- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geography and Soil Properties

About this book

This book, first published in 1978, provides a comprehensive guide to soil properties in any major world region. It emphasizes the significance of the spatial changes in soil patterns, the environmental influence on soils, and their temporal changes, but focuses attention on the systematic examination of soil properties and their reciprocal effects. It covers such important topics as the mineral composition of different soils, their organic matter, structure and porosity, chemical make-up and mechanical properties.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Geography and soils

1.1 Physical geography and soils

1.1.1 HYDROLOGY AND SOILS

(a) Soils and the hydrological cycle

At the critical interface in the hydrological cycle, where precipitation meets the soil, water is either absorbed into the soil or it runs off on the surface. When absorbed in sufficient quantities, soil water favours the growth of economically valuable crops or contributes to groundwater reserves. If absorbed in smaller amounts, much moisture may be lost in evapotranspiration and an economically valueless crop may result. If precipitation runs off on the surface, it may be channelled for irrigation or impounded for urban and industrial use. Alternatively, runoff may mount into destructive floods, constitute an erosion risk, and as such create sedimentation problems downchannel and in estuaries.

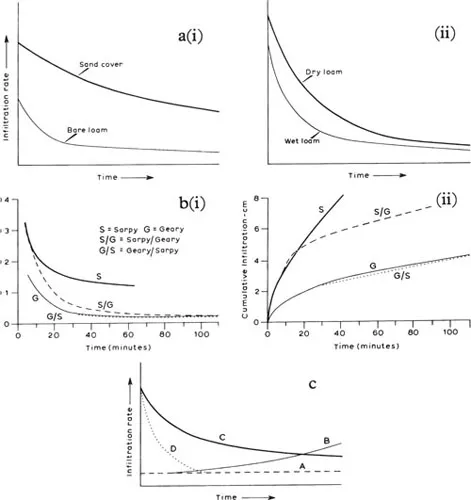

Whether precipitation takes beneficial or destructive routes is determined largely by the properties of the surface horizon of the soil. Infiltration rates depend on the water physical properties of the soil, especially its permeability. For instance, infiltration decreases with increasing clay content and increases with greater porosity in the soil (fig. 1.1a). A major factor is also simply the amount of water already occupying the soil pores prior to a given precipitation event. Permeability may change with depth. If subsoils are less permeable than surface horizons, the lower horizons control infiltration rates and the upper horizons may become saturated rapidly (fig. 1.1b). Alternatively, a surface horizon or crust may develop and be less permeable than the subsoil if rainbeat compacts a poorly structured soil and washes fine particles into the pores of the surface layers. This occurrence may reduce permeability within the course of one storm.

Figure 1.1 Effect of soil texture, layering and moisture content, and temperature on infiltration.

aGeneralized variation in infiltration curves, related to soil texture (i) and to preceding moisture content of the soil (ii).

bPredicted influence of layered combinations of soils and uniform soils on infiltration (Hanks and Bowers, 1962). The coarse-over-fine layered soil (Sarpy/Geary) was identical with the coarser soil until the wetting front reached the finer soil.

cGeneralized infiltration curves for frozen soils (Gray, 1970).

ASoil frozen when saturated, or persistence of impervious ice layer during melting.

BSoil frozen at high moisture content, with meltwater progressively melting ice-filled pores.

CSoil frozen at low moisture contents and at temperatures near freezing, then thawed by meltwater.

DSoil frozen at low moisture contents but at temperatures well below freezing; water entering pores is frozen and infiltration is inhibited.

Soil temperatures of field soils of different textures concern the hydrologist. If clays crack on drying, the first ensuing rains infiltrate rapidly. Where freezing occurs, apart from depth and persistence of frost in the soil, the changes which may take place within the frozen layer during freeze–thaw cycles are particularly significant. The type of response depends on such factors as the degree to which a soil’s pores are saturated with moisture prior to freezing or on thawing, or on the degree of freezing when water first enters a dry soil (fig. 1.1c). For example, the common spring floods in the drift-free area of the upper Mississippi valley result primarily from restricted infiltration into frozen soils.

(b) Soils and water quality

It is increasingly doubted whether the soil can retain sufficient of added chemicals to keep their levels low in nearby fresh water bodies. In particular, nitrification occurs rapidly in most soils and excessive N and P are a major cause of increased growth of undesirable aquatic vegetation in lakes and streams. Deleterious side-effects also include algal blooms, fish kills, filter clogging, and undesirable taste and smell in drinking waters. Aesthetic qualities in the environment may also deteriorate. Methema-globinemia in animals and young infants has been attributed to excessive nitrates in drinking water. In semi-arid and desert soils, irrigation is usually responsible for secondary salinization processes. The suitability of waters for irrigation is, therefore, being increasingly evaluated in conjunction with studies of soil characteristics. Otherwise, solutes in soil water may create saline, sodic or toxic levels which are hazardous for crop growth or to animals and man consuming these crops (Bettenay et al. 1964).

The soil has been for ages a major medium for the disposal of a variety of wastes, owing to its colloidal organic matter and other related properties. Organic compounds and natural wastes added to the soil are usually destroyed in the upper zones or are retained in the surface horizons long enough for them to be entirely mineralized. Nonetheless, even the slow release of a toxic compound from the soil affects the quality of water for drinking and for agricultural and industrial purposes. Deterioration of this type has become more marked with the extension of urban residential areas and with the increased use of biocides made of synthetic compounds which are not readily degraded by soil processes.

Clearly, to comprehend quantities and qualities of water as a prime natural resource, the geographer must understand the role and significance of several characteristics of the soil.

1.1.2 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOILS

The study of the hydrophysical characteristics of soils and their response to precipitation in particular, enlightens the geomorphologist about the nature of geomorphological processes (Reid 1973). Furthermore, soil profile characteristics increasingly afford precise information on the spans of time which must elapse for such processes to have some visible if not measurable effect on landsurface evolution. In fact, it can be claimed that the geomorphological history of the earth’s landsurface and the history of soil formation have many similar or parallel or even identical characteristics (Daniels et al. 1971).

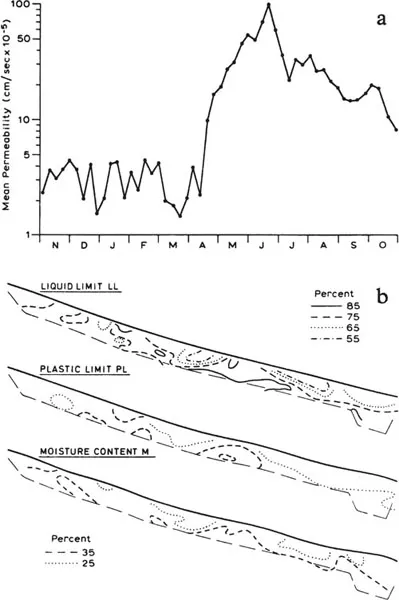

Figure 1.2 Geomorphological significance of soil moisture.

aDifferences between topsoil and subsoil permeability, due to seasonal swelling of the clay fraction (Arnett, 1976). This contrast appears to account for much of the variations in interflow regimes in these soils, developed on Jurassic strata in the North York Moors.

bMoisture content and the Atterberg limits (plastic limit and liquid limit) which describe the engineering stability of the soil in a coastal landslip area near Charmouth, Dorset (Denness et al., 1975). The profile is loom long.

(a) Contemporary weathering processes

In studying water movement through the soil, like the hydrologist, the geomorphologist is concerned with porosity and permeability and the degree to which their indices decline with finer particle sizes or are affected by other soil characteristics such as aggregation, compaction, or the dispersion or swelling characteristics of the clay fraction. The degree to which porosity and permeability decrease with depth in the soil is a particularly significant geomorphological factor (fig. 1.2a). In addition, soil water is the fundamental control on certain mechanical characteristics of soils. In areas where mass-movement of the soil or landslipping occurs, the amount of water in the soil may reach such levels that the soil behaves like a plastic material or even as a liquid (fig. 1.2b). Like such soil mechanics investigations by the civil engineer, studies of soil erosion by the agricultural engineer have a critical relevance for the geomorphologist. Soil temperatures are significant where their changes induce freezing and thawing or wetting and drying in the surface, with knowledge about the case of permanently frozen ground being essential. Data describing soil air are equally relevant as the carbon dioxide released by biochemical decomposition of organic matter and by plant root respiration in the soil greatly increases the potential solutional activity of soil water when it encounters rock fragments or bedrock.

(b) Relict landsurfaces and ancient soils

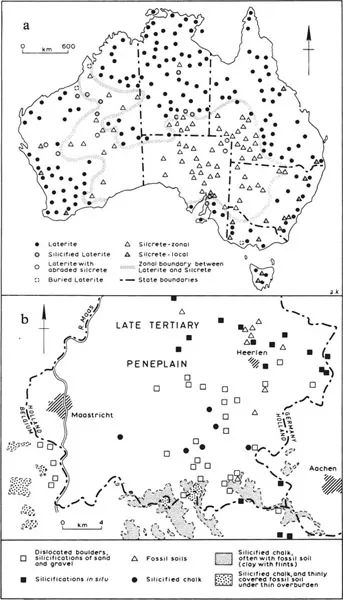

One of the most precise statements which W. M. Davis made was that weathered soils to a depth of 50 ft might characterize the surface of a peneplain. Indeed, pedological evidence supports the interpretation of the landsurface of South Limburg as part of a Tertiary and Late-Tertiary peneplain (fig. 1.3b). Its characteristics include thin local deposits of much weathered and pitted sand and gravel, strongly weathered outcrops of bedrock, deep relict soils and extensive surface silification. Australia in Late-Tertiary times was characterized by a general planation surface with minor relief and with limited areas of higher land (fig. 1.3a).

The characteristics of ancient soils do not necessarily corroborate interpretations of landsurfaces as former peneplains. For instance, soil mapping and associated laboratory studies on samples from various parts of the Chalk outcrop in southern England illustrate the importance of continued subaerial weathering during the Quaternary in the evolution of the landsurface (Catt and Hodgson 1976). However, where they occur, landsurfaces capped by laterite, calcrete, or silcrete demand the geomorphologist’s particular attention and invite his understanding of these distinctive horizons as extreme cases in the expression of soil weathering processes (Lepsch et al. 1977).

Figure 1.3 Relict weathering features on ancient landsurfaces.

aDistribution of laterite and silcrete in Australia (Stephens, 1971).

bDistribution of silicifications and fossil soils in South Limberg (Broek and Waals, 1967).

(c) Depositional landsurfaces and soils

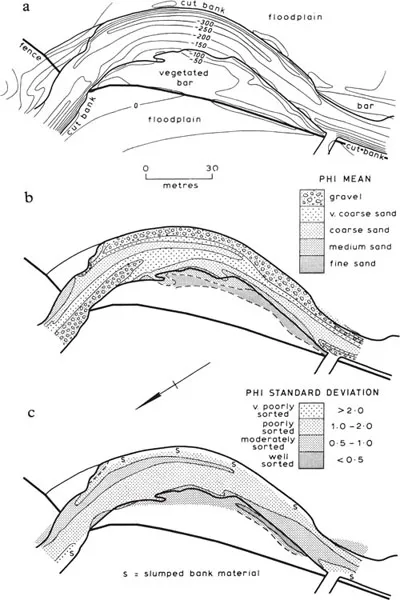

Floodplain soils reflect the various fluvial processes of former river bed, floodplain, delta or estuary. These are discernible in a specific zonality and pattern of change in the soil cover. Studies of contemporary processes show that coarse-textured soils develop in the portion of the floodplain adjacent to the river (fig. 1.4). Soils developed in slack water sediments are widely distributed and may be particularly significant for agriculture, as noted in the Lower Ohio River floodplain. Chemical processes in floodplain soils are also an expression of distinctive local conditions. These are related to changes in oxidation–reduction conditions, a change in soil reaction, or to the formation of organomineral compounds. In particular, the accumulation of iron and its geochemical associates characterizes certain zones, past and present in floodplains. In subhumid climates, the formation of a solonchak water regime is associated with virtually enclosed drainage areas in floodplains. Surface and groundwaters in such hollows are almost entirely lost by evapotranspiration.

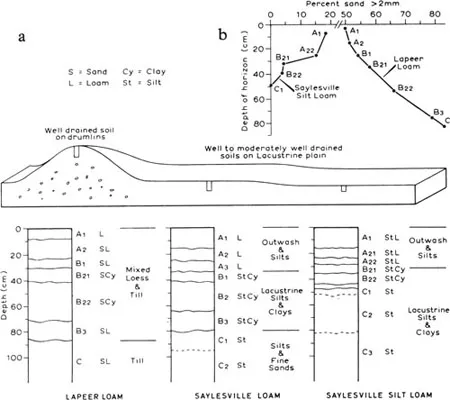

Soil characteristics are useful in differentiating patterns of glacial deposition and outwash, particularly where periglacial conditions favoured wind-transport too. Organic soils frequently have developed in water-logged depressions, but distinctive, very soft and highly compressible soils indicate where post-glacial lakes were impounded, as observable in soils of lowland Ayrshire, or in the glacial landsurface of Wisconsin (fig. 1.5).

(d) Buried soils

Buried soils are particularly common in areas where the summer thaw of frozen ground leads to lower slopes being covered with solifluction lobes. Where buried soils occur in fluvial depositional zones, their presence indicates that the deposition rate and the associated erosion and soil development rates have been periodic. For example, in New Mexico in the Jornada del Muerto basin, gullies in an alluvial fan expose a succession of four major sediments, each of which has a distinct soil profile. In such semi-arid areas, the buried soil usually includes a carbonate-enriched horizon (fig. 1.6a). Nearby, buried charcoal horizons were found, indicating that several deposits of alluvium are present, ranging in age from less than 1100 years to over 5000 years B.P. Climatic change, causing a decrease in vegetative cover, could have started the pronounced erosion of Pleistocene soils, resulting in the deposition of these highly calcareous Recent sediments (fig. 1.6b).

Figure 1.4 Particle characteristics of a dynamic depositional landform (Bridge and Jarvis, 1976), a meander in the floodplain of the South Esk, Glen Clova, Scotland.

Figure 1.5 Soil particle and profile characteristics of relict depositional landforms Borchardt et al., 1968), in a glaciated landscape of south-eastern Wisconsin.

aThe moderately dolomitic sandy Lapeer loam on the glacial till of the drumlins merges downslope into the highly dolomitic Saylesville silty clay loam of the glacio-lacustrine plains.

bSand content decreases with proximity to the soil surface in the Lapeer soil, but increases in the Saylesville soil. There is an apparent dilution of sand of glacial till by aeolian silt and clay. One quarter of the 86 cm deep soil incorporates leached loess which would have been laid down as a 22 cm thick cover.

Radiocarbon datings of buried soils are of particular interest to the geographer, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 Geography and soils

- 2 The mineral fraction of the soil

- 3 Soil organic matter

- 4 Soil structure and porosity

- 5 Physical properties of the soil

- 6 Chemical properties of the soil

- 7 Soil mechanical properties

- 8 Soil colour

- Bibliography

- Appendix: soil names

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Geography and Soil Properties by A.F. Pitty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.