- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Labor and Creativity in New York’s Global Fashion Industry

About this book

This book tells the story of fashion workers engaged in the labor of design and the material making of New York fashion.

Christina H. Moon offers an illuminating ethnography into the various sites and practices that make up fashion labor in sample rooms, design studios, runways, factories, and design schools of the New York fashion world. By exploring the work practices, social worlds, and aspirations of fashion workers, this book offers a unique look into the meaning of labor and creativity in 21st century global fashion.

This book will be of interest to scholars in design studies, fashion history, and fashion labor.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Labor and Creativity in New York’s Global Fashion Industry by Christina H. Moon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Shoddy Seams

The Decline of the New York Garment Industry and Its Transformation Into New York Fashion

By the 1990s, capital, people, and things moved around the world. Distances were connected with expansive highways, shipping routes, and air travel. Mass media and telecommunication technologies could now connect even the most remote corners of the world. The “time-space compressions” of late capitalism collapsed geographic distances and the rhythms of daily life, speeding up what were social and economic processes that were cultivated over long periods of time.1 One could now get on a plane and be in another place the next day, with communications instant by fax and email. The end of one workday could now be the start of another in a different place, in what was now a 24-hour workday. In manufacturing, products could now be made as quickly as they were consumed. Manufacturers no longer set the trends but rather chased them down, since the trendiness of things quickly and relentlessly obsolesced in what were now deemed “buyer-driven” commodity chains.2 The global restructuring of financial landscapes had completely reordered global modes of production, dramatically shifting the relationship between production, distribution, and consumption. Labor had become “flexible”—central to the movement and maintenance of markets and commodities.3

Production of a single piece of clothing could now take place in multiple countries, cities, regions, and factories around the world. Not only that, when coordinated, the breaking down of the assembly to the smallest, most minute tasks performed in different parts of the world vastly increased the volume and kinds of commodities that could be made. Free trade zones, special economic zones, and new spaces of exception rearranged laws, and trade regulations were suspended, adjusted, or made malleable to what was now a global economy that cultivated exporting goals. Textiles could be made in East and Southeast Asia, its pieces cut out in places like Mexico, then sewn in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Central and South America, and shipped back into the US, all duty-free. Corporations invested their capital in technological and machinery assets in places with “healthy” and “continuous” populations of young female workforces who looked for work and would take any wage at all. Global assembly lines and international divisions of labor grew and grew in these next two decades. These chains, as the anthropologist Anna Tsing describes them, were the unruly “value mining” entities that resulted in uneven concentrations of power, capital, privilege, and prosperity across nations that sourced the global commodity chain.4

While economic policy reports of the 1990s hailed the emergence of a new global era of economic progress in a world without borders and full of growing markets, entire American communities whose work depended upon a mill or plant for a generation or two lost their livelihoods.5 Although the industry and the Garment District itself had experienced the consistent offshoring of mass garment production since the 1970s, it was not until the globalizing trade acts of the 1990s that the New York Garment District was thought to be “doomed” for good. Until 1994, the domestic US garment industry was protected against foreign competition by tariffs and quotas under the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA), a piece of US legislation created in 1974 that set export quotas on all textile manufacturing nations. In 1994, however, three new trade agreements emerged—the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), and the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) were both signed as part of the rush to institute global free trade and economic liberalism with the promise of bolstering US manufacturing. NAFTA would make visible these new reconfigurations and special arrangements of capital, labor, and laws, by eliminating all trade barriers between the US, Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean and transferring technology, plants, equipment, and labor across borders to produce garments that could be shipped back into US markets duty-free.6 Both treaties, however, set into motion the elimination of all trade protections on the domestic industry and propelled the export of the majority of domestic garment production jobs and textile production abroad. An elaborate system of subcontracting emerged, which created tremendous competitive pressures on the lowest rungs of production because contracting factories competed with one other for business by bidding down contracts to the lowest legal minimum wages. Finally, on January 1, 2005, the World Trade Organization (WTO) terminated the MFA’s quota system for apparel exactly at midnight, instituting an era of unregulated, quota-free markets for clothes.

The Garment Industry Is Dying

“The Garment Industry Is Dying” was the kind of titled article one read in the New York Times every few months from the 1990s onwards, as if this New York neighborhood, once living, was on its last breath.7 When I showed up in the Garment District in 2006, it felt as if it were already “too late.” I had been given a list of factory owners and their locations by an official at the Business Improvement Center and showed up to factories hoping for an interview. But time and time again, I’d show up to a new office or showroom space and find that the factory had been shut down. At one point I went to a location on the eighth floor of a building on 37th Street, only to find newly carpeted floors and office cubicles when the elevator doors opened. Frustrated, I inquired with the security guards in the front lobby—one who pulled out an old Rolodex full of stapled and browned company cards—and dialed a number on an old rotary phone. He handed me the receiver. “Hello? Who is this?” asked the person on the line. I gave my polite introduction, only to be cut off. The former factory owner curtly replied, “The Garment District is destroyed. Anyone with a business in the industry needs to get out. It’s done. It’s gone. They’ve destroyed it all,” and then hung up the phone.

Who were “they” who destroyed the district? Eventually, I learned that “they” could mean the legislators and politicians who had loosened trade laws, created NAFTA and GATT, and allowed in cheap imports or the large manufacturers and design corporations that accelerated the move to produce garments overseas in countries like China. “They” were the American public—consumers who no longer cared for the “Made in America” clothing label, were ignorant about where their clothing had been made, and didn’t care about its “quality.” “They” were the corrupt unions who left their workers, 30 years later, hardly without a pension, or the anti-sweatshop protestors who scared manufacturers out of producing locally. “They” were the growing numbers of Korean and Chinese factory owners who were willing to undercut the price of labor by employing nonunionized sewing operators. Tales of the New York Garment District from the 1990s and 2000s were bitter stories, of villains turned victims and victims turned villains, without recognition of who won or lost. “What happened,” they told me, wasn’t just the chronology of trade laws or NAFTA and GATT histories, but the experience of being cheated, lied to, undercut, and duped by competitors, the government, the American public, and “the country.” The only people who were left to talk to were the “survivors” who shared with me stories of those who’d gone missing in those two decades. If the Garment District was once an ecosystem, a fabric of all kinds of business owners, these survivors of the industry told me how the seams of the district had come undone.

Working as a fashion intern for a Seventh Avenue multinational corporation, my daily rounds had me weaving in and out of what was thought to be the last remaining factories of the New York Garment District, from 32nd Street to 36th street, from the 11th floor to the 16th floor, from wide open loft spaces to tiny cramped workshops, sweatshops, or studios. Beyond the chronology of trade laws that impacted life in the Garment District, the barely surviving small-time business owners and garment factory owners I interviewed, 12 in total, described instead the changes to work in the local district, their observations of the physical changes to the neighborhood, and the materiality of fashion itself from its sourcing to the increased intricacies of sewing it now required.

Sal, the owner of Steinlauf and Stoller, one of the last remaining notions shops in the district, told me he knew something was wrong when the sewing operators stopped coming by his store after work. His store sold all the knick-knack parts of clothing—buttons and snaps, hooks and eyes, bias and Velcro, pattern paper, garment bags, and spools of thread. But it was the disappearance of sewing women that had him worried about the changes to come. Sal then noticed all the “middlemen” in the business—the brokers, jobbers, hand-truck pushers, cover-buttoned and buttonhole makers of the district—all the informal proletariats and workforces that once serviced the “formal economy,” had all disappeared.8 Joy, once an employee of his, used to sit in the window of his shop for decades, providing the service of putting on taps and buttons to jeans. But now, even she was gone. Sal then noticed the supply, trim, and notions shops all around him going out of business. After that, the garment sewing factories started closing shop as well. Sal said he knew things were really bad when even the suppliers who supplied him with Velcro and buttons were also going out of business too. He soon realized that his own business had only survived because all of his competitors had folded. “You would think that would make me happy but it did not,” he replied. Sal felt nostalgic for those times when all the sewing operators from the neighborhood factories got off at exactly the same hour and same time each day, pouring into this store on their way home to pick up thread and zippers for the work the next day. “What could be worse,” he said to me, “than sewers not stopping by the store on their way home?” He concluded,

Bill Clinton was a Republican wearing the clothes of a Democrat . .. he had the Republicans drooling. These are the rules that created Enron. NAFTA and GATT—these were the trade organizations that killed us in the Garment District.

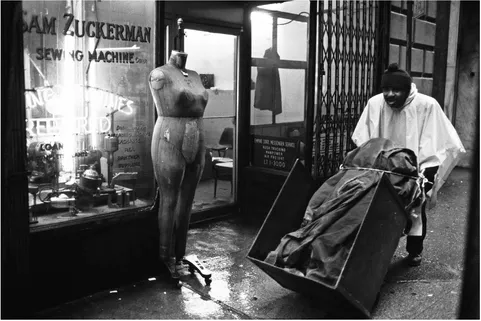

Figure 1.1 The Garment District in Manhattan, West 25th Street

Source: Thomas Hoepker, New York City, 1983.

Source: Thomas Hoepker, New York City, 1983.

Ruth and Larry of Rosen and Chadick noticed the changes in trade laws through the textiles and fabric they sold in their store. Their fathers, who were business partners, established their shop in an industry building on the corner of Seventh Avenue and 40th Street. Ruth and Larry took over the business just when their fathers thought it would go bust.9 The store remains a Garment District institution, with its high ceilings, arched windows, and colors of all kinds from rolls of fabric that reflect off the walls. Ruth explained,

The bridal business was great when we first joined the business in the 1980s. But then, people started importing bridal lace from other countries like China. Suddenly, all the lace wasn’t coming from France but from China, but then sent to places like Haiti for the beading. Then in the 1990s, the fabric stores died out all around us. The import of bridal lace pretty much killed our wedding business.

She noticed that her customer base had changed too. Sewers used to come in off the street to pick out fabrics to make wedding dresses at a time when people actually made their own wedding dresses or hired seamstresses to make them for them. But then people started to buy mass-produced wedding dresses at department stores. The seamstresses stopped coming by, since they had lost their jobs too. Ruth had understood the changing dynamics of the industry and Garment District through the changing origins of lace, the disappearance of sewers, and the rise of mass-produced wedding dresses.

Barry of Barry Martin Fashions told me how the skilled labor needed for design work on leather had also gone away. He pulled out examples of his factory’s leatherwork—a jacket, small purse, wallet, belt—to show me how difficult and labor intensive it was to sew such a simple-looking object. Barry extrapolated, “So, for example, look at this men’s double-breasted leather trench coat. It has to be about 90 square feet with a zipper and lining.” He explained, “You could make that in India for less than $100. But here? It would be at least triple the cost, at $300. That does not even include a profit margin. That’s just for the leather and labor alone.” Barry explained that design had become increasingly more detailed in fashion throughout the 1990s and 2000s. “Look at this tiny wallet for instance. There are so many pieces to it,” he continued. A complicated wallet like the one he showed me could only be done overseas, since it was so labor intensive: “Who is gonna do that here? That’ll take half ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Fashion Workers and the Labor of Design

- 1. Shoddy Seams: The Decline of the New York Garment Industry and Its Transformation Into New York Fashion

- 2. Back of House/Front of House: Creative Skills and "Effortless" Labor Among Samplemakers and Fashion Workers

- 3. The Deskilling of Design: Technology, Education, and the Routinization of Fashion's Engineers

- 4. Designing Diaspora: The Racialization of Labor, the Rebranding of Korea, and the Movement of Fashion Designers Between Seoul and New York

- 5. Fast-Fashion Families: Family Ties and Fast-Fashion Production in the Los Angeles Jobber Market

- 6. Epilogue: Made in China

- Bibliography

- Index