- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Public Library in the Bibliographic Network

About this book

This book, first published in 1986, focuses on valuable information to all public library professionals who have questions about their participation in bibliographic networks. Contributors provide insights into both the benefits and the costs of networking by libraries of varying sizes and geographic locations. The actual uses of networks, their costs (including initial and ongoing expenses), and staffing needs are clearly explained.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Public Library in the Bibliographic Network by Betty Turock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Lingue e linguistica & Scienze dell'informazione e biblioteconomia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Cost and Benefits of OCLC Use in Small and Medium Size Public Libraries

Linda G. Bills

From January of 1980 to December of 1982, the Illinois Valley Library System (IVLS) and its participating libraries conducted an LSCA funded experimental project in OCLC use. Although the purpose of the project was to examine the costs and benefits of OCLC in small and medium size libraries of all types, 20 of the 33 participants were public libraries. During the project both subjective and objective studies were conducted to measure OCLC use and its effects on the libraries and the System. This article summarizes those studies. Complete documentation is available in a series of reports from the Illinois State Library (Bills, 1982–1984).

THE SYSTEM AND THE LIBRARIES

The Illinois Valley Library System is one of eighteen state funded agencies in Illinois whose purpose is to provide services to their participating libraries and to promote cooperation among them. IVLS is a multitype which currently has 73 participating libraries, 35 of which are public. It includes a large urban center (Peoria), suburban areas, and rural farming/industrial communities.

The System’s relationship with its participating libraries can best be explained by it role statement:

The role of the Illinois Valley Library System shall be to help existing libraries reach their full potential by facilitating cooperative activities between libraries and by providing services that cannot be provided through maximum local effort.

Linda G. Bills, OCLC Project Director, Illinois Valley Library System, Pekin, IL 61554.

The project described was funded by an LSCA grant under the auspices of the Illinois State Library. The article is based on a series of reports published by the Illinois State Library.

The System supplies delivery among libraries, interlibrary loan, back-up reference, films and talking books, among other services. A staff of professional librarians, employed by the System, serve as consultants. Participant libraries agree to share resources according to the Illinois Interlibrary Loan Code, to meet the primary needs of their own clientele and to maintain the level of library support that existed at the time they joined the System. In addition, all public libraries are required to participate in reciprocal borrowing.

THE OCLC EXPERIMENTAL PROJECT

In 1977, a special Task Force at IVLS searched the literature to determine the costs and benefits of various alternative proposals for automated resource sharing. This search revealed a dearth of information. What was available dealt almost exclusively with larger units of service, especially research libraries and large academic institutions.

The Task Force recommended, therefore, that a project be undertaken as an experiment to use OCLC for local resource sharing among small units of service. An LSCA grant designed to do this was funded by the Illinois State Library. The focus of the project was to provide increased access to resources by building a data base of local holdings that could be shared among area libraries as well as with libraries throughout Illinois and the nation. The use of OCLC as a cataloging tool was a complementary process whose costs and benefits were also examined.

PROJECT STRATEGIES

During the project, staff of small and medium size libraries used OCLC terminals located either in their own library or in a neighboring library. Host libraries were those which had terminals and printers throughout the project. Guest libraries had no permanent terminal or printer, but used one in a host library. Together a host and its guests formed a cluster. Each library had its own profile and OCLC symbol. The staff were trained in the use of both the cataloging and the interlibrary loan subsystems of OCLC. Other subsystems, such as acquisitions and serials control, were not introduced as part of the project.

The grant reduced the financial burden to the libraries participating in this experiment. All OCLC equipment and use charges were subsidized for two years. The only payment most libraries made was a per title refund to the project of the amount it cost to catalog before OCLC was in place. Interlibrary loan charges, retrospective conversion, profiling, terminal maintenance, service fees and installation were paid for by the project.

In order to build an online database of local holding symbols in OCLC, every participating library was required to update records to reflect all the books they owned which were published in 1975 or later. Staff time and travel required to do this work were not reimbursed to the library; it constituted part of their local effort. Some of the libraries, in addition to what was required, converted earlier titles or included audiovisual materials and sound recordings. Work in retrospective conversion began in December of 1980. Most of it was completed by December of the next year. During the project, in addition to the fixed terminals, six were shifted among most of the project libraries so each could have a terminal available for patron use for six months. These public access arrangements were intended to increase patron awareness of OCLC and library networks.

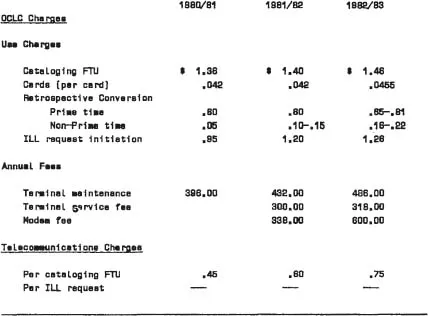

OCLC Costs. The prices charged for OCLC services vary from network to network. The ILLINET network office is totally supported by the Illinois State Library, so none of the costs for its staff, equipment or other expenses fall on the membership. There are no network, entrance fees or membership fees. As a result, through ILLINET members paid the OCLC charges plus a share of the telecommunications costs for the Illinois OCLC network. Table I summarizes the cost of OCLC use on a dedicated line during the project.

The acronym FTU means first time use, the basic cataloging fee charged by OCLC the first time a library uses a record; there is no charge for later uses. ILLINET did not begin charging a modem fee until March, 1982. It was pro-rated for previous months from July, 1981 to cover existing telecommunications’ bills. Until July, 1984 ILLINET distributed telecommunications costs based on OCLC use.

In addition, each library had certain start up expenses which included, at the time of the project:

| Terminal purchase | $3,700 |

| Modem installation | 148 |

| Installation of electrical | |

| outlets | Varied |

| Profile costs | Varied |

TABLE I

COSTS OF DCLC USE IN ILLINET

Dedicated Terminal

Dedicated Terminal

The strategy was to relieve libraries of nearly all these expenses and let them experience OCLC use without having to commit funds. At the end of the project, when they were asked whether they would keep or drop OCLC, it was hoped that their decisions would be based on their experiences in the previous two years rather than on any large, past financial investment.

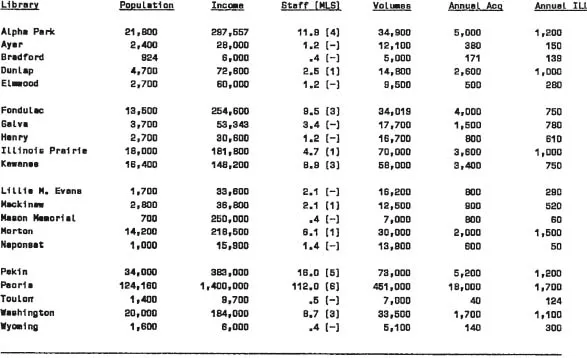

Project Libraries. When financial support ended in June of 1982, each participant had to decide whether to maintain the OCLC connection at its own expense. Twelve of the 20 decided to do so. The public libraries in the project ranged considerably in size and circumstances. The largest, the Peoria Public Library, serves a population of 126,000 and has four branches besides its large downtown facility. The smallest, Mason Memorial Library in Buda, serves a rural town of 700. Table II gives a few statistics for these libraries.

Staff size is given in full time equivalents (FTEs), with the number of staff members having MLS degrees shown in parentheses. Annual acquisitions are based on 1982 figures. Annual ILL is for 1980, before extensive use of the OCLC subsystem.

The experience of the libraries’ staffs varied greatly. In one case the librarian had worked in a pre-professional capacity as an OCLC copy cataloger. In a few others the director and/or some staff members had recently taken courses that included an introduction to OCLC and MARC. One of the participating libraries had used OCLC for interlibrary loan as part of the nationwide test of that subsystem, but had never used it for cataloging. In the larger libraries, several directors had investigated OCLC as a potential tool from the administrative point of view. Overall, however, the level of hands-on experience by directors and staff was low; most had never been exposed to OCLC or automated systems of any kind. Their understanding of the way OCLC functioned, what it would do for their libraries, and how it might affect their operations was based on information received from the ILVS. In many cases, their agreement to participate was an act of faith in response to the System’s recommendation.

In the majority of the project public libraries, staff were not only unfamiliar with automation, they also were not aware of many facets of cataloging that are central to understanding MARC tagging and using OCLC records. Cards for their catalogs were obtained from vendors or typed in-house. If CIP was available, it was used with very little alteration. The most frequent changes were in class numbers or subject heading to conform with the existing catalog.

Expectations. During interviews in May of 1981, librarians were asked to describe what their expectations for the project were. Their responses generally fell into two groups—professional and personal. The major professional, or library-oriented, expectations were the anticipation of new/enhanced user services and concern for how OCLC could be supported after the project. The more personal anticipations highlighted some of the problems on introducing OCLC to librarians with no previous experience. They included:

TABLE II

Public Library Full Participants in the OCLC Project

Anxiety about whether they could handle the technology and learn the necessary skills.

Concern about staff resistance to the changes and how the staff would adapt.

Concern for the management, safety and housing of the equipment.

The anxiety over handling new technology focused on the anticipation of personal inadequacy because of inexperience rather than fear of dehumanizing influences. Only five directors said that they knew what to expect because of previous experience.

Profiling. New OCLC members must create a profile which describes the format and print characteristics of their catalog cards. In some networks this is mediated by network staff who help the library fill out the necessary technical forms. In the project, it was mediated by system staff who, in turn, were helped by ILLINET. Each library had its own profile so that each library would have its own OCLC library symbol. Public library profiles were particularly complex when compared to academic libraries, for example, because holdings were broken into collections and subcollections such as juvenile, easy, picture books, young adult, mystery, large print, etc.

The chief difficulty with the original profiling was the lack of familiarity in libraries with the terms needed for an exact description of catalog practices. Also because of lack of experience with OCLC, many librarians had difficulty in understanding the options available. As a result, profiling generally had two stages—the first developed a profile that reproduced the library’s existing practices. About a year later, having developed a hands-on understanding of OCLC options, profiles were rewritten to take advantage of those options.

Training. The project director and her assistant, both of whom had MLS degrees and technical service backgrounds, had responsibility for training for OCLC use. Throughout the project, training was provided on three levels. Workshops were designed to cover the basics of each OCLC operation in small group sessions of six to eight people. After the workshop, project staff were available, if desired by the library, to work with trainees one-to-one at terminals for about half a day. Finally, all library staff members were encouraged to call the project office as problems arose, or to check records they wished to put in their save files, or if unclear information appeared on the screen.

The general philosophy in all the training sessions was to teach participants what they must know to handle 90 percent of their materials. Most staff members learned basic OCLC editing quickly, without further training because most libraries made very few changes to cataloging records. The changes made fell into two areas, call numbers or subject headings. The staff members who required the most reinforcement after the initial training sessions were those with the fewest books to catalog.

Because the hi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Editor’s Note

- Foreword

- Cost and Benefits of OCLC Use in Small and Medium Size Public Libraries

- The Kewanee Public Library Votes Yes on OCLC

- We’ll Wait and See

- A WLN Dilemma

- Linking CLSI and UTLAS to Meet Local Needs

- Present and Future Network Base for New Mexico’s Public Libraries

- Networking at the Principal Public Library in Rhode Island: A Decade of Change