- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Jason Wood is Director of Heritage Consultancy Services, Lancaster, UK, and former Professor of Cultural Heritage at Leeds Metropolitan University, UK.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Amusement Park by Jason Wood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

p.29

Part I

Development of the amusement park in Britain

p.31

2 Mechanical pleasures

The appeal of British amusement parks, 1900–1914

Josephine Kane

In April 1908, the World’s Fair published an account of progress at the White City exhibition ground, which was nearing completion at London’s Shepherd’s Bush.1 Under the creative control of famed impresario Imre Kiralfy, a series of grand pavilions and landscaped grounds were underway, complete with what would become London’s first purpose-built amusement park.2 The amusements at White City had been conceived as a light-hearted sideline for visitors to the inaugural Franco–British Exhibition, but proved just as popular as the main exhibits. The spectacular rides towered over the whole site and were reproduced in countless postcards and souvenirs. Descriptions of the ‘mechanical marvels’ at the amusement park dominated coverage in the national press. The Times reported on the long queues for a turn on the Flip Flap – a gigantic steel ride that carried passengers back and forth in a 200-foot arch – and of the endless line of cars crawling to the top of the Spiral Railway before ‘roaring and rattling, round and round to the bottom’ (Figure 2.1).3 The Franco–British Exhibition was visited by 8 million people, but it was the amusement park that captured the public imagination and made a lasting impression.4

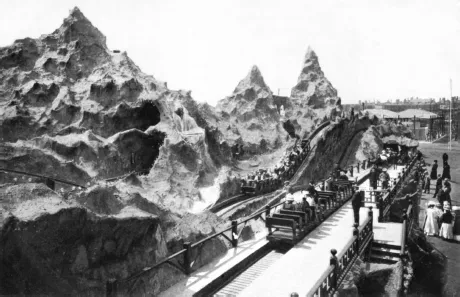

The following year, in a survey of London exhibitions, The Times acknowledged the growing importance of amusement areas, observing that: ‘We do not go to exhibitions for instruction . . . the great mass of people go to them for pure amusement’.5 The universal appeal of these amusements was deemed particularly noteworthy, and a remarkable royal endorsement in July 1909 provided definitive proof that the amusement park was not just for the masses. Queen Alexandra and Princess Victoria, visiting the Imperial International Exhibition at White City, were given a tour of the adjoining amusement park and – much to the delight of the crowds – decided to sample some of the rides. The Daily Telegraph reported that the Princess rode the Witching Waves (an early incarnation of the dodgems, recently imported from America), while the Queen herself took a trip on the Scenic Railway rollercoaster (Figure 2.2) and completed two winning runs on the Miniature Brooklands racetrack.6 It was a promotional masterstroke, signalling to the country that mechanised amusement had joined the ranks of respectable modern entertainments.

But Imre Kiralfy – the brains behind White City – was far from a solitary visionary. The Edwardian era produced a number of wealthy entrepreneurs who recognised the huge potential for amusement parks as new forms of commercial entertainment. In 1908, the amusement park concept had been around for about a decade, but was still really a novelty. Britain’s longest serving amusement park had started life on Blackpool’s South Shore in 1896, inspired by the success of New York’s iconic Coney Island.7 The Pleasure Beach, as it became known, cast the die for a growing number of competitors, and the opening of London’s White City coincides with the beginning of a frenzied phase of investment in American-style amusement parks in cities and seaside resorts across Britain. Between 1906 and 1914, more than thirty major parks operated around the country and, by the outbreak of the First World War, millions of people visited these sites each year.8

p.32

Figure 2.1 The Flip Flap and Spiral Railway at London’s White City, 1908

Source: © The author’s collection

p.33

Figure 2.2 The Scenic Railway at London’s White City, 1908. Built by John Henry Iles, this ride featured scale bridges, waterfalls and mountains and was famously patronised by Queen Alexandra in 1909. Note the group of smartly dressed women waiting a turn

Source: © The author’s collection

Kiralfy and his peers proclaimed themselves pioneers of modern entertainment. But did the experiences on offer really mark a significant break with the past? The early parks followed a distinct formula. Unlike their fairground cousins, amusement parks were enclosed, fixed-site installations controlled by a single business interest. In 1903, for example, William Bean and John Outhwaite secured a £30,000 mortgage to develop 30 acres of Blackpool’s shorefront into the Pleasure Beach.9 The target audience was urban, adult and socially all-encompassing. It ranged ‘from the young to the middle aged, and from those who could just afford an annual day trip, to the curious middle classes for whom the crowd itself was an essential part of the spectacle’.10 It is estimated, for example, that 200,000 people visited Blackpool Pleasure Beach on a typical bank holiday weekend in 1914.11

In the interests of minimising disreputable behaviour, wardens policed the grounds and, at night, flood lighting banished opportunities for shady dealings.12 They offered a wide range of popular entertainments, including battle re-enactments, cinema, dancing, theatres, concession stalls, landscaped gardens and often a zoo. But the amusement parks were dominated by machines for fun, and it was this aspect that marked them out as something unique. In particular, it was the rollercoaster – the defining symbol of the new parks – which enjoyed phenomenal success.13

Contemporary commentators were often bemused by the success of amusement parks. So, what exactly was their appeal? Why were the huge crowds – predominantly drawn from the wage-earning urban masses – prepared to pay for pleasure rides on machines that looked and sounded much like their everyday environment? The answer lies partly in the momentous cultural impact of industrialisation. The parks catered for the industrialised masses, offering – like the cinema – an otherworldly escape from the drudgery of industrial labour whilst (paradoxically) mirroring the factory system in their regularised opening times, dependence on modern transport networks and in the industrial rhythm of the attractions they offered. Just as concepts of work, time and space were altered by the onset of modernity, ideas about what constituted pleasurable experiences were transformed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For people living in towns and cities across Britain, visiting an amusement park forged new understandings of modern pleasure and became a defining counterpart to life in the modern metropolis. This chapter considers the significance of the amusement park experience for Edwardian Britons, focusing on the idea of ‘machines for fun’ and the crowd itself to explore their enormous appeal.

p.34

Machines for fun

The visual landscape of the Edwardian parks was quite unlike anything that had come before. Architectural eclecticism ruled. Amusement parks combined familiar styles – the exoticism and grandeur of international exhibitions and seaside piers, and the faux luxury and scenic realism of theatrical design – with the ‘tober’ layout of traditional fairgrounds.14 With a single sweep of the eye, the visitor might encounter the imposing industrial skeleton of a rollercoaster, a tin-roofed hoop-la stall, the towering concrete fortress of a battle re-enactment show, a mock-Tudor house and an Indian-style tea room (Figure 2.3). At the turn of the century, eclecticism was a source of delight, a visual pleasure learned at the exhibitions and transposed to the amusement world.15 But this seemingly ad hoc jumble was, in fact, underpinned by the visual language of machines. It was precisely this technological aesthetic – mechanical rides in motion and multicoloured electric lights – that set the amusement park experience apart.16 At sites such as London’s White City, the ‘gear and girder’ aesthetic of the industrialised workplace was transposed to the world of pleasure for the first time, and with great success.17 Indeed, the bare lattice-structures and whirling mechanical apparatus of the rides played a key role in the success of the amusement park formula.

The visual delight found in machines for pleasure clearly emerges from photographic evidence of early amusement parks. One particularly arresting image, reproduced on a souvenir postcard from Kiralfy’s Franco–British Exhibition of 1908, suggests the sense of pride and wonder associated with the latest thrill ride (Figure 2.1). In the foreground, smartly dressed men and women enjoy a sedate afternoon ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Amusement Park

- Heritage, Culture and Identity

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I Development of the Amusement Park in Britain

- PART II International Case Histories

- PART III Cultural Significance, Revival and Heritage Protection

- Select Bibliography

- Index