- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foods

About this book

What is food? This volume, written by a doctor, contains all the ways in which the question might be answered. First published in 1883, and reissued because there is nothing quite like it today, this unique study was undertaken at a time when foreign produce and new foods were becoming more widely available, and rising living standards were making familiar foods more accessible to all, prompting an interest in their origins and their nutritive qualities as revealed by scientific research into their chemical composition, preparation and physiological effects.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I.

_____

SOLID FOODS.

_______

SECTION I. — ANIMAL FOOD.

a. Nitrogenous

__________

CHAPTER I.

DESCRIPTION AND COOKING OF FLESH.

THE qualities by which foods may be classified have been already shown to be numerous and open to the selection of the enquirer ; but as it is not desirable in a work of this kind to attempt too much refinement of mere outline, we will omit two subjects, and refer the classification on the grounds of economy and chemical action to the work on Dietaries, whilst here we make use of the familiar but comprehensive one of solids, liquids, and gases. Solids will be divided into animal and vegetable, and each subdivided into nitrogenous and non-nitrogenous. We shall proceed first to treat of solid animal foods.

This important series of food might be subdivided into two other classes, viz., those which constitute the substance of an animal and are obtained when it is dead, and those which are the natural product of the animal and are obtained whilst it lives. The former includes the flesh, and as it varies in different classes of creatures, it is popularly subdivided into flesh, fish, and fowl, whilst the latter are milk, eggs, and other products. Those who profess to be vegetarians eat the latter only. It is also divided into lean and fat, both of which abound in animals generally, and this leads to a yet more technical division, viz. into nitrogenous and non-nitrogenous foods, since all lean flesh contains nitrogen, whilst all fats when pure are destitute of it.

Hence, however differing in appearance, ail kinds of flesh have certain nutritive qualities in common ; but the proportion in which the qualities exist varies, and each large division of the class has its own nutritive value.

The anatomical composition of flesh is very similar in every kind of creature, whether it be the muscle of the ox or of the fly; that is to say, there are certain tubes which are filled with minute parts or elements, and the adhesion of the tubes together makes up the substance of the flesh. This may be represented grossly by imagining the finger of a glove, to be called the sarcolemma, and so small as not to be apparent to the naked eye, but filled with nuclei and the juices peculiar to each animal. Hundreds of such fingers attached together would represent a bundle of muscular fibres. The tubes are of fine tissue, but are tolerably permanent ; whilst the contents are in direct communication with the circulating blood and pursue an incessant course of chemical change and physical renewal. The quality of meat consists in the character of the pulp or enclosed substance, whilst the toughness depends chiefly upon the tubes and the structures which bind them and other parts together, and both vary with the age and breeding of the animal. The aim in modern breeding is to produce the greatest amount of muscle and fat at the earliest period of life, but it is well known that whilst delicacy of flavour may thus be obtained, fulness and richness can be produced by age only. It is well known also that the connecting tissue, or the substance which binds the parts together, is relatively more abundant in ill-fed, ill-bred, and old animals than in the opposite conditions, and renders the meat tough. Hence it will be readily inferred that young and quickly fed animals have more water and fat in their flesh, whilst older and well-fed animals have flesh of a firmer touch and fuller flavour, and are richer in nitrogen. The former may be the more delicate, the latter will be the more nutritious.

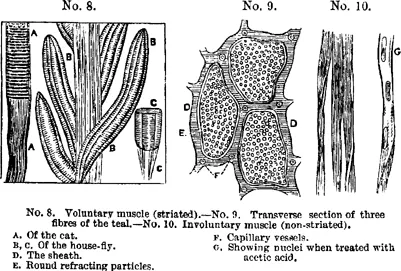

There are, however, two divisions of flesh which must be referred to, for although not differing much in chemical composition, they vary in their value as nutrients. The fibres of flesh generally are crossed by lines invisible to the naked eye, so that all voluntary

muscles are striated (fig. 8) ; but the other muscular organs which do not move by volition have muscular fibres which are not striated (No. 10), and are termed involuntary muscles. The heart is peculiar, being an involuntary muscle, but with striated fibres. The involuntary muscles are softer in their texture than ordinary flesh, but are not easily masticated ; so that, notwithstanding their identity in nutritive elements, they are not so nutritious as ordinary flesh, and never obtain so high a price in the market.

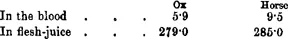

The juice of flesh has an acid reaction, and is more abundant in striated than in plain muscular fibre. It contains albumen, casein, creatine, Creatinine, sarcine, lactic acid, inosic acid, and several volatile acids, including formic, acetic and butyric acids, a red pigment similar to the colouring matter of the blood, and inorganic salts, chiefly alkaline chlorides and phosphates. It is much richer in potash than soda, as shown by the following comparison with 100 parts of soda in flesh-juice and blood (Liebig) :—

No. 11

It is said by the hunters in southern latitudes that flesh is the most tender and juicy if eaten directly after the animal has been killed, and whilst it is yet soft— nay, even when the animal is alive ; but if the stiffening of the flesh, called rigor mortis, have begun, it remains less tender until the rigidity has passed away and the changes of early decomposition have set in. Meat is always eaten in hot climates in its first or second state, unless means be taken to preserve it, since decomposition sets in too rapidly to allow it to be safely kept fresh for more than a few hours. On the other hand, flesh is never eaten in colder climates before the second state, and in order to lessen the hardness or toughness of it, it is usual to allow it to enter the third state, when it becomes soft and tender, and has gained a flavour from decomposition which is often approved. The nutritious elements, speaking generally, are the same in each state until the effects of decomposition appear, but the nutritive qualities, being dependent upon the power to masticate and digest the flesh, may be really less in the second than in either of the other states.

The desired effect may be produced at any stage in a rough manner by cutting the flesh into slices and beating it across the cut ends until the fibres are broken and the connecting tissues forced asunder ; but to effect this the slices must be thin.

The effect of cooking flesh is chiefly physical, and is chemical in a very limited sense only. When meat is either roasted or boiled, it decreases in bulk and weight, and the cooked food is generally less soft than fresh meat in the first state. The diminution in bulk and weight is owing to the extraction of the juices of so much of the mass of flesh as may have been acted upon by the heat, and these are chiefly water containing salts, and the peculiar flavour of meat, with a proportion of fat in a fluid state, gelatin, and perhaps some albumen. The flesh thus treated becomes contracted in bulk, from loss of the juices and by coagulation of the albumen, whilst the mass is composed of solid fibrin, with a proportion of albumen, and the juices and fat which have not been extracted. The tubes having lost much of their contents, shrink and separate from each other, and so far the meat may be made more tender ; but this varies in degree, and is often more than counterbalanced by the hardening of the albuminous contents of the tubes.

The object of cooking is to render the flesh more submissive to mastication and digestion, but it may be entirely frustrated if the substance of the flesh be hardened in any appreciable degree. It is also em-ployed to make the food hot when it is eaten with a view to improve its flavour, and to stimulate the sense of taste. It is only an incident in cooking, however inseparable from the act, that the flesh should diminish in weight by the loss of its fluid parts, but if all that is valuable from the extracted matter be collected, there will be no real loss of nutriment. There is, however, in this respect some difference according to the mode of cooking. If the meat be boiled, the introduction of fluid into the substance of the meat, whether between the structures or within the fibres, aids the extractive process, but at the same time retains and preserves that which is extracted. If it be roasted whilst surrounded on all sides by the air, the heat is not applied so uniformly and gently, and therefore the outside becomes overcooked before the inside is sufficiently cooked, and this occurs to a far greater extent than with boiling. Hence not only is the fluid part of the juices extracted and lost, but the loss is greater than when the meat is boiled. It is, however, to be understood that the matters extracted are only such as may be dispersed by heat ; and whilst, therefore, the evaporated water may carry off some of the flavours of the meat, it does not remove the salts which are present in the juices. Hence meat which is properly roasted has lost weight more than that which is boiled ; but if no account be taken of the matters extracted, it contains a larger proportion of nutritive elements than the larger mass of boiled meat, and in a given weight is more nutritious. When, however, the extracted matter is collected and used, there is a greater proportion of nutriment in the boiled meat with the broth than in the roast meat with the liquefied fat, and it is clearly desirable that both the broth and the boiled meat should be eaten together.

Stewed meat occupies a position between that of boiled and roast, for it may have been submitted to a greater heat and for a longer period than boiled meat, and thereby a larger proportion of soluble matter may have been extracted, whilst it differs from roasted meat in that the outside is not hardened and all the extracted material is retained. Boiled meat may be cooked so that the solid part shall still retain nearly all the nutritive elements of flesh, whilst the solid part of the stewed meat may be even less nutritious than the material which has been extracted from it.

The degree in which extraction of the juices takes place in cooking meat depends upon the heat employed, so that the proper application of heat is a fundamental question in cookery. It has been intimated that the extraction of the juices is chiefly from the cut ends of the soft fibres, and that the fibres become harder by the coagulation of the albumen during the process of cooking. When, therefore, the fibres have become hardened, they have lost some of their contents, but this condition prevents or retards the further passage of juices from parts beyond the hardened ends. The sooner, therefore, the hardening process can be effected, the sooner will the loss of juices be diminished or prevented. Dipping the meat to be boiled into boiling water effects this object, for albumen coagulates at a temperature much below that of the boiling point of water ; and placing the meat to be roasted very near the fire at first has the same effect. Thus less juices escape (all other parts of the process being equal), and the mass of flesh retains its nutritive elements. This is clearly desirable when the flesh only is to be consumed ; but if it be desired to make good broth or beef tea, the opposite course must be adopted, and by keeping the temperature below 160° the tubes may be emptied to a far greater degree than with a higher temperature. Hence the explanation of the saying, that you cannot have good broth and good meat from the same piece of flesh.

But the preliminary point having been settled, the proper mode of cooking is clearly not to coagulate the albumen unduly, but to make the whole mass of meat soft and tender. A slow fire, or water at a temperature of 160°, will suffice to expand the fibres, and in some degree to rupture them, whilst it separates these and other structures and renders the whole mass more fitted for mastication and digestion. To keep meat in boiling water, or to expose the joint to continued heat before the fire, is to make it hard and to extract a greater proportion of the juices.

Mesh thus treated is less susceptible of decomposition than fresh meat, by reason of its harder crust and the diminution of its juices, and may thus be pre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- PREFACE

- CONTENTS

- LIST OF RECIPES OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY

- LIST OF DIAGRAMS, WOODCUTS, AND TABLES

- INTRODUCTORY :—THE NATURE AND QUALITIES OF, AND THE NECESSITY FOR, FOODS

- PART I. SOLID FOODS.

- PART II. LIQUIDS.

- PART III. GASEOUS FOODS.

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Foods by Edward Smith,Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.