![]()

Chapter 1

Growing Up with the City

Perceptions of Place

Age is a lens through which both cities and the people who live within them are viewed. A city, of course, is seen to age at a far slower rate, and so it was that Melbourne, the settlement first established on the banks of the Yarra River during the winter of 1835, could still be described as young long after its founders had gone to their graves. In 1872, visiting English novelist Anthony Trollope observed Melbourne ‘in all the pride of youthful power … boasting to herself hourly that she is not as are other cities’.1 Similarly, historian Henry Gyles Turner, reflecting in verse on 50 years of urban expansion in the 1880s, recalled the early days of the ‘infant’ community, its subsequent ‘schoolboy growth, illformed but strong’, and a later ‘infusion of strong manhood’s prime’ with the onset of the gold rush.2 Melbourne’s maturation then slowed, Turner stated, with the city retaining as abiding characteristics ‘Youth, beauty, grace, radiance’ and a halo of ‘perennial brightness’.3

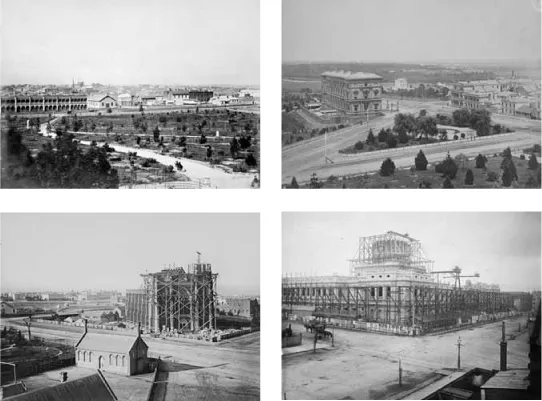

A refraction of that youthful glow is captured in photographs from the period. Compositions by Charles Nettleton, for example, document the freshness of city spaces dotted with saplings or newly planted shrubs and chart the construction of important civic institutions (see Figure 1.1). Nettleton, then approaching his 30th birthday, arrived in Victoria from northern England in 1854.4 By contrast with the heavily industrial cities of his youth, and by pointed comparison with ‘old London town’, Melbourne’s parklands, public buildings and general dynamism must have seemed both marvellous and modern in the decades after his arrival.5 In the sense of its perceived attractiveness, and also by virtue of incipience, sojourners and settlers like Trollope, Turner and Nettleton present an image of Melbourne as ‘becoming’. An air of imminence pervades their characterizations of the colonial capital.

Fig. 1.1 Becoming space: four views of emergent Melbourne. Clockwise from top left: Charles Nettleton, View from Observatory in Flagstaff Gardens (2) (albumen silver, 1866); Charles Nettleton, Elevated Views of Melbourne Buildings (albumen silver, c. 1870 [featuring the Treasury Building on Spring Street]); The Supreme Court During Construction, Showing Corner Little Bourke and William Streets, Melbourne (not attributed; albumen silver, c. 1875); Charles Nettleton, St. Patrick’s Cathedral (albumen silver, c. 1866). All four images courtesy Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

The depiction of Melbourne as a becoming city was double-edged, however. Rendering a city youthful implies promise and energy, but also suggests that it is a work in progress, prone to ‘growing pains’. Indeed, several writers of the period commented that Melbourne appeared ‘unfinished’ and that the city lacked the solidity of longer-settled Sydney.6 Gaps in the city grid troubled English journalist Richard Twopeny, for instance, who observed in 1883 that despite Melbourne’s overall ‘metropolitan’ feel a ‘rather higgledy-piggledy look’ remained, with the settlement ‘constantly outgrowing the majority of its buildings’ and featuring ‘gaps in the line of the streets’.7

Twopeny enjoyed a measure of critical distance in passing his judgements, posing as an outsider looking in, but his sentiments were not confined to visitors. The persistence with which new arrivals were cajoled into giving an opinion on the city (‘If I was asked once, I was asked twenty times what I thought of Melbourne before I had been twelve hours in it’, grumbled one newcomer in 18808) implies that at least some Melburnians also felt anxious about the processes of place-making, and required external validation for their city-building efforts. With rapid change all around, some commentators even harboured associated fears that the city was simply growing too fast for its own good. Seen from this perspective, rampant urban development was a curse and not a blessing, with the city’s chance of potential greatness jeopardized by relentless construction.9

Melbourne’s expansion was indeed striking: after more than an eightfold increase in the number of residents during the 1850s and 1860s (a surge associated with the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851), the population of Melbourne at the census in 1871 stood at 191,449. Ten years later, 262,389 people resided in the city, with a further 200,000 added in the go-ahead 1880s to produce a total of 474,440 at the 1891 count.10 At that time, an associated boom in property prices placed the city behind only London and Glasgow in terms of rateable value within the British Empire.11 Thereafter severe economic depression intervened and population growth ebbed,12 but the city was still pushing towards a total of nearly half a million inhabitants at the turn of the century.13 This rise to prominence positioned Melbourne at the forefront of the nineteenth-century ‘Anglo explosion’ identified by James Belich.14 A metropolis of international standing, Melbourne overshadowed similar settler cities like San Francisco, and many older conurbations, including São Paulo and Rome.

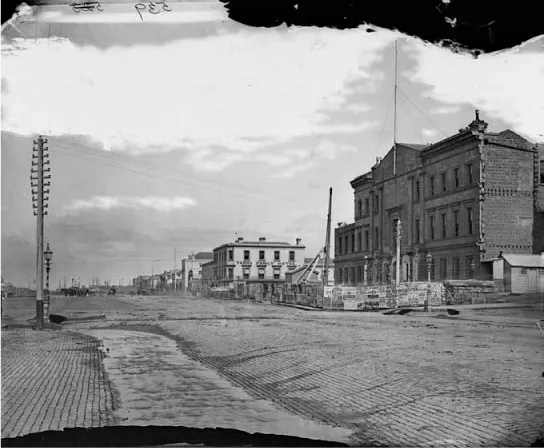

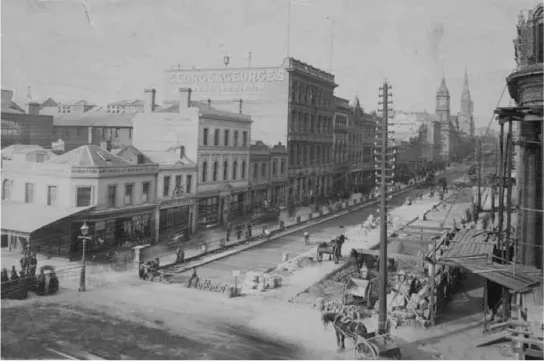

In this, the ‘upstart’ city,15 the provision of infrastructure could not initially keep pace with such population increases. Douglas Gane found Melbourne’s road surfaces ‘execrable’ in 1885, for example, noting in addition that open gutters were still being used to carry away excess water and effluent in the absence of adequate drainage and a sewerage system (Figure 1.2).16 A growth spurt in utility provision from the 1880s addressed some of these problems (see Figure 1.3), establishing extensive networks of public transport and gas provision (with the unintended effect that supply outstripped demand), and ensuring that by 1897 the city was at last satisfactorily sewered.17 But still the complaints continued. ‘No new city can dower its streets with the sentiment of historical associations’, wrote an irritated ‘Democritus’ in 1899, ‘but it should be able to better in material beauty and every day convenience the thoroughfares of cities that have been busy haunts of men for a thousand years.’18 At century’s end, Melbourne’s urban fabric seemed still to exemplify the awkwardness of adolescence.

The interplay between young Melbourne – in all its pride and with its various problems – and the young people growing up there in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is a central theme of this book. I argue that historical city space and the ‘space’ of life we refer to as youth merit study on their own terms, not merely to reveal antecedents for subsequent phases. Such study can deepen understanding of the temporally specific experiences of young people in urban settings and help us comprehend more fully the forces that have shaped the built environment. Expressed another way, there is an intrinsic value in regarding young people as young people, rather than as proto-adults, and the city of yesteryear – in this case Melbourne, one of Asa Briggs’s ‘Victorian Cities’ and a place sharing characteristics including rapid nineteenth-century expansion with many other settlements – in its own right.19 Thus the concern in this study is as much with being (that is, the historical moment or the experience of being young) as with the notion of becoming (historical processes or the journey through the life cycle).20 Of course factors of change, the currency of historical enquiry, cannot be forgotten. To this end, I regard the city as a process, or a series of spaces forever in the making, and similarly consider growing up as a process of perpetual evolution.21

Fig. 1.2 American & Australasian Photographic Company, Flinders Street West Showing Customs House Under Construction with Hoardings Covered in Theatre Posters; and Yarra Family Hotel, Melbourne (glass photonegative, c. 1870–75). Courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ON 4 Box 63 No 539

Fig. 1.3 View of Collins Street East, Melbourne, North Side (not attributed; albumen silver, December 1885). Photograph shows preparatory work for the laying of tram tracks. Courtesy Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria

This approach runs against the overwhelming trend in the colonial era to consider young people solely from the standpoint of their future prospects. It also calls into question current beliefs which demand metropolitan spaces be regulated by adults for the principal benefit of other adults.22 Nevertheless, to see age as a structural factor in society allows for alternative assessments to those yielded by analyses of class, ethnicity or gender, and for scholars of Melbourne to survey the urban scene from new perspectives. The remainder of this chapter dwells further on the link between the youthful city and its young people, broadening out to consider the demographic and discursive contexts within which the latter were situated.

Making Streets and Making Citizens

For any historian of youth and the city, to study coming of age in a location itself widely regarded as nascent is an enticing prospect. Although no previous histories have explicitly drawn together discussions about youth and the experiences of young people in this way,23 contemporaries in late-Victorian Melbourne did grasp the link between the circumstances of their city and the children in its midst. In August 1900, J. Hume Cook, Member of Parliament and prominent nativist,24 introduced a deputation t...