![]()

1 Psychoanalytic ecology and the uncanny

Sigmund Freud’s work on the uncanny, sublimation, symptom, mourning and melancholia is the basis for psychoanalytic ecology. For Freud, symptoms of psychopathology are inscribed on the surface of the patient’s, or analysand’s, body; for psychoanalytic ecology, symptoms of psychogeopathology are inscribed on the surface of the earth. Psychogeopathology is the mental illness associated with what Aldo Leopold (1991, pp. 212–217), a pioneer of conservation, called ‘land pathology.’ For Freud, symptoms of psychopathology are removed through the ‘talking cure’ that resolves the causes of the symptoms. Along similar lines, psychoanalytic ecology diagnoses the symptoms, and engages in a talking cure, of the psychogeopathology of the will to fill or drain wetlands, the uncanny place par excellence. The first chapter of Psychoanalytic Ecology draw on Freud’s work to discuss the psychodynamics of these processes.

Wetlands are sometimes not, and sometimes not ever, the most pleasant of places. In Western aesthetics they are not beautiful, sublime nor picturesque. They are anti-aesthetic, bodily, repressed and sublimated. Wetlands have been also associated with melancholia, or depression, especially ‘the slough of despond’ beginning with John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress first published in 1678 (Bunyan, 2008). Freud also associated melancholia with mourning as the loss of a loved object of love (Freud, 2005). Melancholia also involves a loss of the subject. Wetlands are a lost source of sustenance and entail a lost subject. The second chapter of Psychoanalytic Ecology draws on Freud’s work on mourning and melancholia to discuss the psychodynamics of love and loss of subjects and objects.

Alligators and crocodiles as monstrous creatures for Freud are vehicles and vectors for the uncanny. The uncanny urban underside is a fascinating and horrifying place for Freud. Freud’s work on the uncanny is drawn on more specifically in chapters 3 and 4 of Psychoanalytic Ecology. These two chapters diagnose the symptoms, and engage in a talking cure, of the psychogeopathology of demonizing and discriminating against these creatures and places. Placial discrimination and placism operate like racial discrimination and racism. Not only is there a hierarchy of places and races in which one race and place is privileged over all others, but also the ‘superior’ race figures the ‘inferior’ race and place in pejorative terms, for example, the slum as swamp (and vice versa), the ‘native’ as ‘primitive.’

The mining and pastoral (sheep- and cattle-grazing) industries exact oral and anal sadism against the earth. The work of Melanie Klein and Karl Abraham are used to diagnose the symptoms, and engage in a talking cure, of the psychogeopathology of oral and anal sadism in chapters 5 and 6 of Psychoanalytic Ecology. These chapters critique resource-exploitation, or greed and gluttony, and argue for a relationship of generosity for gratitude, of respect for, reciprocity with, and restoration of the earth to promote environ-mental health. Rather than just diagnose the symptoms and engage in a talking cure of them, psychoanalytic ecology nurtures environ-mental health and prevents the development and manifestation of the symptoms of psychogeopathology in the first place. The work of Margaret Mahler and Jessica Benjamin on psycho-symbiosis are used to do so in the final chapter. It also draws on the work of Lynn Margulis and Michel Serres on parasitism and symbiosis. Psycho-symbiosis is mental health associated with what Leopold (1999, p. 219; see also 1949, p. 221) called ‘land health.’ It nurtures living with the earth in the symbiocene, the hoped-for age superseding the Anthropocene.

The uncanny

The uncanny is the obverse of sublimation. Freud used the metaphor of sublimation drawn from chemistry to describe the process of sublimation by which sexual desire is displaced or deflected into ostensibly non-sexual realms, particularly the aesthetic and the intellectual (Freud, 1985a, pp. 39, 41, 45; see also Laplanche and Pontalis, 1973, pp. 431–434). The sublime and sublimation are closely linked as Immanuel Kant (1960, p. 57) attests that the sublimation of ‘subduing one’s passions through principles is sublime.’ The sublimation of sexuality into the aesthetic and intellectual are part of the condition of modernity, especially in the light of Simmel’s and Spengler’s argument that the intellect developed in conjunction with the rise of the modern metropolis (Simmel, 1950, pp. 409–424). Indeed, for Spengler (1932, p. 96; see also p. 92), ‘the city is intellect.’ The city, sublimation and the intellect come together in what Norman O. Brown (1959, pp. 281–283) calls ‘the city sublime,’ especially the modern city.

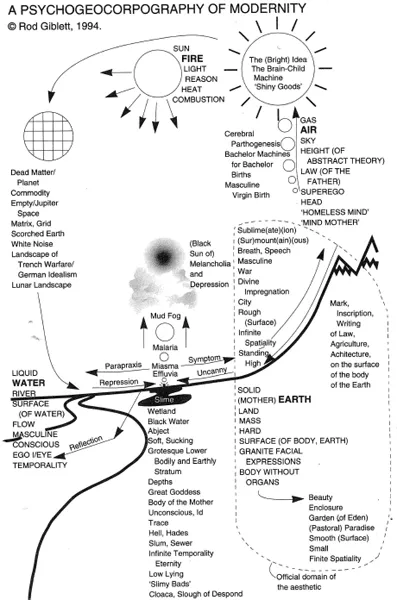

Yet, despite, or perhaps because of, the triumphs of modernity sublimation is always haunted by its shadow, its ‘other.’ The sublime, Zoë Sofoulis suggests, is always shadowed by the uncanny. Rather than the reverse of the sublime, for Sofoulis (1988, p. 12) ‘the uncanny is the obverse of the sublime, its other side: that from which it springs and that into which its turns,’ and even that into which it returns (Figure 1.1, p. 4 below). Sofoulis (1988, p. 15, n. 86) goes on to suggest that the uncanny is associated with slime, and that ‘slime is the secret of the sublime,’ which she encapsulates in the parenthetical portmanteau ‘s(ub)lime.’ The home, or perhaps more precisely the ‘unhome,’ of the slimy, and the uncanny, is the wetland summed up in the reference to ‘the slime of the swamplands’ (Tremayne, 1985, p. 150). The wetland is the uncanny place par excellence.

The concept/metaphor of the uncanny is arguably the greatest and most fruitful contribution of Freud to the study of culture and nature. Freud developed the uncanny in his essay of this title first published in 1919 in the psychoanalytic journal Imago. It was translated into English by Alix Strachey in 1925 for Freud’s Collected Papers. This translation was then ‘considerably modified’ for her husband’s James’s Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud and republished by Penguin in their ‘Penguin Freud Library’ sixty years later (Freud, 1985b). A new translation was commissioned and published by Penguin early this century (Freud, 2003).

Although a whole swag of Freud’s concepts and ideas (such as the Oedipus complex, penis envy, and so on) are critiqued and problematized, or pooh-poohed and dismissed as the years go on, the uncanny endures for a century as a useful tool in the toolbox of cultural criticism, literary theory, and political and philosophical critique. Freud (1919, p. 219; cf. 2003, p. 124) defines the uncanny as ‘that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.’ This is specifically, though Freud does not mention it, what Randolph (2001b, p. 97) calls ‘the mother-infant embrace,’ both in-utero and ex-utero. For Freud (1919, p. 244, 2003, p. 151) the uncanny is literally unheimlich, unhomely, but also homely, contradictory feelings which he found associated in the minds of adult males with female genitalia and in his own mind with the first home of individual human life in the mother’s womb. The uncanny entails a return of the repressed.

The return of the repressed occurs here and elsewhere for Freud as he does not refer to the mother – his or anybody else’s – or to her body, or specifically her womb. The maternal body is repressed in and by Freud in his essay on the uncanny as Randolph (2001a, p. 184, 2001b, p. 97) points out. The maternal body is repressed in and by patriarchal Western culture more generally (Giblet 1996, p. 6). Freud’s uncanny is uncanny in which the repressed maternal body returns. Freud (2003, p. 151) relates that ‘it often happens that neurotic men state that to them there is something uncanny about the female genital organs. But what they find uncanny [“unhomely”] is actually the entrance to man’s old “home,” the place where everyone once lived.’ Freud is, of course, referring to the womb, but seems a bit squeamish about doing so explicitly. ‘Man’s’ old home is the womb, whereas the old men’s home is (the entrance to) the tomb. The womb is more than a place (where action occurs, or a site where action takes place; it is not a passive receptacle). It is where the processes of life begin and are nurtured. It is also where the first bond occurs in-utero and the mother’s body is where the first bond occurs ex-utero.

Figure 1.1 A pyschogeocorpography of modernity

Life in-utero is a time and space when, as Freud (1919, p. 235; cf. 2003, p. 143) describes it euphemistically, ‘the ego had not yet marked itself off sharply from the external world and from other people.’ Freud (1919, p. 235) goes on to remark that ‘these factors are partly responsible for the impression of uncanniness.’ Both Freud’s euphemisms of ‘the external world’ and ‘other people’ for the mother’s body are factors partly responsible for the impression of uncanniness in Freud’s essay on the uncanny. Life in-utero and ex-utero is a time and space when the ego had not set itself against anything, including the external world, and from other people, such as the mother. The mother herself, as Randolph (2001b, p. 98) puts it following Klein, is ‘the infant’s “external world”’ and the ‘other people’ Freud vaguely refers to is the mother. The ego was a part and parcel of the inside world in-utero and the uncanny other, the mother, and of the outside world ex-utero. In 1919 in ‘The Uncanny’ Freud misses ‘the whole point about mothering’ as Randolph (2001a, p. 186) puts it. Twenty years later in his London notes of 1938 Freud (1975, p. 299) gets closer to the point about mothering by mimicking the child: ‘the breast is a part of me, I am the breast.’ All objects are initially conflated with one another and equated with the mother, or parts of her, especially her breasts, as she/they are the primary object for the young infant. Klein, as Randolph (2001b, p. 98) puts it, ‘gave the mother her due,’ as Mahler did too in her work on psycho-symbiosis and Jessica Benjamin in her work on ‘the bonds of love’ (and discussed in the final chapter of Psychoanalytic Ecology).

The home place and processes, or perhaps more precisely the ‘unhome,’ of the uncanny is not only the mother’s womb, but also the wetland, the first home of life on the planet in the earth’s womb and tomb from both of which new life springs and is nurtured (see Giblett, 1996, chapter 2; 2018, chapter 1). Wetlands are vital for life on earth, including human and non-human life. The leading intergovernmental agency on wetlands states that:

they are among the world’s most productive environments; cradles of biological diversity that provide the water and productivity upon which countless species of plants and animals depend for survival. Wetlands are indispensable for the countless benefits or “ecosystem services” that they provide humanity, ranging from freshwater supply, food and building materials, and biodiversity, to flood control, groundwater recharge, and climate change mitigation. Yet study after study demonstrates that wetland area[s] and [their] quality continue to decline in most regions of the world. As a result, the ecosystem services that wetlands provide to people are compromised.

(Ramsar Convention Bureau, online)

Yet more than the mere providers of ‘ecosystem services,’ wetlands are habitats for plants and animals, and homes for people.

The wetland is the uncanny place and process par excellence. It is also the home, or unhome, of alligators and crocodiles, the ‘king’ of the tropical wetland, the obverse of the temperate dry land, and the archetypal swamp monsters par excellence (discussed in chapter 3 of Psychoanalytic Ecology). In his 1919 essay on the uncanny Freud relates how:

I read a story about a young married couple who move into a furnished house in which there is a curiously shaped table with carvings of crocodiles on it. Towards evening an intolerable and very specific smell begins to pervade the house; they stumble over something in the dark; they seem to see a vague form gliding over the stairs – in short we are given to understand that the presence of the table causes ghostly crocodiles to haunt the place, or that the wooden monsters come to life in the dark, or something of that sort.

(Freud, 1985b, p. 367)

Freud’s account of the uncanny is crucial for a number of points. In the story the uncanny is produced by the smell of virtual crocodiles, the ‘king’ of the tropical wetland, the obverse of the temperate dry land, and the archetypal swamp monster par excellence as well as for John Ruskin ‘slime-begotten’ (as cited in the Oxford English Dictionary entry under ‘slime’). The crocodile is not the only creature slime-begotten. Slime is, as Camille Paglia (1991, p. 11) puts it, also for humans ‘our site of biologic origins.’ The story is also significant because of its emphasis on the sense of smell. It is no surprise then to find that Hoffmann (1982, p. 88), that master of the uncanny for Freud, in ‘The Sandman,’ the story in which Freud found the uncanny most powerfully evoked, should also refer to ‘a subtle, strange-smelling vapour … spreading through the house.’ For Freud the uncanny is unheimlich, unhomely, but also homely, contradictory feelings which Freud found associated with the first home of the womb in the minds of adult males.

The uncanny counters the aesthetics of sight and hearing of the sublime, the picturesque (pleasing prospects) and the beautiful. The uncanny as an aesthetics of smell is a kind of anti- or counter-aesthetics, especially to the sublime, which disrupts phallocentric sexual difference and its privileging of sight as the smell of the uncanny can be and has been strongly associated with female sexuality (Gallop, 1982, p. 27). The uncanny is associated with smell, but not just with any smell. The smell which evokes the uncanny is what Freud calls ‘a very specific smell’ which emanates from the virtual crocodiles but is not closely associated with them. This smell which Freud does not name (and hence represses as he does generally with the sense of smell by relegating references to it to what Gallop (1982, p. 28) calls his ‘smelly footnotes’ (Freud, 1985a, p. 288, n. 1, p. 295, n. 3) could be associated, given the lack of a discriminating aesthetics of smell, in the patriarchal mind, or to its nose, with the odour of female genitalia, which for Freud were the ultimate unheimlich, the (un)homely or uncanny.

This uncanny odour is, however, not the passive reverse of the sublime sight, but its active obverse, a kind of anti- or de-sublimation. The odour of female genitalia, the ‘odour di femina,’ Gallop (1982, p. 27) argues, ‘becomes odious, nauseous, because it threatens to undo the achievements of repression and sublimation, threatens to return the subject to the powerlessness, intensity and anxiety of an immediate, unmediated connection with the body of the mother,’ and with ‘Mother Earth,’ I would add, and with those regions with similarly offensive odours to the patriarchal nose, such as swamps.

The uncanny smell of the wetland entails a return to the repressed, as do uncanny smells in general (see Figure 1.1, p. 4). This return is associated by Freud with the artefacts of colonialism which bear the traces of other, al...