![]()

Part I

ASEAN’s Role in Institutional Developments in Southeast Asia

![]()

1 State Weakness and Political Values

Ramifications for the ASEAN Community

Christopher B.Roberts 1

A large volume of literature has attempted to examine the prospect of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) reaching its goal of establishing an “ASEAN Community” by 2015. However, in much of the IR literature on regionalism, there has been a tendency to “black-box” internal state characteristics. This chapter seeks to redress this flaw by examining how weak states and political values can potentially affect regionalist enterprises. At one level, it explains how state weakness adversely affects regional security and cohesion. Further, the chapter demonstrates that state weakness detracts from both the will and capacity for cooperation and institutionalization in ASEAN. Instead, such conditions generate a preference to respond to the “internal security dilemmas” associated with state weakness through a sovereignty reinforcing model of regional organization – as depicted by ASEAN in its current form. At another level, the chapter examines the nexus between political values and the emergence of foreign policies that promote stronger regionalism in the political and security spheres. The analysis of this second variable is also necessary because it provides some insight about why ASEAN’s rhetorical aspirations (for example, the emergence of an ASEAN Community) continue to be contradicted by ASEAN’s norms together with the patterns of inter-state behavior in Southeast Asia. The chapter concludes that ASEAN will not achieve its goal of an “ASEAN Community” – including political cooperation and integration – as long as it remains constrained by state weakness and divergent political values.

ASEAN’s Aspirations and the Challenge of State Weakness

Through the Bali Concord II (2003), together with the Plan of Action for a Security Community (2004), the Vientiane Plan of Action (2004), the ASEAN Charter (2005), and the ASEAN Blueprint for a Security Community (2009), the ASEAN members have committed to the formation of an “ASEAN Community” by 2015. The ASEAN Community is to be based on three pillars: a “security community,” a “socio-cultural community,” and an “economic community.” According to these instruments, the establishment of the ASEAN Community would lead to greater “integration” and move “political and security cooperation to a higher plane” where the “members shall rely exclusively on peaceful processes in the settlement of differences and disputes.” More specifically, in the course of “achieving a more coherent and clearer path for cooperation” together with “peace, stability, democracy and prosperity in the region,” the ASEAN members have committed to the formation of a “common regional identity,” greater “cohesiveness and harmony” (including a “we-feeling”), the establishment of a “rules-based community,” regional “stability,” “enhanced defence cooperation,” increased “maritime cooperation,” the resolution of “territorial” and “maritime issues,” greater cooperation in tackling “transnational crime” (including “ensuring a drug free ASEAN by 2015”), the “strengthening of law enforcement cooperation,” “the prevention and control of infectious diseases,” the “strengthening of democratic institutions and popular participation,” “strengthening the rule of law and judiciary systems,” “enhancing good governance in public and private sectors,” the “promotion of human rights,” and the establishment of “a single market and production base.” Moreover, ASEAN “subscribes to the principle of comprehensive security [as it] … acknowledge[s] the strong interdependence of the political, economic and social life of the region” (ASEAN Secretariat 2004a). In this context, the ASEAN declarations have also recognized that the three pillars of the ASEAN Community are “closely intertwined and mutually reinforcing for the purpose of ensuring durable peace, stability and shared prosperity in the region” (ASEAN Secretariat 2003).

There is some debate about whether the sum-total of the ASEAN commitments amount to a Deutschian type of a security community such as the European Union (EU). However, the accomplishment of ASEAN’s goals would in fact exceed the requirements for a security community as defined in the scholarly literature. Thus, a set of benchmarks based only on the thresholds set by the ASEAN leaders – namely, a “rules-based community” that will “achieve peace, stability, democracy and prosperity in the region” – will be unlikely to be realized in the absence of an institutionalized ASEAN that has the capacity to guide substantive “political and security cooperation.” Moreover, the evolution of such an organization would, in turn, evidence well-developed levels of trust, interest harmonization, and foreign policy coordination. Regardless of the precise benchmark that is set, this section argues that state weakness significantly impedes the effectiveness of ASEAN, together with the prospects for the establishment of the “ASEAN Community.” According to Sorensen (2007: 365–66), state weakness occurs when there are gaps in any one of the following three spheres: (i) a security gap where the state is unwilling or unable to maintain basic order (protection of the citizens within its territory); (ii) a capacity gap where the state is either unwilling or unable “to provide other basic social values, such as welfare, liberty, and the rule of law”; and (iii) a legitimacy gap “in that the state offers little or nothing, and gets no support in return.” Such weakness impedes regionalist endeavors because it shifts “the focus of security from inter-state lateral pressure toward intra-state, centrifugal challenges – secessionists, terrorists, militias and others” (Kelly 2007: 216). In other words, state weakness generates an internal security dilemma that detracts from, if not trumps, considerations of regional cooperation and integration or an external security dilemma.

In the case of Myanmar, all of Sorenson’s categories apply; for example, the ruling State Peace and Development Committee (SPDC) has not been able to maintain basic order due to the continuation of armed insurgent groups such as the Shan State Army (South). While other insurgent forces may have entered into a ceasefire accords with the Burmese junta, some of these groups have not disarmed as the United Wa State Army (UWSA), for example, continues to maintain a military force of 21,000 soldiers and much of its revenue comes from the manufacture and export of illicit drugs (Roberts 2010: 67, 83–87). Thus, the government cannot even provide safety from crime and neither is there the rule of law or regime legitimacy. In the case of Thailand, the advent of a military coup in 2006, the revival of the insurgency in Southern Thailand, and the violent anti-government protests in May 2010, inter alia, also provides strong indicators of state weakness. Meanwhile, the Philippines, once a symbol of democracy through its “people power movement,” remains plagued by corruption, failed military coups and long running insurgencies in the South. Not only do the Jane’s Intelligence Stability Indicators (Table 1.1) corroborate the weakness of semi-democratic Thailand and the Philippines, but it remains questionable whether they will be able to significantly consolidate their democracies over the short to mid term because of a continued lack of state capacity.

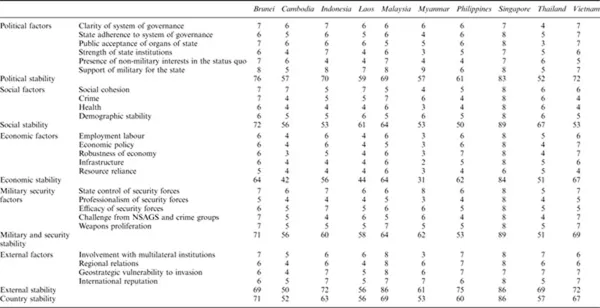

Table 1.1 Jane’s Intelligence Stability Indicators 2010

Note: Janes outlines the methodology behind the rankings in the following manner: Country Stability Ratings provide a quantitative assessment of the stability environment of a country or autonomous territory. All sovereign countries, non-contiguous autonomous territories and de facto independent entities are included in the assessments. To gauge stability, 24 factors (that rely on various objective sub-factors) are rated. The 24 factors are classified within five distinct groupings, namely political, social, economic, external, and military and security. The Country Stability team assesses the stability of each factor as between zero and nine. The various factors are then weighted according to the importance to the particular country’s stability. Stability in each of these groupings is provided, with zero being entirely unstable and 100 stable. The weighted factors are also used to produce an overall territory stability rating, from zero (unstable) to 100 (stable). Finally, the team then assesses global stability levels, so that weighting and ratings are standardized across all regions.

While weak state governments are highly conscious of a need to assert control, they lack the capacity to respond to dissent by means other than violence. As Job (1992: 29) states, these

elites often do not have the resources or the political will to accommodate rival groups; challenges are rather met with increasing repression, “not because it has a high probability of success but because the weakness of the state precludes its resort to less violent alternatives”.

Examples of the type of policy options undertaken by weak states include inciting or promoting internal conflict in the hope of “riding an ethnic or political wave to political and economic gain,” engagement in divide-and-rule tactics, or “siding explicitly or implicitly with one group against another by, for instance, branding members of a group as ‘foreign agents’” (Atzili 2007: 151). Such practices, together with other symptoms of state weakness, were recently evident in Myanmar. In August 2007, mass protests occurred after the SPDC increased the subsidized rate of petrol (gasoline) from USD 1.18 to USD 1.96 per gallon with immediate effect and without any warning (Roberts 2007b). However, on September 26 the government put an end to the unrest when its security forces raided key monasteries and also opened fire on a large demonstration in Yangon (Selth 2008: 379–402). The violent response of the SPDC led to 4,000 arrests and at least 31 deaths including a Japanese photojournalist (Jakarta Post 2007). The international pressure associated with the government’s crackdown generated added pressure against ASEAN for it to take stronger action. Even Barry Desker, Dean of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and an Ambassador for the Singaporean Government, called for Myanmar’s expulsion from the Association (Desker 2007). Moreover, in member-states such as Myanmar, ASEAN’s goal for peace, stability, and comprehensive security remains a distant prospect as anarchy has become domesticated, rendering the risk of intra-state violence and conflict higher (Atzili 2007: 151; Sorensen 2007: 365).

Regardless of the technical definition applied to the “ASEAN Community” and the “ASEAN Security Community,” ASEAN’s declarations of intent prescribe the formation of a regional community of people that are, in the very least, relatively secure. Such “human security” is interdependent with regional security. As Laurie Nathan states:

Domestic instability in the form of large-scale violence precludes the emergence or existence of a security-community in a number of ways. It generates tension and suspicion between states, preventing the forging of trust and common identity. It can also lead to cross-border violence [and in the very least] … other states cannot exclude the possibility of spillover violence in the future and cannot be certain about the reliability of unstable regimes. In the national context, instability seriously undermines the security of citizens and the state. The inhabitants of a country wracked by violence cannot plausibly be said to live in a security-community. A security-community should therefore be defined to include dependable expectations of peaceful domestic change. Based on this definition, structural instability, and authoritarian rule could be viewed as further obstacles to the formation of these communities.

(Nathan 2006: 293)

At the regional level of analysis, both state weakness and an associated insecurity dilemma have also acted to divert valuable resources away from regionalist endeavors. A prime example occurred in Indonesia where it had acted as the natural leader or “first among equals” in ASEAN. However, following the collapse of Suharto’s New Order regime, there was a palpable absence of Indonesian leadership until its security community proposal in 2003 (Acharya 2009a: 259). Thus, the historical record supports some of the contentions of the “new regionalism” literature where Fawcett (2005: 72), for example, argues that a low state capacity is also “an impediment to cooperation, and will, along with the nature of the regional and international environment, crucially affect the success or failure of any regionalist project.” State weakness also challenges both regional cohesion and security. In connection with the 2007 protests in Myanmar, for example, international pressure for ASEAN to take stronger action – including a US Senate Resolution calling on the Association to expel, or at least suspend Myanmar from ASEAN membership – represented a direct challenge to the ASEAN Way including the principles of respect for sovereignty and non-interference in each other’s internal affairs (Rahim 2008: 72). The subsequent role of the relatively more democratic and/or globalized members – for example Singapore and Indonesia – in pressuring the SPDC through joint ASEAN statements (and other means), challenged regional cohesion vis-à-vis the more authoritarian members who continue to uphold the central tenets of the “ASEAN Way,” namely: sovereignty, non-interference, and consensus based decision-making (Roberts 2010: 141–64). In terms of regional security, the inability of the SPDC to enforce positive sovereignty has also meant that an estimated 80 percent of illicit drugs in Thailand now come from Myanmar and this had led to hundreds of thousands, even millions, of drug addicts and users in the country (Katanyuu 2006: 828; Department of Justice 2003).

Both Ayoob and Job suggest that because many weak states are in the “early process of nation-building” there is a subsequent “stress on the domestic, rather than international, use of force” (Kelly 2007: 217). Consequently, “most third world states do not seek conquest of their neighbors, but rather their cooperation” (Kelly 2007: 217). While these behavioral trends have at times been evident on the surface of ASEAN’s relations, there remains a high risk of competitive behavior and some risk of limited armed conflict. This is because both weak and/or undemocratic states are typically less willing to sacrifice “self-interests” for the collective good; moreover, such tendencies are compounded by relatively low levels of integration in the political, security, and economic spheres. Further, associated weaknesses in regime legitimacy exacerbate the probability of a state alienating a neighbor during times of political crisis (Atzili 2007: 150). An example of this occurred in 2008 in relation to a territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over the Preah Vihear temple. Both Thailand’s Prime Minister and Foreign Minister had indicated to Cambodia that their government would accept a decision by the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation to list the temple as a World Heritage site (Osborne 2009). However, domestic opponents believed that the leaders of the Thai Government were acting as proxies for ousted Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and this resulted in a crisis of legitimacy for the Thai Government. Thailand’s leaders responded to their weak legitimacy by exploiting nationalist sentiments for domestic political gain. In the process, Thailand sacrificed positive relations with Cambodia and the resulting chaos led to several armed skirmishes and the death of between 12 and 18 Thai and Khmer soldiers (So 2009). Had there been “greater state coherence” then it would have been “more difficult for pan-nationalist ideologies to penetrate the state and to challenge pragmatic policies” (Miller 2005: 244).

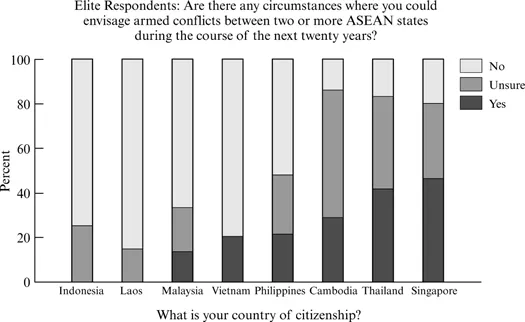

Attempts to compensate for weak regime legitimacy by emphasizing a common threat or enemy have also been relatively common practices in Southeast Asia more generally. For Thailand, it was the Burmese; for Singapore, it was Malaysia and, at times, Indonesia; and for Indonesia, it was either the Chinese or the Federation of Malaysia (Turnbull 2005: 285). However, the consequences of such practices continue to affect the region today. Thus, in the wake of a 2005 territorial dispute between Indonesia and Malaysia concerning the Ambalat offshore oil block, a crowd of Indonesians gathered outside the Malaysian embassy in Jakarta shouting “crush Malaysia” – a catchphrase from President Sukarno’s Konfrontasi policy decades earlier (Emmerson 2005: 175). Such historical animosities – combined with diversity in the cultural, ethnic, religious, and economic spheres – continue to effect regional relations in other respects. In a survey of 100 elites from all ten of the ASEAN nations, 59.8 percent of the respondents indicated that they could not “trust their neighbors to be good neighbors.” Further, when the elite respondents were asked if there were any circumstances where they could envision armed conflict between two or more ASEAN states (Figure 1.1), half the respondents answered “no” but the other half indicated either “yes” (22.3 percent) or that they were “unsure” (26.7 percent). Here it is interesting to note that the “risk of conflict” was perceived as particularly high in Cambodia (29 percent), Thailand (42 percent), and Singapore (47 percent) (Roberts 2007a: 87–88). The limited levels of trust indicated by the elite-level respondents is particularly problematic for the ASEAN proposals as different states will be more hesitant to enter into cooperative arrangements – particularly in relation to key political and security issues – in the absence of adequate trust (Kegley and Raymond 1990: 152).

Figure 1.1 Southeast Asian Elite Threat Perceptions.

Because of the dynamics behind state weakness, regional organizations such as ASEAN are best viewed as “mutual sovereignty reinforcement coalitions, not integrationist regional bodies like the European Union” (Kelly 2007: 218). This contention is compatible with the analysis of Ayoob (1995: 13) who suggests regions populated by weak states are structurally different from the strong state systems of the North West. This analogy also applies to the structure of regional organizations that embrace weak-state systems. However, rather than these structural differences being explained by “Asian values” or other socio-cultural factors, organizations such as ASEAN remain under-institutionalized because they primarily “exist for tacit elite collaboration to quell their common intrastate challenges” (Kelly 2007: 218). Such insights coincide with the area studies specialists of Southeast Asia. For example, Collins (2003: 141) suggests that the principles of the ASEAN Way effectively provide for (i) the avoidance of public criticism; and (ii) the provision of support “if an elite is threatened by internal rebellion.” Thus, Funston (1998: 27) argues that the idea of helping neighboring governments and “acting as a mutual support group … is very much the essence of ASEAN.” While the previous paragraphs have noted some significant caveats in connection with how much one can depend on assistance through this “mutual support group” (for example, the Cambodia–Thailand dispute), the long term effect of a sovereignty reinforcing model of regional organization is that it has very little positive impact on the level of state capacity (or, in turn, regional cooperation) as it provides few incentives to adopt the reforms necessary for internal consolidation – such as parliamentary and security sector reform or the adoption of more inclusionary nation-building practices and policies (Atzili 2007: 140).

Adequate state capacity is also a key enabler for the consolidation of a liberal democracy. As the next section will examine, the presence of stable democratic governments may aid regionalist endeavors – including associated increases to the level of cooperation and integration – but an ...