between denudation chronology and contemporary processes studies, or between advocates of time dependency and time independency. Least of all are we able to differentiate between quantitative and non-quantitative. The problems of contemporary process studies are just as difficult as those of long-term evolution; the latter are just as capable of precise and systematic study and each should be complementary to the other.

This book is about one of the central issues of geomorphology, not the central issue. Lest it should be thought that it is exclusive, recall that other equally central issues exist — lithology and process, geomorphology and climate, spatial variability, or stochastic processes. All of these themes impinge on the problems of observation, model-building and interpretation of events, in time.

Geomorphological data and temporal explanation

Before discussing the more important ways in which geomorphologists are concerned with time, it is useful to summarize a few important aspects of time in terms of the nature of geomorphological data and the common modes of temporal explanation.

Data

Many of the problems described in this book will be concerned with the relationship between time and space, and it is therefore important to recognize that they do not always possess analogous properties. The fundamental temporal attribute of duration may be compared to the spatial qualities of area or distance in that they are of finite and of measurable magnitude. In terms of temporal or spatial relationships of phenomena, however, time is distinguished by possessing the property of intrinsic direction and in the macroscopic sense being irreversible. Thus we speak of past, present and future, of being and becoming. Events begin, endure and end and are fixed in position, and therefore direction, relative to preceding and succeeding events. There is a striking difference with spatial phenomena which must be fixed in space by reference to at least three points. This transitory, directed nature of time is fundamental to any understanding of process where we seek to establish the rate of operation, direction, duration, memory of preceding events or relaxation times.

Geomorphological data may be classified on a time basis for they may possess several distinctive properties. For example, discrete events may be regarded as ‘isolated’ if they occur so infrequently that they may be regarded as of ‘once only’ character. More commonly, they possess the properties of continuity, such as the temperature of a rock mass; fluctuation, as the temperature rises and falls, and sequential occurrence as a time-series. In such a sequence it is possible to recognize simple patterns which may be regular, random or clustered; short or long term trends such as evolution and succession; cycles, or intermittent sequences such as might occur in volcanic events or movements along a fault.

Geomorphological phenomena may be regarded as slowly changing or dynamic, if measured against the human time scale. Slowly changing phenomena include sea-level change, isostatic rebound and the ground loss implied in the ideas of peneplanation or pediplanation, though in practice such changes are difficult to observe. In these ideas the concept of movement is a lesser consideration than in phenomena that are regarded as dynamic.

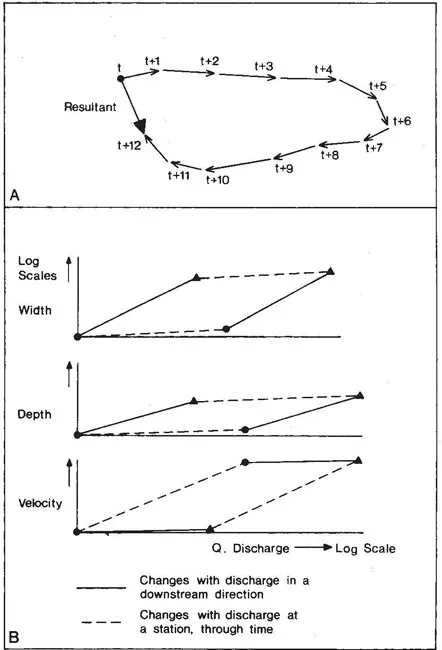

Velocity and acceleration are vital elements of geomorphological process studies. Velocity, expressed as the distance moved in unit time (L/T), is among the most common of all process measurements and is often combined with direction to yield vectors and resultants of position or system states (fig. 1.1a). The net direction and amount of sediment transport is a useful example. This also serves to illustrate the close relationships which exist between time and space, for we not only combine them to yield velocity (L/T) but we also compare the values in further time-space terms. Changes in stream velocity at one point in space (gauging station) or at several points in space (several gauges downstream) (fig. 1.1b) demonstrate the notion as do graphs of distance moved in unit time or studies of kinematic wave phenomena (Nye 1965).

Dynamic phenomena may also be regarded as random, unidirectional or cyclical in character. Interest in randomly-occurring phenomena is rapidly increasing as geomorphologists move away from deterministic to probabilistic modes of explanation. Recently, for example, Howard (1965) has suggested that landslides may be random events; Culling (1963) has attempted to develop a theory of soil creep based on a consideration of random forces in a soil mass. Most geomorphological phenomena, however, incorporate a strong unidirectional space-time element. Most commonly, this includes the influence of gravity which is the dominant force in all geomorphological processes. Cyclical characteristics often occur where climatic fluctuations are involved. The most notable examples come from fluvial geomorphology.

Finally, the results of geomorphological events may be regarded as reversible or irreversible. The former is implicit in ideas of steady state beach profiles where sediment is lost and returned. Total ground loss from a drainage basin or landslides from a cliff in the short term are examples of irreversible change of the landform geometry.

1.1 (a) Hypothetical resultant and vectors of net sediment transport in an estuary. Each arrow represents the successive paths of a particle. The resultant represents the net effect of these movements. (b) Relationships between channel discharge, velocity and geometry at a station through time and in a downstream direction.

Explanation

It is always difficult to remove elements of subjectivity from our view of time since we are influenced by our own experience of natural phenomena (Meyerhoff 1960). There are real dangers here in our attempts at temporal explanation, for as with any model the temporal model must be verified by empirical statements which may not fulfil our subjective ideas.

Perhaps it is not surprising that many attempts to explain geomorphological phenomena had a genetic and evolutionary bias closely related to the experience of man. Thus, for e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General editors’ preface

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The measurement of time

- 3 The measurement of variables in time

- 4 Analysis of temporal data

- 5 Rates of operation of geomorphological processes

- 6 Qualitative temporal models

- 7 Quantitative deterministic models of temporal change

- 8 Stochastic models of form evolution

- 9 Space and time

- Bibliography

- Appendix: The metric system: conversion factors and symbols

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Geomorphology & Time by J.B. Thornes,D. Brunsden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.