eBook - ePub

Energy Performance Buildings

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Energy Performance Buildings

About this book

This book deals with the concerns of everyone involved with the use of energy in buildings. It is written principle for those with a direct professional interest in the energy performance of buildings.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

ENERGY AND BUILDING — EVOLVING CONCERNS

I. Introduction

This book addresses some of the more important aspects of the energy performance of commercial and institutional buildings. The central concept of the book is that energy performance is the concern, not only of building owners and designers, but also of national governments and building users. This concept provides the framework for the book as a whole, and is described in more detail in Chapter 2.

Implicit in the concept is the assumption that those concerned will wish to improve the energy performance of the buildings for which they are responsible. There is some evidence that this assumption is gaining validity. It is also clear that there are still many impediments to the translation of these wishes into positive action. Many of these impediments relate to existing practices in the financing, owning, designing, construction, and use of buildings.

We have two main aims. The first is to explain the consequences of current practices, as revealed by studies of the energy performance of existing buildings. The second is to provide a basis from which new practices may be developed and new methods of assessing the energy performance of a building may be produced.

Of course, concern with the energy performance of buildings is not a recent phenomenon; it is one which has exercised mankind’s ingenuity since time immemorial. This book can only be a snapshot in what is a rapidly changing scene. It can be neither exhaustive nor definitive, but rather provides an in-depth picture of the state-of-the-art in building energy performance (in keeping with the concept of the CRC Press Uniscience Series).

This opening chapter deals with the evolving concerns of energy and buildings. The first section outlines the history of the part played by energy considerations in building design and reviews current thinking on the subject of building performance in general. The second section explores elements of the concept of building energy performance; how to measure it, factors affecting it, and so on. The third and final section reviews theoretical models of energy performance and identifies the relevant interest groups.

II. Historical Perspective

Before attempting to deal with the idea of the energy performance of buildings, it is useful to explore the two main elements of that idea: on the one hand, energy and buildings; on the other, building performance.

Energy considerations have influenced the design and operation of virtually all buildings since time immemorial and it is important to see current studies in context. More recently, the building performance concept has been used in an attempt to provide a basis for the appraisal and specification of buildings. The merging of these two elements into models of building energy performance will be described later.

A. Energy and Buildings: A Brief Historical Introduction

Present day buildings tend to be energy dependent to such a degree that without it they could not be operated or inhabited. Energy is primarily used for the heating, ventilating, cooling, and lighting of buildings. Secondary uses include hot water service heating, vertical transportation, etc. The amount of energy actually consumed depends on the design of the fabric of the building and its systems and how they are operated.

The opportunity for such a high level of energy dependence was not available in the past, and primitive man has left abundant evidence of energy-conscious design and construction. Clearly, energy efficiency is a vitally important design criterion when fossil fuels are not available. In many parts of the world primitive man coped (indeed survived) by developing building designs that made use of the available material resources in such a way as to gain the maximum benefit from the climatic conditions.

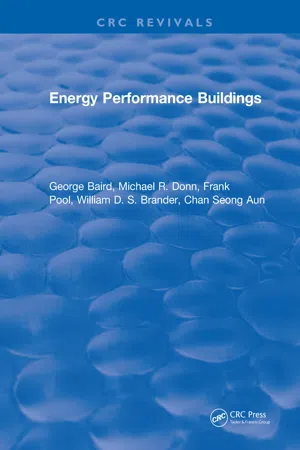

FIGURE 1. Daily variation in the inside air temperature of an igloo (at sleeping platform level) under typical arctic temperature conditions (From Fitch, J. M. and Branch, D. P., Sci. Am., 203, 6, 1960. Copyright 1960 by Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved).

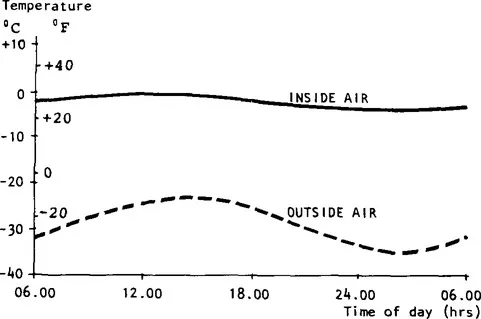

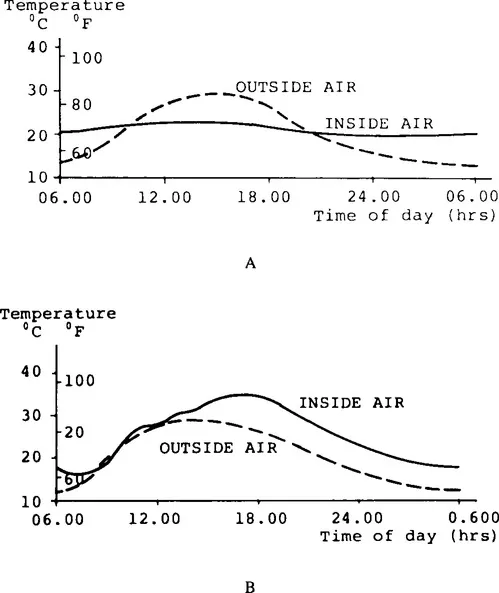

FIGURE 2. Daily variation in the inside air temperature of an adobe house under high daytime temperature conditions (From Fitch, J. M. and Branch, D. P., Sci. Am., 203, 6, 1960. Copyright 1960 by Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved).

The igloo and the adobe house are two archetypes of such designs. According to Fitch and Branch1“...it would be hard to conceive of a better shelter against the arctic winter than the igloo.” Figure 1 shows the remarkable temperatures achieved within an igloo, with the occupants and their oil lamps as the only available sources of heat.

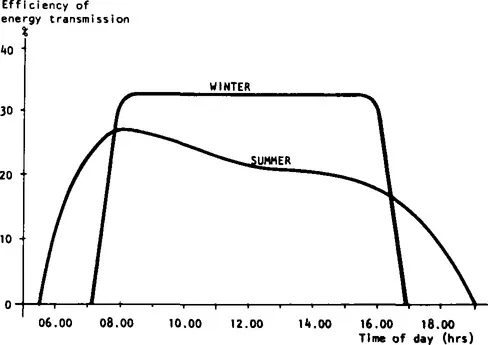

Figure 2 shows what is feasible at another end of the climatic scale, with a well-designed adobe house. In this instance, the wide daily external temperature swing is reduced, and the effect of the high daytime peak delayed until late evening. In his analysis, Knowles2 graphically illustrated how this building type was designed to obtain maximum benefit from winter sunshine, while minimizing summer heat gains (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Daily variation in solar energy transmission at Pueblo Bonita, N. M. (11th Century A.D.) under summer and winter conditions. Notes: (1) Efficiency is given by the expression (E,/Eml) per cent where E, = energy transmitted to the interior of the pueblo and Eml = transmitted energy if all the surfaces of the form were normal to the sun’s rays. (2) The winter efficiency is 33% (from 08.00 to 16.00 hr) by comparison with the summer average of 22.6%. (3) The summer efficiency has the desirable characteristic of an early moming peak followed by a gradual reduction as the day progresses. (4) The vertical sun facing walls have high thermal transmission coefficients and high heat storage capacities, by comparison with the horizontal roof structures. (From Knowles, R., Energy and Form: An Ecological Approach to Urban Growth, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1974. With permission.)

Other examples of primitive man’s awareness of climatic design principles include the structural forms that were used to cope with tropical climatic conditions of high solar radiation and heavy rainfall combined with moderate temperatures, and the variations that have evolved to cope with subtropical conditions. Fitch and Branch1 are at pains to point out the “delicacy and precision” of these solutions which must have required “real analytical ability” of the designer.

By comparison, they suggest, Western man consistently underestimates the environmental forces of nature and overestimates his own technological capacities. Figure 4, for example, gives the results of tests on indigenous mud-brick buildings in Egypt and Oman in comparison with modem concrete buildings in the same locations.3 Figure 4A illustrates the capacity of mud-brick to mitigate the outside temperature. By contrast, the inside air temperature of the concrete building (Figure 4B) exceeds that outside, and the temperature swing is several times that of the mud-brick building.

There appears to be very little published quantitative analysis (of the type presented in Figures 1 to 4) of the performance of the buildings constructed by the Greek, Roman, and other preindustrial civilizations. However, there is ample evidence that designers of these times were well aware of climatic considerations and would apply energy-conscious principles where necessary. This does not imply that earlier generations always gave a high priority to climatic considerations when designing buildings. Then, as perhaps now, “sociocultural factors” were of fundamental importance, with “modifying factors” such as climate, construction, materials, and techniques having a lower order of priority.4

The Greeks were well aware of the solar design principles applicable to their latitude and temperature conditions. Individual houses had openings oriented south to allow sun penetration in winter, but were appropriately shaded to keep it out in summer. Urban planning practices were evolved so that individual buildings could utilize solar radiation.5

FIGURE 4. Comparison of the inside air temperatures in a mud-brick room and a prefab concrete room. (A) Mud-brick room. (B) Prefab concrete room. (From Cain, A., Afshar, F., and Norton, J., Architectural Design, 4/75, 207. With permission.)

The Romans were also fairly inventive when it came to the design and application of heating and ventilating systems in their buildings. Underfloor warm air heating systems had been employed to heat bath houses and villas, but the furnaces required large quantities of wood or charcoal. In the face of the resulting shortages of firewood the Romans adopted many of the design principles previously used by the Greeks. In practice, these were adjusted to take account of the wider climatic range embraced by the Roman empire, modified to take account of new developments such as the glazed window, and enhanced by the use of such devices as solar-absorbing floor coverings.6 The writings of the 1st century B.C. Roman architect Vitruvius embody many recommendations that relate directly to energy-conscious architectural design.7

Little further development appears to have taken place until after the Dark Ages. Towards the end of that period the manorial system had taken hold over much of Europe and life, in winter at any rate, centered around the fire in the hall.8 At that time, a hole in the roof was the only provision for exhausting the smoke. It has been suggested that it was during the Little Ice Age which occurred during the 13th and 14th centuries, that the chimney was increasingly used in buildings. As a result, smaller rooms could be readily heated and the communal life of the great hall with its central fire gave way to a more segregated style, both of lif...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- The Authors

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Energy and Building — Evolving Concerns

- Chapter 2 Building Energy Performance — a New Framework

- Chapter 3 National Concerns — Institutional Roles and Energy Standards

- Chapter 4 Owner Concerns

- Chapter 5 Designer Concerns — Capital Energy Requirements

- Chapter 6 Designer Concerns — Systems Energy Consumption

- Chapter 7 User Concerns — Energy Management and Analysis

- Chapter 8 Building Energy Performance — Future Concerns

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Energy Performance Buildings by George Baird,Michael R. Donn,Frank Pool,William D. S. Brander,Chan Seong Aun in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.