![]()

CHAPTER I

A FEW NOTES ON THE HISTORY OF YORUBALAND

Introductory Historical Remarks

FROM Dalzel’s History of Dahomey, 1793, it would seem that Yorubaland about the year 1700 was under one King, or Alafin, who resided at Old Oyo1 or Katunga. That this kingdom when united was a very powerful one is shown from the fact that until the year 1818 the Dahomi paid tribute to the Alafin of Oyo.

It is only from this date (1700), when the decadence of the Yoruba Kingdom had set in, that the native chroniclers can give us any definite knowledge of the Yoruba history. From this time we have a list of Alafins given to us.

1. Ajagbo.

2. Abiodun.

3. Arogangan; during whose reign his nephew Afonja raised an insurrection and so hurried on the downfall of the Kingdom.

4. Adebo.

5. Maku.

6. An Interregnum during which the Obashorun or Prime Minister of the Alafin seems to have kept the State from actual ruin.

7. Majotu.

8. Amodo, about 1825.

About 1830 Lander visited Old Oyo, but between 1833 and 1835 the Mohammedans captured and destroyed the old town, and the Yoruba were obliged to found a new capital where Oyo now stands.

It was about this time also that the Egba declared their independence. They were finally driven out of the country that they, as a section of the Yoruba people, occupied, and in 1838 they founded their present capital, Abeokuta.

A chief called Lishabi is said to have led them to Abeokuta, and to show how near to the mythological period of their history we even now are I am able to give you the story of how Lishabi when defeated by the Dahomi descended into the earth.

How Lishabi descended into the Earth

Lishabi was a great warrior who lived at Ikija, Abeokuta. One day when there was a great battle between the Egba and Dahomi, and the Egba were put to flight and many killed, Lishabi was so ashamed that he would not return to Abeokuta, and so pointing his sword to the earth asked her to open. She opened and he went headlong into her depths. His sword is there to this day marking the place where he thrust ft into the earth. His brass chain is also there; and if anyone begins to draw the chain out he can pull about 40 feet of it out of the ground, but then Lishabi pulls it back again. Many people have seen pigeons fly out of the place, they feed here and there, and then go back, so they know Lishabi has his house there. One man tried to make a farm there and started felling the bush, but he died, so now no one dares to farm in this place. And the people of Ikija go there yearly to worship him. They offer rams, goats, fowls, and yams to him.

By the year 1840 the seeds of dissension sown by Afonja had spread so rapidly that we find the proud Kingdom of the Yoruba people split up into a number of so-called independent states.

Illorin had been lost to the Alafin, and is now inhabited by a mixture of Hausa, Fulah, and Yoruba.

Ibadan, a semi-independent state, still recognises the Alafin and pays tribute yearly,

The Egba, a fine race of agriculturists, declare that they are quite independent, as also do the Ijebu, Ilesha, Ife, and Iketu (now in French territory).

From 1840 to 1886, when the British Government intervened as peace-maker, wars between these parts of the Yoruba people were constant. From that date until 1892 the peace-maker has had to punish the Ijebu and Egba for closing their trade roads.

In August 1861 Docemo ceded Lagos to the British. In 1863 Kosoko ceded Palma and Lekki, much to the disgust of the chief of Epe, who refused to cede his rights and was punished for it. And in the same year the chiefs of Badagry ceded their territory to the British.

Lagos became a great slaving port about the year 1815 when the King of Benin and a few other chiefs refused to allow slaves to be exported from their territories. The original inhabitants of Lagos were a mixture of Bini and Yoruba people. When it became a port of export for slaves, such slaves as became residents as labourers and servants of the slave dealers and merchants added their quota to the population; and when after 1861 it became a British colony many freed slaves from Sierra Leone and other parts, more especially Brazil, made their homes there.

The Colony of Lagos in 1863 rejoiced in a separate Government, but in 1866 with the other West Coast Settlements it was attached to Sierra Leone.

In 1874, after the Ashanti war, Lagos became part of the New Gold Coast Colony and in 1886 it became a distant Crown Colony, since when its progress has been phenomenal.

The formation of the Niger and adjacent territories into a Royal Charter Co. with Mr. (now Sir) G. Goldie as Deputy Governor, following the declaration of a Protectorate of the Niger Territories by the British Government in June 1885, is so well known a fact that the mere mention of the event is sufficient.

And I need only jog my reader’s memory to call to his mind a knowledge of the time when that part of the West Coast which finally became S. Nigeria was more or less governed by Consuls resident in the Island of Fernando Po, called by Burton the Foreign Office Grave.

The time came when the Foreign Office having worked up the “Raw Material” the finer processes of the Colonial Office were applied.

In 1889 I was present at a meeting in Calabar when the Special Commissioner Major (now Sir) Claude MacDonald interviewed the Chiefs, and on the 1 st August 1891 the Oil Rivers commenced a new era under the title of the Oil Rivers Protectorate.

The Oil Rivers Protectorare became what is now known as Old Southern Nigeria while the rest of the Niger Protectorate became Northern Nigeria.

In 1906 Southern Nigeria and the Colony of Lagos and Protectorate were amalgamated, and the Colony of Lagos and Protectorate became the Western Province of what is to-day known as the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria.

The following notes refer chiefly to this Western Province, known generally as Yorubaland.

The Origin of the Seven Yoruba States

In “At the Back of the Black Man’s Mind” I pointed out that the Congo was composed of a central Kingdom surrounded by other six states, also that each of these states was divided into seven provinces, six surrounding a seventh where the Fumu or Chief of the sub-Kingdom resided.

F.S., in the Nigerian Chronicle, in a paper entitled “A Chapter in the History of the Yoruba Country,” writes:—“Yoruba is one of the seven countries or states which the Hausa people term Bansa Bokoi (the vulgar seven) in contradistinction to Hausa Bokoi (the Hausa seven); the latter term is applied to the original Hausa states and the former to seven countries or states originating from the same races as the Hausa people, but which do not form part of the Hausa nation.”

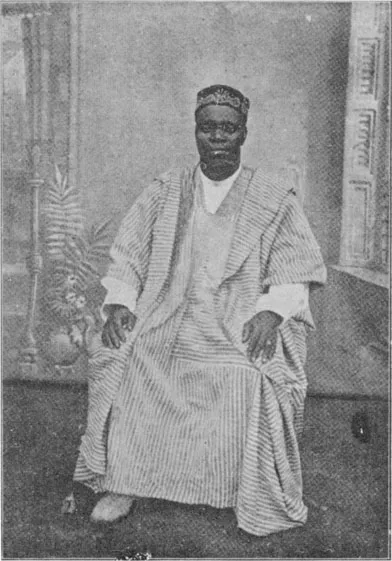

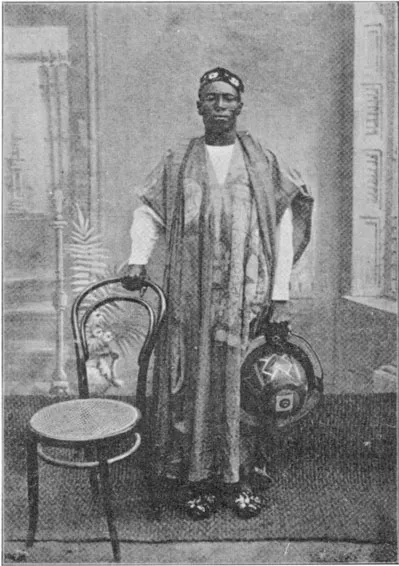

LAGOS TYPE.

LAGOS TYPE.

[Face p. 10.

He goes on to say, “There can be little doubt that the Yoruba people are at least intimately connected with the Orientals. Their customs bear a remarkable resemblance to those of the races of Asia. Their vocabulary teems with words derived from some of the Semitic languages; and there are many natives of Yorubaland to be found having features very much like those of Syrians or Arabians.”

Most natives I have talked to on this subject are conscious of this origin from a superior race, and the marked superiority of the Yoruba people to their neighbours certainly points to something of the sort.

But many also are only too anxious to ignore the fact that the country was peopled by pagan Africans and that they are consequently in reality a mixed race among whom paganism persists.

Now these dear old pagans are said to have given the name of their Creator Odudua to the leader of the Bornu immigrants whose real name has been forgotten, and there is a legend that a Hausa Mussulman came to Ife, the religious capital of Yorubaland, and told them to “worship Allah.” “He created the mountains, He created the lowlands, He created everything, He created us.” But in a critcism by the editor of the Nigerian Chronicle the coming of the Mussulman must be placed at a much earlier date than that given by F.S., i.e. many years after the eleventh or twelfth century of the Christian Era.

It is possible, however, that Mussulman influence, at whatever date it first made its appearance, may have been the cause of the reorganisation of the religion of the pagan Yoruba. It was perhaps the means of putting Jakuta or Shango, the thunder and lightning God, in his place and the substituting of Olorun, the owner of heaven, for that great Orisha.1

To this time, then, the Yoruba pagan may owe, not the origin of his Orishas, but the order in which the greater ones have been handed down to the present generation.

Mr. George, in Historical Notes on the Yoruba Country, gives us another variant of the historical traditions of the Yoruba. Mr. George says:—“There are many traditions about the Yoruba Kingdom. We quote one which says that the Yoruba Kingdom was peopled by six brothers; that at the departure of their father to his home in the north, they left their mother, whose name was Omonide, and travelled downward. These formed six distinct kingdoms and are known to this day by the respective regal titles: Alake, Alaketu, Onisabe of Sabe, Onila of Ila, Oni Bini or Ibini or Benin, and Oloyo of Oyo. Some time after they migrated downwards, their mother hearing that they were settled decided to visit them. On leaving home, she took with her the piece of cloth, the band or Oja, with which she had secured them on her back when they were young, and the small pot, or Oru, in which she had prepared their infant drink. She thought that perhaps, as they had become Kings, they might ungratefully despise her, and she was ready to curse all and any of them that might do so. Accordingly, she went first to Alaketu1 the eldest. She was received with all the honours of her position. She was pleased at this reception, and after remaining some time she went to visit the Alake, where she was similarly treated. She spent some time here purposing to visit her other children. Ultimately she fell ill and died.

“It is said that she, being pleased with her reception by the Alaketu, gave him on her departure the band or Oja with which she had secured her children.… She told him that the cloth was an important charm which possessed the power of good and ill; that good or evil will follow anyone according to his wish or utterance while he holds or puts on this cloth. It is said that one of the Kings of Ketu, who never would go out on any public occasion without having on this cloth, was once upbraided by his Chiefs for it, and was threatened to be driven away from the throne.

“An altercation ensued, during which he made certain imprecations which are said to be operating upon the country and people to this time. That since he was disgraced for having on an old cloth, made brown by the dust of age, their country will ever be red and dust covered, and their garment be it ever so clean will appear a...